The stun gun jolt left Chinedu Okobi writhing on his back in the crosswalk of a busy Millbrae street.

“What’d I do?” Okobi asked, raising his hands into the air.

Five deputies from the San Mateo County Sheriff’s Office hovered around him, one of them zapping Okobi with a yellow Taser.

“I’m lost,” he said. “Spread the word of God.”

What began that day in October 2018 as a jaywalking stop led to Okobi getting tased, dogpiled and left slumped on a deputy’s leg.

Okobi, a 36-year-old Black man who struggled with mental illness, died from “cardiac arrest following physical exertion, physical restraint, and recent electro-muscular disruption,” an autopsy later determined (opens in new tab).

His death was among a spate of fatal encounters that year after officers from various agencies in San Mateo County shocked people with Tasers. It was also the tipping point for the county sheriff to limit how many times a deputy can tase a suspect to three.

Some four years later, Okobi’s family quietly settled a lawsuit over his death for a massive $4.5 million sum, according to records obtained by The Standard. It appears to be the county’s largest payout for a police misconduct claim in at least five years.

The Standard unearthed the settlement through a public records request as the deaths of Tyre Nichols in Memphis and Keenan Anderson in Los Angeles renewed national outcry (opens in new tab) over police violence. Not unlike Okobi, Anderson died last month after an officer tased him repeatedly.

Okobi’s sister, Ebele Okobi, finds it difficult to keep up with the details of the latest police killings—it’s hard to grapple with all the violence. Even before her brother died, she left the country because she wanted to raise her son somewhere safer for a Black boy than the U.S.

Ebele Okobi said her brother’s death reflects the violence of American policing, and why officers should not have Tasers.

“Other countries around the world have figured out how to create peaceful environments without policemen being armed to the teeth,” she said. “The way that America does policing is dangerous.”

The deputy who stunned Okobi should not have shocked him as many times as he did as quickly as he did, the family’s attorney Adanté Pointer said.

“They should learn that the Taser is not a toy—it is, in fact, a potentially deadly weapon when used inappropriately or incorrectly,” Pointer said. “They have to be just as careful in using a Taser as they are in using their firearm or gun.”

But Ed Obayashi, a use-of-force expert and Plumas County deputy sheriff who reviewed video of the encounter when asked by The Standard, said the case illustrates a dilemma law enforcement has yet to resolve.

If officers use batons against a resistant suspect, that could look like the Rodney King beating. Swarming and dogpiling a suspect can cause them to die by not being able to breath beneath the weight of the officers.

“What are the officers supposed to do?” Obayashi said. “My solution is, if you want us to let people just walk away, fine, let them walk.”

While he could not determine whether the use of force was justified without more information, Obayashi said Anderson did not appear to resist Los Angeles police nearly as much as Okobi in San Mateo County did.

The San Mateo County Sheriff’s Office and County Counsel’s Office each declined to comment on the settlement.

Attorneys for the county argued the force was justified because Okobi resisted deputies and endangered drivers.

“Short of letting Okobi run freely in highway traffic,” they wrote in court filings, “the deputies did everything that they reasonably could to try and detain Okobi safely—while keeping themselves and those on the road safe.”

A Fatal Crossing

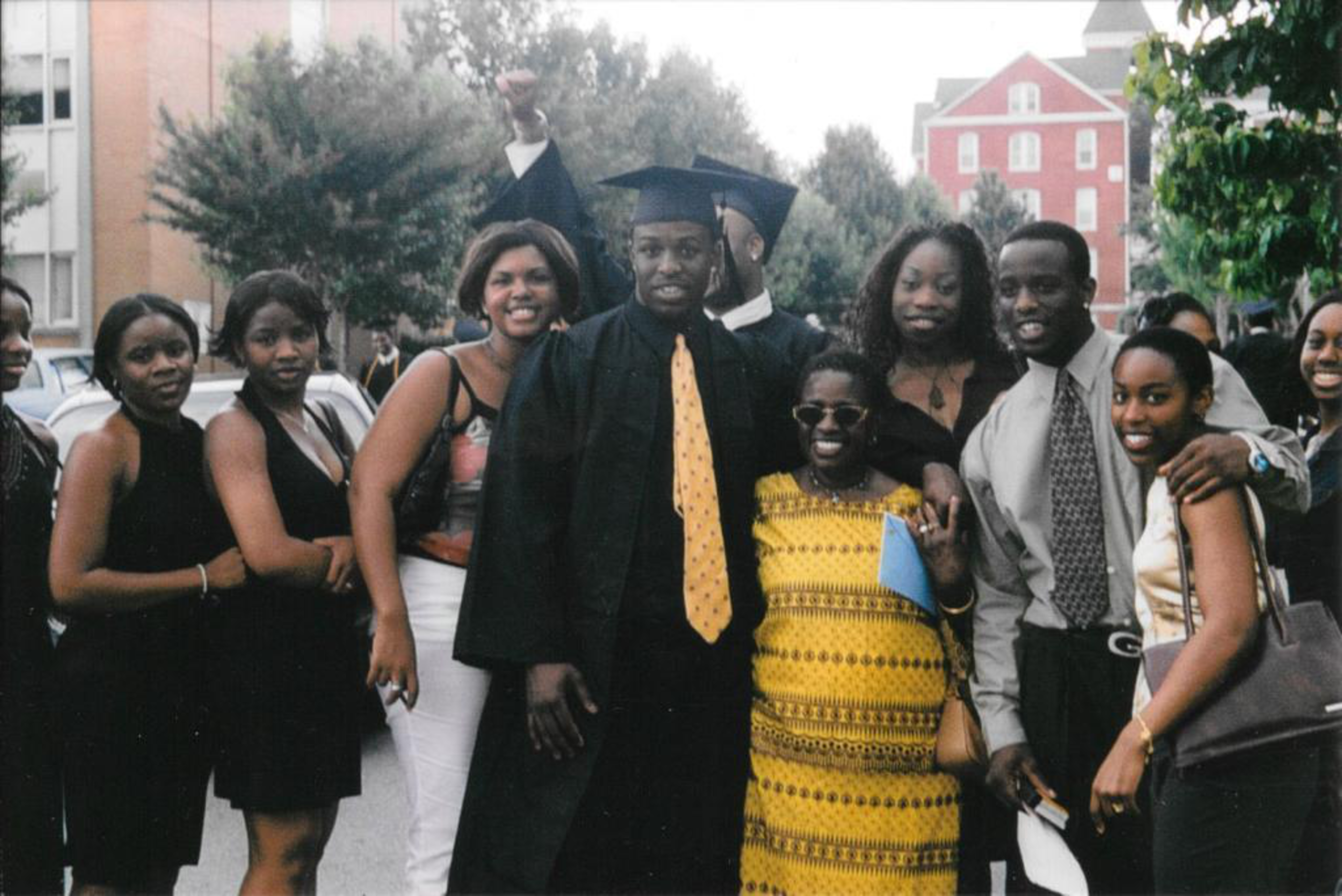

Okobi grew up in San Francisco’s Diamond Heights and went on to graduate from Morehouse College, where he studied business, according to his sister.

In his early 20s, Okobi began experiencing symptoms of mental illness and returned to California instead of going to graduate school.

His sister said Okobi held down a job at Home Depot and lived a full life in the years that followed. But he began falling out of touch in the time leading up to his death.

She said he may have stopped taking his medication and may not have had a place to stay after breaking up with a woman he lived with.

On Oct. 3, 2018, Okobi was walking across El Camino Real with a bag in hand when a deputy named Joshua Wang spotted him.

Video shows Okobi crossing the street against a light (opens in new tab), before Wang pulled up in a police cruiser and tried to stop him for jaywalking.

Okobi pulled away when deputies confronted him on the sidewalk, fell when Wang began tasing him and then tried to run away, the video shows.

He punched Wang in the face after the deputy tried to hit him with a baton, authorities said.

The deputies then swarmed Okobi and piled on top of him.

In all, Wang used the Taser on Okobi seven times, although there was a dispute in court over how many times he was actually shocked.

San Mateo County District Attorney Steve Wagstaffe declined to charge Wang (opens in new tab) or the other deputies at the scene.

Okobi’s family said the settlement won’t bring them justice, but they plan to use the seven-figure payout for good.

Most of the money will go to his young daughter, while his mother plans to use all of her portion to start a fund to support people trying to advance racial justice.

It will be called the “Valentine Fund” after Okobi, who was born Feb. 13.

“His middle name is Valentine,” Ebele Okobi explained. “He was all about love.”