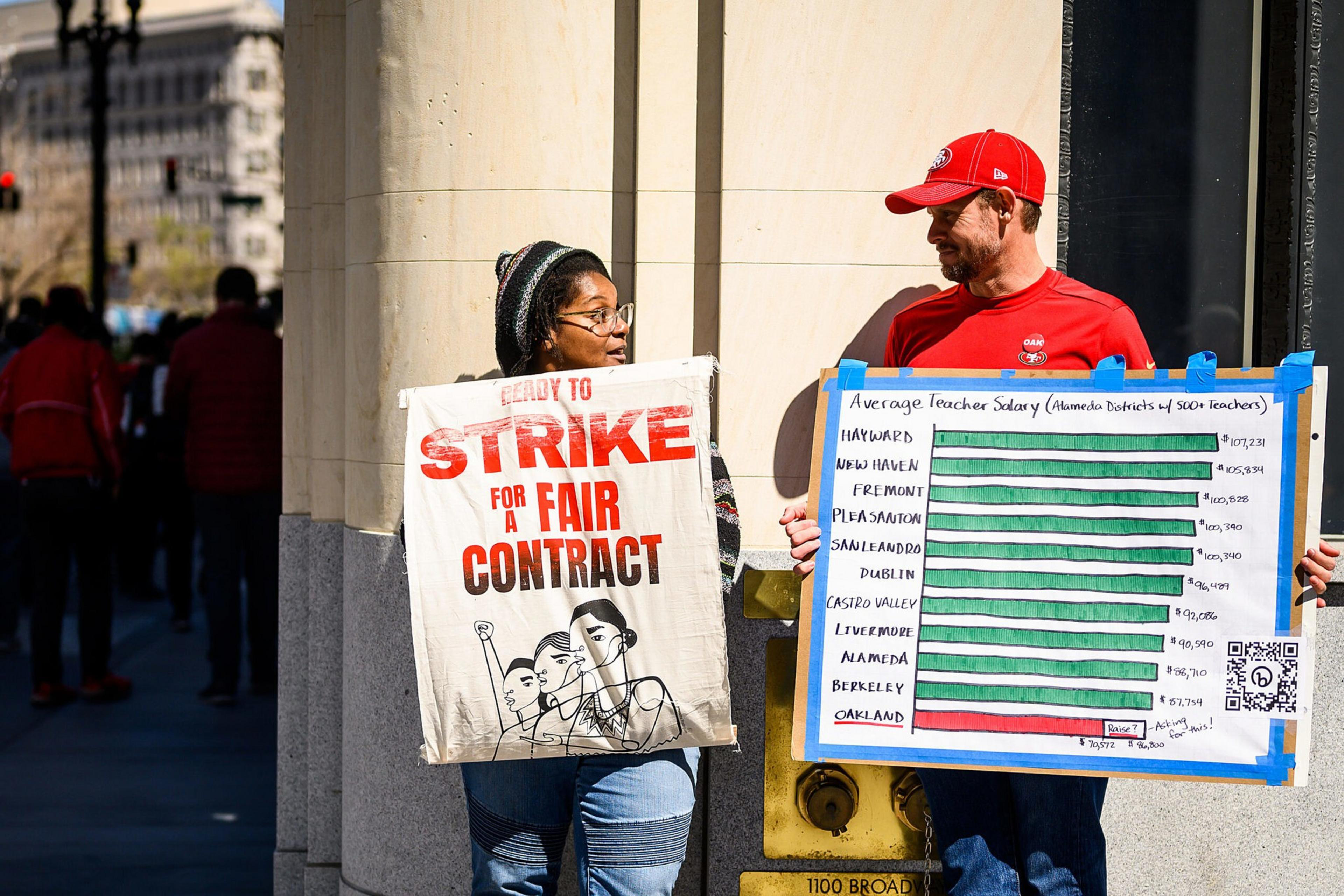

For the second year in a row, Oakland teachers have called a strike over pay and school conditions amid teacher vacancies.

The Oakland Education Association has been without a labor contract and in negotiations with the Oakland Unified School District since November. Unless an agreement is reached, some 2,500 teachers will go on strike starting Thursday.

“Strikes take a lot of organizing and time and energy,” Amara Schoenberg, a teacher in Oakland on the union’s bargaining committee, said before the strike was announced. “It feels like when you’re in this stuck place, there’s nothing more you can do except stop working to make sure they’re hearing us. Unfortunately, we’re in a place in our union where we have a lot of mistrust in our district.”

They’re not the only ones. With a pandemic, steep staffing shortages and a rising cost of living, teachers up and down the state have reached a tipping point.

Since the massive 2012 strike by Chicago teachers (opens in new tab) that made international headlines and received broad public support, strikes in public education nationwide have become more common, said Ken Jacobs, chair of the UC Berkeley Labor Center.

“Teachers had been reluctant to strike historically, over not wanting to negatively affect children’s education,” Jacobs said. “I think what turned around after the Chicago teachers’ strike was this recognition that while striking can cause real problems in the short term, in the long term, […] those strikes may be what’s needed to have strong public education.”

California’s educators seem to have gotten the memo. Teachers in Los Angeles backed a three-day strike by support staff (opens in new tab) that shut down schools in March. In Marin County, the San Rafael Teachers Association has been stuck in negotiations since November and nearly all members authorized a strike in a March 31 vote. In February, a strike was averted among West Contra Costa Unified School District teachers after the local educators’ union—armed with a strike vote approved by nearly all its members—reached an agreement with officials.

This week’s action isn’t even the only episode of labor unrest in the East Bay’s biggest school district. Oakland teachers went on a one-day strike in April 2022 over school closures (opens in new tab), in addition to a weeklong strike in 2019 (opens in new tab) over pay increases in their last contract.

San Francisco teachers, meanwhile, haven’t gone on strike since 1979 (opens in new tab). The last time they voted to authorize a strike was in 2014, coming close again in 2017 (opens in new tab). Two votes by members are required for the United Educators of San Francisco to go on strike.

Could this year be different? Like their peers in Oakland, San Francisco educators must deal with numerous vacancies and greater student behavioral problems that emerged during the pandemic. On top of that, staff have contended with faulty paychecks that still have the district in crisis mode (opens in new tab) more than a year later.

The United Educators of San Francisco have been without a fully new contract since 2017 and began negotiations this spring. Some teachers already feel there has not been enough progress to match the urgency.

“It’s clear the district is not taking it seriously or they just don’t have the capacity and that’s just not acceptable,” said Frank Lara, SF teachers’ union vice president. “We’re definitely looking to escalate, but there are many steps.”

Frustrated by the response to contract negotiations, San Francisco teachers are ramping up the pickets at more than 50 schools this week in the morning, after school and even drawing the attention of passersby during lunch periods.

“The district absolutely takes labor negotiations seriously,” spokesperson Laura Dudnick said in an email. “While our efforts may not always be seen, the district works hard to provide employees with the support they want, given the many complex circumstances.”

José Montenegro, a teacher at Balboa High School with the San Francisco Movement of Rank-and-File Educators, a group of union members not in leadership, noted that Oakland educators have likely been pushed to escalate tactics by austerity from a state takeover and subsequent school closures, plus the proliferation of charter schools.

San Francisco voters have also approved ballot measures to fund pay increases and arts education and, most recently, to redirect property taxes to beef up school services and student academic achievement.

But working conditions have declined in both school districts, Montenegro said. He attributed the extended period without a San Francisco teachers’ strike to a historically collaborative approach between union leaders and the district.

“I think we would see a similar thing here in San Francisco because of the working conditions,” Montenegro said. “In reality, the way we see it, this is a class struggle between the workers and the bosses. The only way they’re going to concede to our demands is if we put up a fight and strike.”