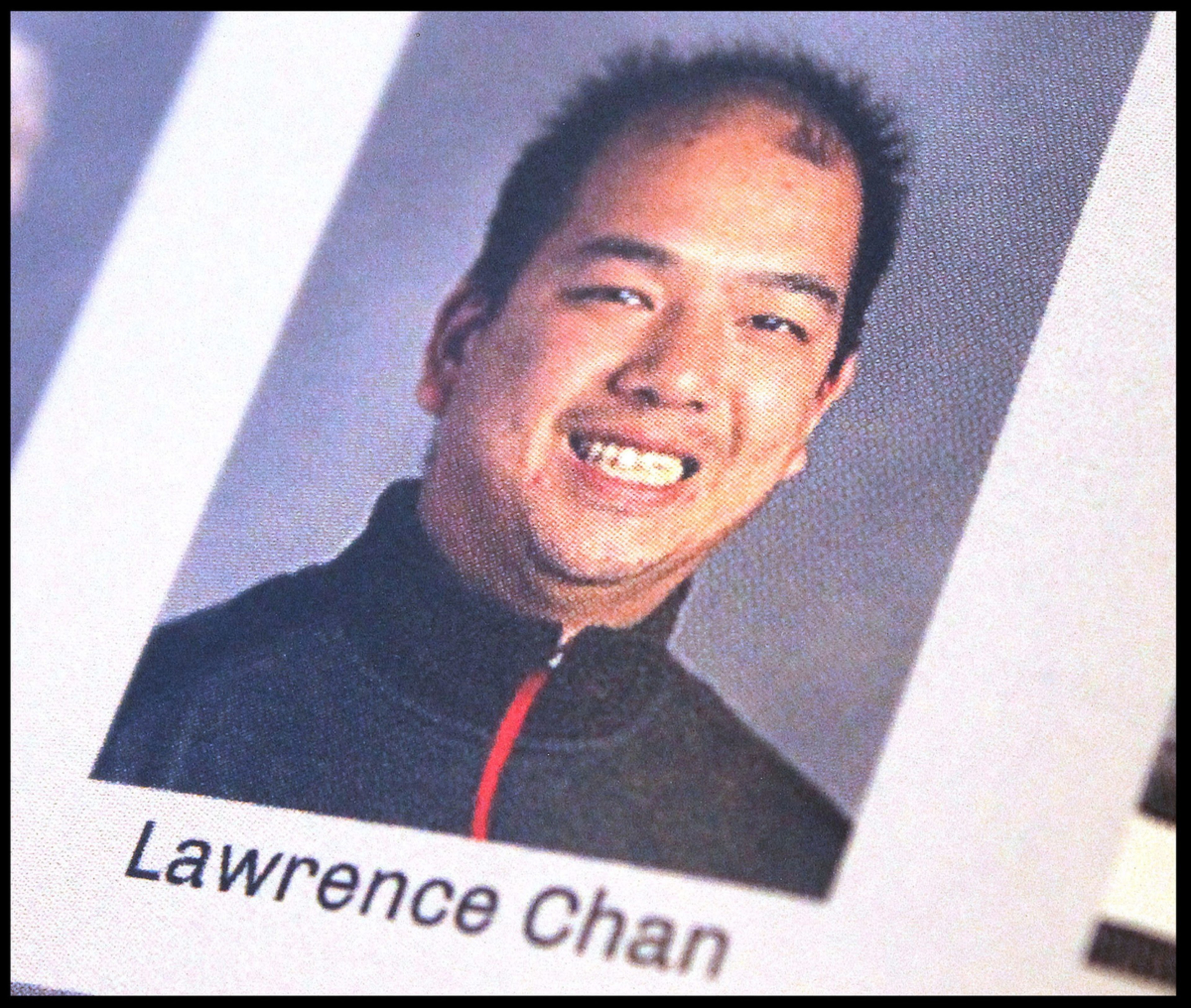

The athletic director repeatedly called the teenage girl out of class and then escorted her to a locker room, a lawsuit alleges. Later, he would send her back to her class at George Washington High School, a routine that at least one teacher found odd.

These were not legitimate hall passes, but instead repeated episodes of alleged sexual abuse that went on for four years, according to the lawsuit against the San Francisco Unified School District. The girl eventually confided in her college guidance counselor, who called the police. Officials then put Lawrence Young-Yet Chan on leave, the lawsuit said.

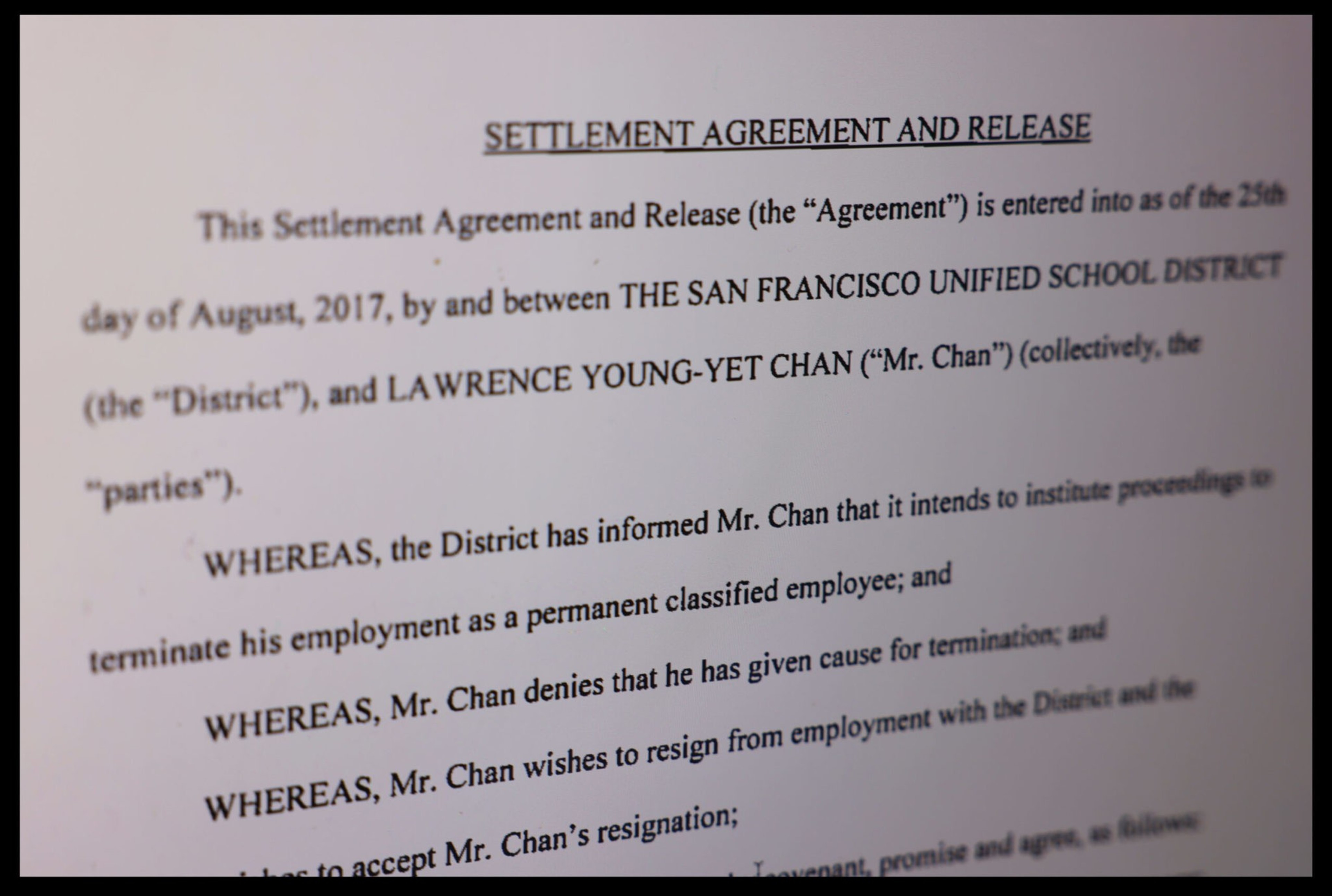

But then Chan was allowed to quietly resign.

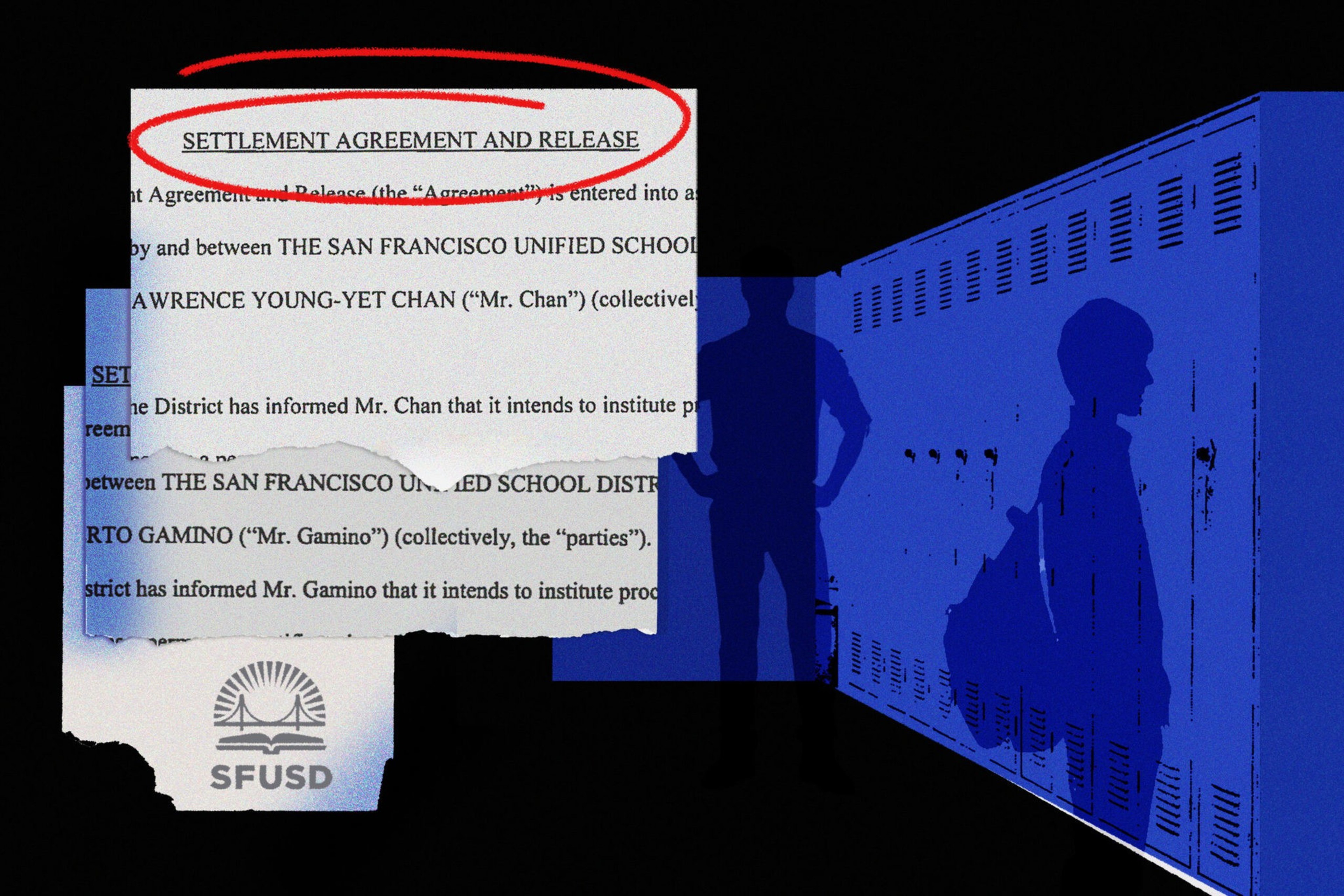

He wasn’t the only one. Public records obtained by The Standard reveal that, since 2017, at least 19 employees of San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) who were accused of sexual misconduct were allowed to resign or retire in lieu of termination. As with some other cases that resulted in agreements to resign, The Standard found no evidence that Chan had been charged with a crime.

The practice of handling sexual misconduct allegations out of public view is more commonplace than widely understood. But experts say these types of quiet settlement agreements allow abuse to persist.

Federal watchdogs, victim advocates and even former administrators of San Francisco schools say it’s a bad idea to let an accused abuser quietly walk away and that a full investigation of these incidents would help better protect the safety of all students.

But for officials tasked with solving the institutional problems that come with abuse allegations, the practice appears difficult to resist. A quiet agreement that has the alleged abuser simply resign eliminates the need to invest time and expense honoring holding a hearing, weighing appeals and other stipulations guaranteed in union contracts.

That can be a big deal: A 2010 federal study (opens in new tab) reported that a school administrator feared it could cost up to $100,000 to fire a teacher—“even with a slam-dunk case”—because investigations, hearings, appeals and other required steps that precede a dismissal take time and require the attention of senior staff. Accommodating an accused abuser with a separation agreement can discreetly curtail what could have been a drawn-out embarrassment for the institution, experts say.

The so-called release agreement also protects students and staff from having to repeatedly recount traumatic experiences, according to a statement from the district. Administrators “take every step to investigate and respond to the matter within the scope of our jurisdiction,” the statement reads.

‘Passing the Trash’

Agreeing to allow a school staffer to simply resign also quickly distances an accused individual from students. San Francisco schools have repeatedly employed this short-term solution to sexual misconduct allegations.

Multiple government investigations, meanwhile, reveal that schools nationwide have repeatedly kept alleged employee misconduct under wraps and that, in some cases, these teachers have gone on to prey on more students.

Union contracts require keeping a school employee on staff during a pending dismissal, but not necessarily on-premises. The employee has a right to a hearing with testimony from witnesses, potentially including students who have been abused or harassed.

Chan and other accused San Francisco school employees agreed not to sue or apply for another job at a San Francisco public school as part of their separation agreements, thus avoiding proceedings that could have ended with a dismissal.

Critics, however, describe the downsides to permitting schools to forgo fact-finding.

“Every complaint needs to have a prompt, thorough investigation,” said Billie-Jo Grant, a member of the board of directors of Stop Educator Sexual Abuse, Misconduct and Exploitation. “It protects student safety—not only for that student, but also for all students.”

Letting bad teachers resign and possibly reappear at other schools is common enough nationwide that it has its own name in education circles: “passing the trash (opens in new tab).”

“The long-term consequence is that this person doesn’t have a record, and there’s no [official] evidence of wrongdoing,” said Grant. This creates a risk that the employee can “go get hired somewhere else, and they do it again.”

The Standard obtained copies of settlement agreements from San Francisco schools following public records requests.

Of the 19 misconduct-related settlement agreements, five involved alleged inappropriate sexual contact with students.

In one 2019 case, a 6-year-old allegedly told their mother that a teacher had them sit on his lap while he touched their private parts. School officials found the allegation credible, even though a meeting with police did not result in charges being filed, according to personnel records. School officials were prepared to proceed with termination, but the teacher sought retirement in lieu of defending himself.

Some offenses did not involve touching students. A Lowell High School math teacher allegedly told an off-color story about his teenage sexual escapades in class. He also commented on a female student’s clothing as being “sexually suggestive” and said the attire was “distracting the class,” according to his personnel file. He was allowed to retire. Others settlements related to sexual harassment against other staff members, sometimes in the presence of students.

But in seven of the cases, school officials did not provide information about what the employees were accused of. There is no clear way for the public to find out what led these individuals to resign.

Hidden Misconduct

The allegations that led to Chan’s settlement only came to light after the alleged victim filed a civil suit against San Francisco schools in August. A second woman with similar allegations soon came forward to join the suit.

The first former student said in the lawsuit that Chan sexually assaulted her in the locker room, in the gym’s stairwell, in the student government classroom and in his office behind a locked door and a covered window.

Nonetheless, Chan was allowed to settle.

On Feb. 3, a judge rejected a request by San Francisco schools to throw out allegations that Chan’s bosses should have been aware that he was grooming female students, saying the court needs to weigh these claims.

After the allegations against Chan came to light, San Francisco “immediately launched an investigation and placed the employee on leave,” according to an email from a school spokesperson. “Throughout the investigation, the [school] district fully cooperated with law enforcement.”

Several attempts to reach Chan through associated phone numbers, emails and his lawyer at the time of the settlement were unsuccessful.

In 2017, the same year Chan resigned, San Francisco also allowed Roberto Gamino, a physical education teacher and soccer coach at John O’Connell High School, to retire under a settlement agreement.

An investigation by San Francisco schools found that 30 female students made complaints about Gamino. The gym teacher made inappropriate comments about their appearances, and touched them and hugged them in a manner that made them uncomfortable, according to findings described in a report to the state teacher credentialing organization.

In at least three cases, Gamino allegedly engaged in “explicitly assaultive conduct”: grabbing, pinning and groping female students, the document stated. The school had received reports of his alleged inappropriate behavior two years earlier.

A woman who answered the phone and identified herself as Gamino’s wife did not provide contact information, saying he was out of the country and no longer had an email address.

Lauren Cerri, a lawyer who represents both of Chan’s alleged victims, calls the situation with settlement agreements disturbing.

The settlement is “protecting the image and reputation of the school and the [school] district over the safety of children from lifelong harm,” she opined.

Balancing Act

By law, teachers and school employees are required to report suspected child abuse to law enforcement. Both California and the San Francisco schools have policies for preventing and addressing misconduct.

But that doesn’t always mean schools handle misconduct allegations properly.

A 2016 civil complaint alleged that the principal of Leola M. Havard Early Education School in the Bayview neighborhood witnessed a teacher’s aide holding a 5-year-old student on his lap and “thrusting him.” But instead of calling the police, she only reported the incident to school officials, allegedly telling the boy’s father that because she’d fired the aide, it was not necessary to bring in law enforcement, the complaint said.

In the case of Chan, one teacher had reportedly found it odd that he was frequently calling a student out of class. But the teacher “allowed it to happen and took no action to report it,” according to the lawsuit.

Such situations aren’t unique to San Francisco.

Irwin Zalkin, a lawyer representing abuse victims, says administrators can be loath to turn in valued colleagues.

“They tend to be dismissive of complaints,” he said.

Federal watchdogs have for years been calling out deals like San Francisco’s.

The Government Accountability Office (opens in new tab) reported in 2010 that these deals allow teachers to claim they have never been fired from a school so they can get another job with children. The U.S. Department of Justice in 2017 quoted administrators saying they allowed accused teachers to resign quietly (opens in new tab) in order to keep parents or news reporters from discovering abuse. The U.S. Department of Education (opens in new tab)produced a report in 2022 quoting an educator who was ashamed of the practice.

“There are plenty of times you will look into someone, and you’ve got probable cause to believe there was sexual misconduct,” the report quoted them as saying. “But for whatever reason, maybe you let them resign instead of being fired. That happens a lot.”

Former top San Francisco school officials shared similar laments.

David Campos, who served as general counsel for San Francisco schools from 2004 to 2007, was aware of the practice but said he found it unsavory. “I certainly would feel uncomfortable recommending a settlement,” he said.

Jill Wynns, who served on the Board of Education from 1993 until 2017, said officials sometimes heard allegations for which there was no proof.

“The best thing we could do was try to get [the teacher] to surrender their credential,” she said.

Cal Kinoshita, a student delegate to the San Francisco Board of Education and an activist against sexual assault, believes the settlements are shortsighted.

“It seems sort of irresponsible and is counterproductive to the mission of protecting students and children to just pawn off problem teachers to other districts without giving them knowledge of the behavior,” he said.