In middle school, Jimmy Orellana Castillo felt like no one expected much of him—and his grades came to reflect that.

So when the pandemic struck during his freshman year at Independence High School, it disrupted his already tenuous academic career. He went from hardly focusing in the classroom to hardly logging on at home. With school becoming less and less engaging, he began spending more time making a buck by working construction gigs like installing flooring.

“Sometimes I wouldn’t even go to the class,” Orellana Castillo said. “It was just easier not to. If you don’t got no motivation, no one’s pushing you […] I wasn’t really feeling it.”

He was far from alone.

Chronic absenteeism (opens in new tab) in the San Francisco Unified School District has more than doubled from pre-pandemic levels, rising from 14% to 28%, according to preliminary data for 2021-22. A student is considered chronically absent when they miss 10% of the 180-day school year.

The impacts have fallen unevenly across San Francisco, with the highest concentrations of students repeatedly skipping class happening in the southeastern parts of the city.

Malcolm X Academy Elementary School in the Bayview reported 89% of students as chronically absent this past school year compared with 42% in 2018-19 (opens in new tab). Cesar Chavez Elementary School in the Mission District hit 70%, compared with 29% in the same period.

Pacific Islanders recorded the highest rates of chronic absenteeism this past school year, at 69% districtwide. Black students were close, with 64% marked chronically absent, with American Indians at 58% and Latinos at 47%.

Nearly 30% of Filipino students were chronically absent in the same period, compared to 20% of white students and just 9% of their Asian counterparts (opens in new tab).

Meanwhile, some of the district’s traditional measures of combating the issue, like the use of an attendance-review board, have lapsed since the pandemic with no indication of it resuming.

SFUSD, which counts just under 50,000 students and 130 schools under its purview, is no outlier. Nationwide, 72% of public schools reported an increase in chronic absenteeism, the U.S. Department of Education revealed in July (opens in new tab). The rates exploded during a school year full of challenges, including remote learning, quarantines and financial precarity for millions of American families.

Though the recent uptick has been fueled by the pandemic, experts say it’s also a reflection of more long-standing problems, from poor transportation options to a lack of social support for families struggling to get by in one of the most expensive cities in the nation.

Now, as schools get to a new normal, SFUSD has signaled more focus on student outcomes after a contentious recall. But none of that matters without students attending class.

In addition to learning loss, absenteeism takes a financial toll on districts as well because of how the state ties attendance to school funding. The California Department of Education will release updated data on attendance and absenteeism in early-to-mid December, spokesperson Scott Roark said.

“We absolutely know that if we don’t address chronic absenteeism, then we will not make the progress we need to in student achievement and student outcomes,” Board of Education President Jenny Lam told The Standard. “Frankly, chronic absenteeism is a symptom. It is one symptom of what can be causing students not being engaged in learning, their abilities to be at school consistently, and that is going to impact their learning and those outcomes.”

‘It Doesn’t Take One Person’

Hedy Chang, founder and executive director of the nonprofit Attendance Works, said kids go to school when they feel healthy and safe, academically engaged and when they have support from adults and peers.

“A lot of those positive conditions for learning have been eroded,” Chang said. “With all the teacher and staff turnover, that sense of belonging, connection and support has really been challenged.”

Chang divided the reasons students don’t show up into several buckets: barriers, aversion, lack of engagement and misconceptions.

Unstable housing, inadequate transportation and unsafe passage are all barriers that loom over schooling. What happens in school could push children away, from problematic or racialized discipline to bullying. Students may not feel pulled into school with the right relationships to adults and peers, or they might lack academic support. And some parents may not understand how absences add up even if they’re excused, which opens up potential for the Office of the District Attorney to become involved, if serious enough.

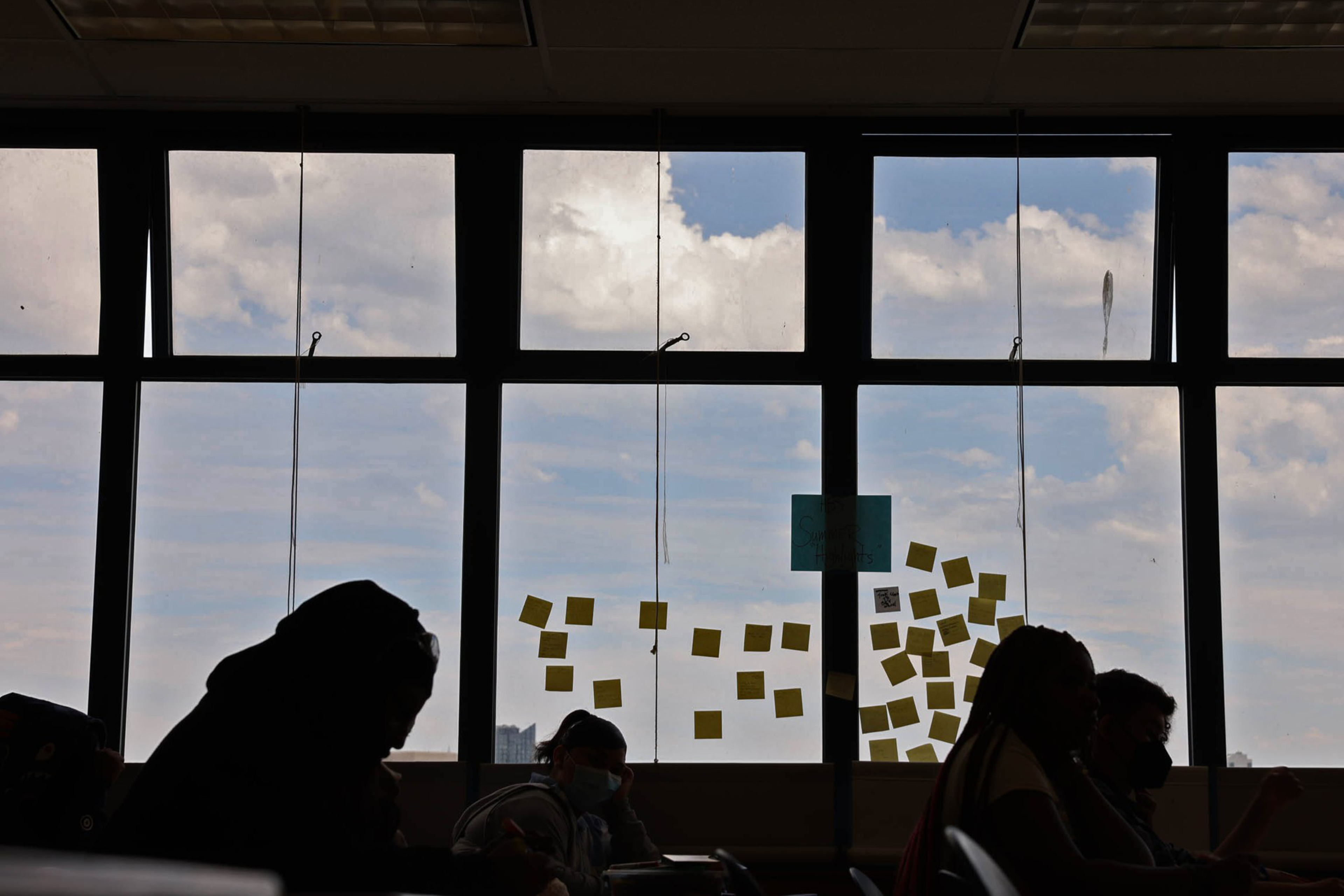

Recent data from an annual SFUSD survey demonstrates how the pandemic affected student views on school climate. Feelings of safety have declined, dropping from 76% safety favorability in 2020-21 to just 65% in 2021-22. That may suggest students feel less safe and supported on campus than at home.

Teanna Tillery, an officer for teachers union United Educators of San Francisco, worked in absenteeism prevention for about 20 years. She emphasized the role of mental health—for students and their guardians—on attendance. Anxiety and depression are a big barrier for middle and high school students, while caregivers could be struggling with their own mental health issues or substance abuse.

“Families have to navigate through everyday life,” Tillery said. “Sometimes it’s just very hard. Once we’re able to get in front of a family and allow them to share their story and for us to collectively come up with a plan […] they tend to open up. There’s just not enough of it happening.”

SFUSD saw the greatest dips in attendance during the Covid-19 surges in September 2021 and January this year, district spokesperson Laura Dudnick said. This was before SFUSD implemented group tracing, allowing students who were close contacts of Covid-positive school members to stay in school and tests unless symptoms emerged.

Tenderloin Community School was one of the schools that felt the impact of Covid surges. Preliminary data shows that 60% of its students were chronically absent during the 2021-22 school year. The school uses a portal for family communication to report daily attendance rates and remind parents to schedule any appointments outside of school hours.

“We also recognize that prior to group tracing, there were times when entire classes were absent due to Covid exposures and illnesses,” Principal Paul Lister said. “This happened multiple times throughout the school year, and we know this impacted our attendance rates.”

At the elementary-school level, it can simply be a matter of habit.

Attendance liaison Ariana Velasco previously worked through the district’s central office and is now at John Muir Elementary School, which struggled with absenteeism when she was stationed there in 2014-16. She got creative with rewards for students to show up on time and daily, allowing them to buy toys and other knick-knacks with the stars that they earned.

The rates improved 14%, according to Velasco, who is trying to find funds to bring back the initiative. In the 2021-22 school year, 59% of its students were chronically absent.

“The most important thing is always meeting families where they’re at and building up the capacity to where they can attend daily,” said Velsaco, who has specialized in attendance in the district since 2007. “We need to make sure students have good habits so they don’t drop out, they don’t get into problems because they’re engaged.”

Until she went back to John Muir, Velasco was one of five child welfare and attendance liaisons. Pre-pandemic, she estimates there were seven or eight of them in the district.

SFUSD also has not yet brought back the Student Attendance Review Board, a district entity authorized by state law to escalate cases after options have been exhausted on the campus level, according to Tillery and Velasco. After repeated attempts, the district would not confirm its staffing levels of attendance liaisons or indicate why SARB has not yet resumed.

Instead, spokesperson Laura Dudnick said attendance is primarily handled at the school level and the district advises scheduling family meetings after six unexcused absences. The families may be connected to outside community organizations or resources.

SFUSD, Dudnick added, is “in the process of introducing new systems of support for school staff to support students in attending school.” Currently, schools may reach out to the Student Family School Resource Link for general consultation, or to make referrals to the Coordinated Care Team for Truancy when families cannot be reached about attendance.

Ultimately, boosting attendance requires disciplined collaboration across the district, Velasco said.

“It’s a community effort,” she said. “It doesn’t take one person.”

Building Motivation

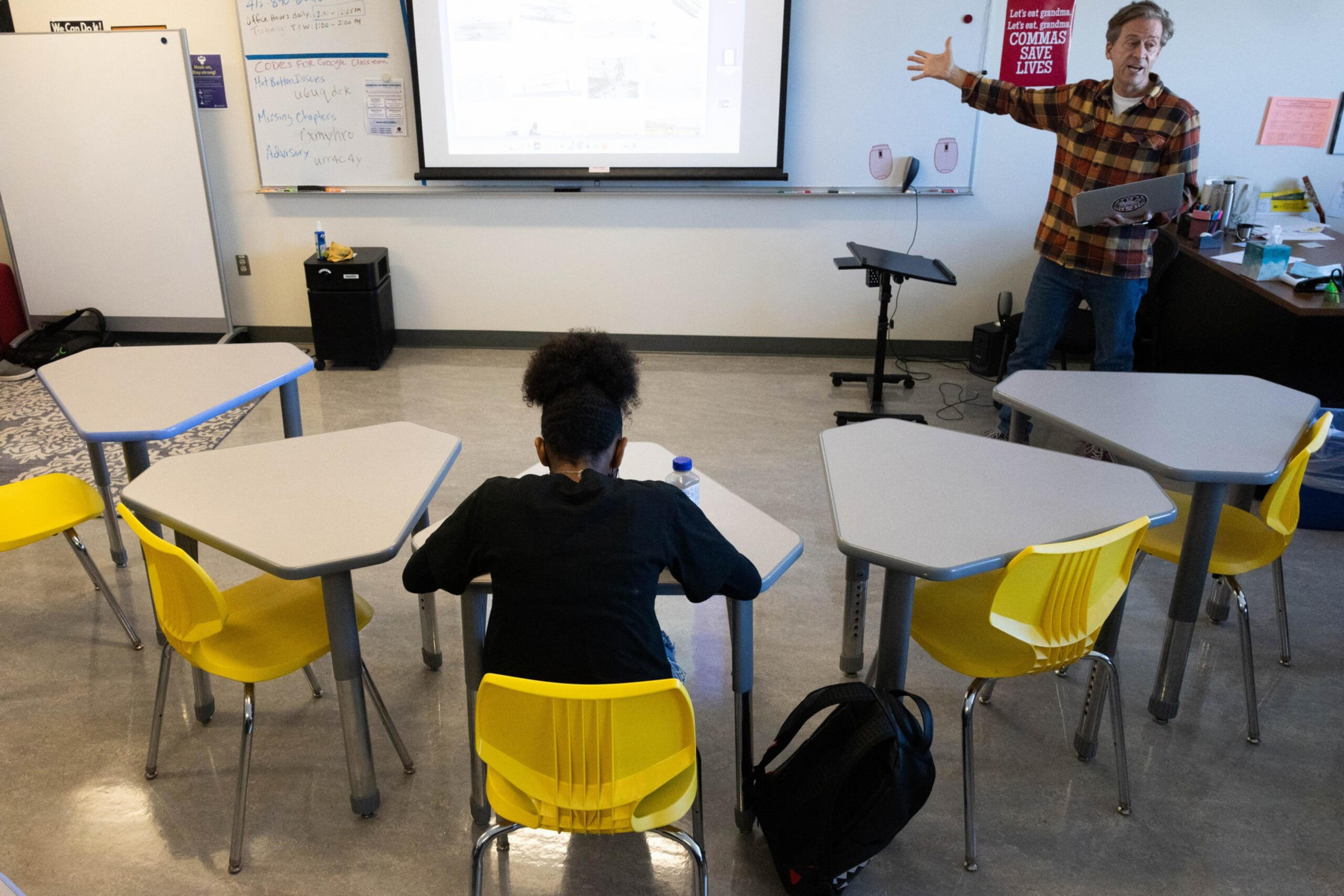

By the time many of her students end up at Independence High School, Principal Anna Klafter said they’ve already missed months of school. To respond to the heightened need for support, Independence hired an extra social worker to engage chronically absent students.

One recent meeting with a parent of an online student who wasn’t going to school at all revealed that her mom needed aid in trying to track down housing. SFUSD logged 2,342 homeless students in 2021 (opens in new tab), with potentially higher numbers expected (opens in new tab) to show in new data this fall.

“There’s all these little stories like that that you’re not going to get just by looking at the numbers,” Klafter said. “We have definitely seen the amount of our most at-risk students graduating rise sharply with the arrival of our [intensive] Tier 3 (opens in new tab) social worker.”

For Orellana Castillo, the Independence High School student who took construction gigs in lieu of going to class, it took a proverbial village to get him back on track.

Through slowly listening and building trust with Orellano Castillo, staff were able to cater school assignments and class credits to his passions under the independent study model. He was there nearly every day and graduated early in June at 16 years old. Now, the Mission District native studies at City College of San Francisco and wants to be a contractor in the future.

“I felt like they were actually trying to help me,” Orellana Castillo said. “That’s when I started doing my work. […] I actually got more motivated to come to school. I wasn’t even planning on going to college.”

Han Li contributed to this report.