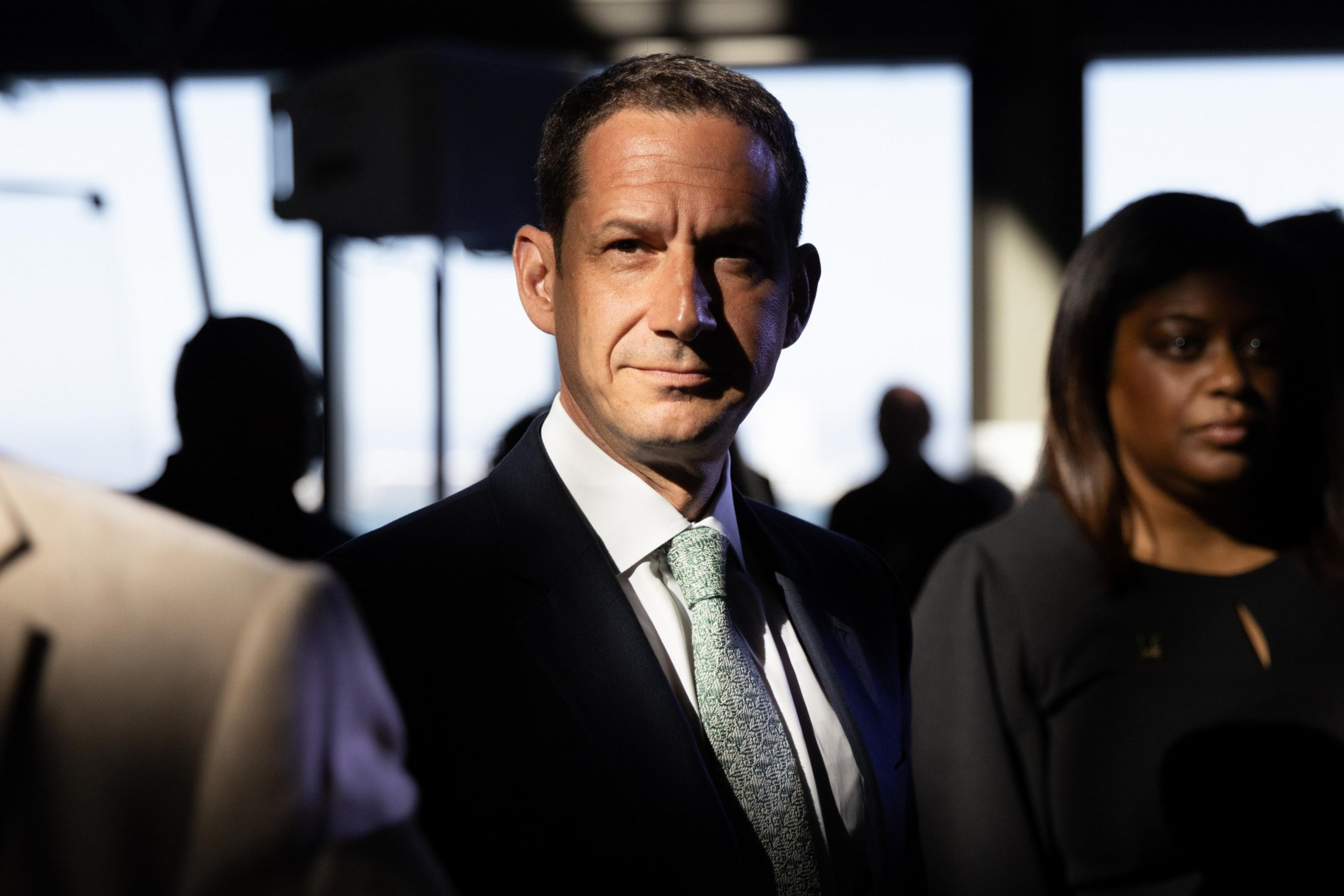

After nearly five months of executive-directive promulgating, collaborative legislating, elaborate policymaking, and all-around good-vibe generating (opens in new tab), Daniel Lurie arrives Friday at the most important day of his young mayoralty: the budget reaping.

For his first budget for the city and county of San Francisco — the current one is just shy of $16 billion — Lurie may be forced to spend his considerable political capital by pissing off a number of important constituencies. Either that, or he’ll thread the needle of pleasing as many people as possible. A tough job, sure. It’s the one he asked for.

That the budget will be balanced is not a subject of suspense — the city charter requires it. It’s how it gets balanced that matters. Past mayors have used all manner of accounting gimmicks to make the massive municipal ledger pencil out: liberal borrowing from reserve accounts, rosy assumptions about revenues yet to come, pushing out spending to future years, and so on.

Lurie has promised repeatedly he’ll avoid these cosmetic fixes that delay, rather than eliminate, a day of reckoning. Yet despite a passel of reports this week about services he is not chopping — cops, firefighters, DAs, public defenders — Lurie’s team has been mum about where he’ll slash.

As of early Wednesday, even well-connected city department pooh-bahs and elected officials told me they were still in the dark about the mayor’s budget determinations. Several hours later, The Standard reported there will be layoffs, perhaps around 150 in total. But the mayor will look to slim down city rolls not by cutting large numbers of people but by eliminating vacant positions. The whacking of nonexistent people could be in the neighborhood of 1,000 jobs, my colleagues reported.

Lurie is about to enter the lion’s den. The mayor’s budget is due June 1, kicking off a multiweek haggling process with the Board of Supervisors over passing it into law. Because the deadline falls on a Sunday, the mayor’s office says it will reveal the budget on Friday.

Lurie has only a few levers at his disposal to plug the two-year budget deficit, estimated by the controller’s office at $782 million. One is to lay off city employees, a tool that hasn’t been used in over a decade. (The last two waves came in 2010, after the repercussions of the financial crisis, and in the early 2000s, post-dot-com bust and 9/11.)

If Lurie does eliminate 1,000 positions, he’ll still be a long way from closing the yawning budget deficit. Given that unfilled positions typically represent anywhere from 5% to 10% of the city’s workforce of 33,000, slashing only 1,000 seats would be insufficient.

The problem is that cutting city employees, most of whom are covered by labor agreements and municipal employment codes, is not only politically dangerous but procedurally difficult. An elaborate process known as civil service “bumping” allows an employee whose job is eliminated to bump someone with less seniority from their position, even if that job is in a different part of the city. Such moves have a cascading effect, with one bumper bumping another, then another. And it takes a maddeningly long time to pull this off, with 60-day review periods the norm.

In other words, firing a city worker isn’t like laying off a corporate one.

But just because it’s hard doesn’t mean it shouldn’t happen. There is little question that San Francisco’s budget is out-of-control for a city of its size. A recent report (opens in new tab) from the political organization Grow SF illustrates the point well. Between 2012 and 2024, the city’s budget grew by $5.5 billion, and staffing grew by 27% — even though the population flatlined overall in the same period. San Francisco spends far more on staffing its core functions — $3,200 per resident — than any major city in California, typically by a factor of three. And that’s after factoring in San Francisco’s city-county status. All told, our city budget is larger than those of 17 U.S. states.

The other thing to watch in the mayor’s budget is how he handles two entities: the outsize nonprofit industrial complex and the for-profit contractor economy the city has built up over the years. A whopping one-third — $5 billion — of the general fund is not money the city spends on its own services and workforce but money it doles out to others. In effect, the city of San Francisco is a giant grantmaking organization, not unlike the anti-poverty outfit Tipping Point Community that Lurie founded — but far bigger. (According to a report by the think tank SPUR (opens in new tab), 10% of the city’s budget is grantmaking; 23% is for outside contracts.)

Entire departments — Children, Youth, and Their Families; the Mayor’s Office on Housing and Community and Development; the Human Rights Commission — effectively exist to hand out money to third-party organizations, rather than functioning as city agencies as citizens might assume.

How Lurie handles the challenge of dispensing this cash — which nonprofits get dinged, which get destroyed, which grants get extended, which departments get wrist-slapped — will determine not just the fiscal responsibility of his budget but also his success as mayor.

It’s a veritable “Sophie’s Choice” for Lurie. There’s no way he pleases everyone. But least pleasing of all will be if he punts on the tough calls the times require.