Tenderloin Housing Clinic, one of the city’s most prominent city-funded nonprofit housing providers, is heading toward a historic moment: its workforce could be the first in San Francisco that primarily serves the formerly homeless to go on strike.

The city funnels $1.2 billion annually to 643 nonprofits, 70% of which is spent on homeless outreach, permanent supportive housing, healthcare, and other key services for the city’s indigent population, according to the San Francisco Controller’s Office (opens in new tab).

Considered a vital tool in the city’s struggle against homelessness, the sector employs workers who are nonetheless “among the lowest paid workforce in San Francisco,” according to a June 8 Controller’s report. Average hourly wages range between $20 and $25 an hour, the report said.

At THC, roughly 300 people work in roles including front-desk clerks and janitors at its 24 single-room occupancy hotels (opens in new tab) and apartment complexes, and as caseworkers who manage the sometimes-intensive services at city-funded supportive housing. Organized with the Service Employees International Union Local 1021, their last contract expired in June 2020.

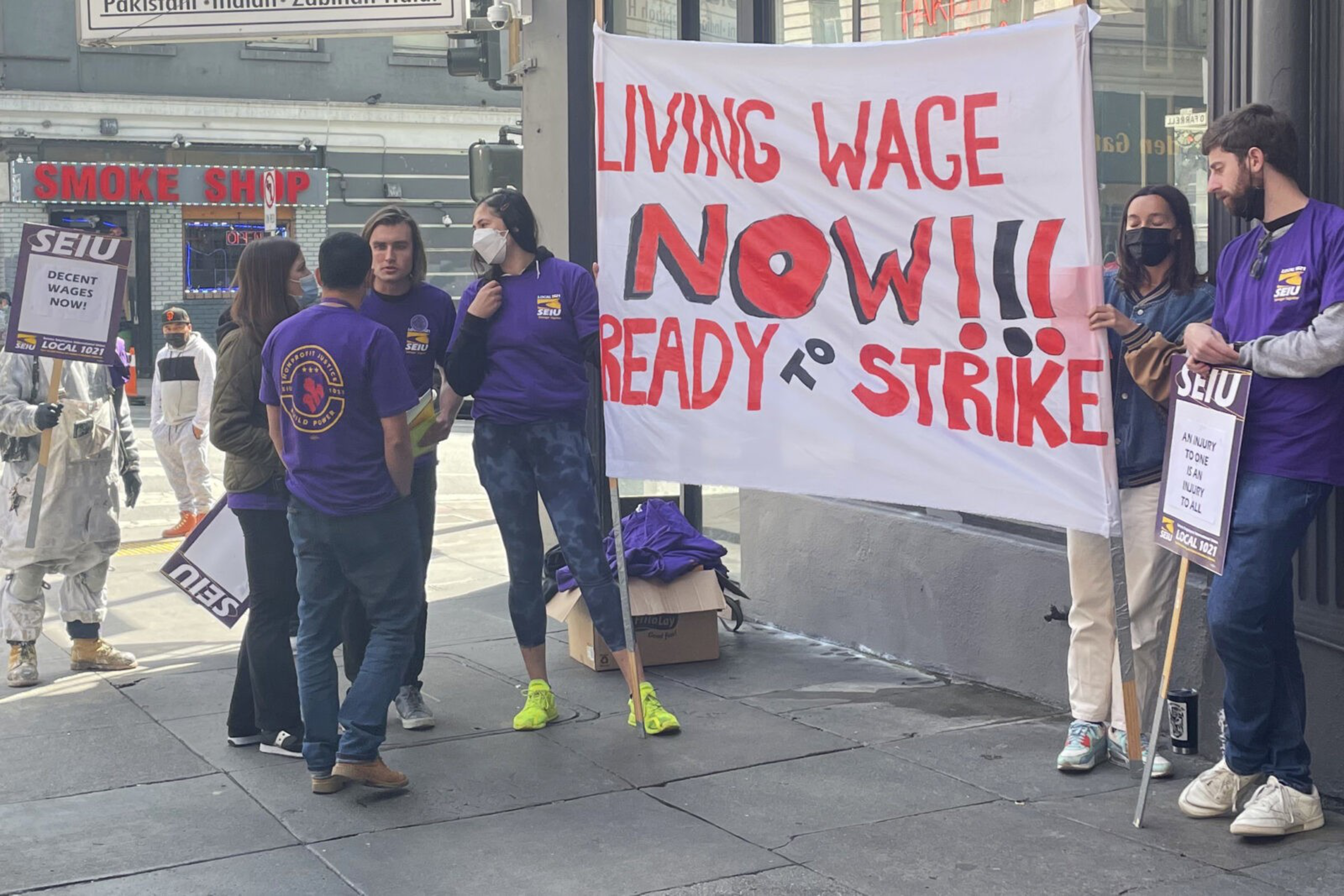

Earlier this spring, with negotiations still deadlocked, more than 99% of the bargaining unit voted to authorize a strike if the stalemate isn’t broken, organizers told The Standard. As of Wednesday, workers are still without a contract with no new bargaining sessions scheduled, organizer Evan Oravec said.

Generally considered the last resort in labor negotiations, a strike is the most radical tool in a union’s arsenal. Many city worker unions, including Muni drivers, are prohibited by law from going on strike.

A strike at a permanent-supportive housing provider would be uncharted territory, and lead to a serious disruption in services, with appointments canceled, maintenance requests unfulfilled and nobody at front desks monitoring who enters buildings.

Randy Shaw, THC’s longtime executive director, declined to comment at length when reached briefly on his cellphone June 27. At the time, Shaw said only that the dispute could be resolved as soon as “tonight or tomorrow.” He did not respond to subsequent requests for comment.

But as of Wednesday, more than a week after Shaw’s predicted resolution, management and workers were still far apart on key points including guaranteed wage floors and raises, Oravec said.

Though Mayor London Breed’s budget allotted (opens in new tab) $67 million over the next two years to raise pay for nonprofit workers—including a new $28-an-hour floor for skilled caseworkers, some of whom hold master’s degrees—that’s still below the $30 an hour “living wage” for a single person with no children in the city, according to MIT’s Living Wage calculator (opens in new tab). And front-desk clerks and other workers, many of whom are people of color, according to the city controller, earn even less than that.

Some, like Hattie Patterson, a front-desk clerk at THC’s Vincent Hotel who makes $19 an hour, live in subsidized housing themselves.

“If I wasn’t, I wouldn’t be able to live off the money they paid us,” she said in a recent interview. “I can barely make it now.”

Although THC’s union is the first representing nonprofit permanent supportive-housing workers to edge close to the red line of a strike, their pay structure is common throughout the city’s nonprofit sector, as a parade of workers, managers, and advocates told the Board of Supervisors during a June 8 hearing.

The poor pay leads to an unsustainable cycle of high burnout, constant turnover—and, finally, inefficient or underperforming services, a situation the controller acknowledged (opens in new tab).

In an email, Jeff Cretan, a Breed spokesman, declined to comment “on any discussions between providers and their workers,” but admitted there’s a problem.

“Attracting and retaining staff has been a challenge for the nonprofit organizations in this community—as well as many others and that is exactly why the mayor included $67.4 million in her budget to address these concerns,” he wrote.

Other experts agreed that the existing wages are inadequate.

“There are persistent frontline staffing issues at all the PSH in SF,” said Jamie Chang, an assistant professor of public health at Santa Clara University who studies homelessness and has done research in the Tenderloin.

Critics have at times questioned the wisdom of outsourcing vital services to what’s sometimes derisively called “the nonprofit industrial complex” rather than the city providing the services directly—at times suggesting that the current system encourages waste or graft. But experts note this arrangement saves money: Using city staffers to do the same work would require funding a city pension, thereby driving up the cost even more.

The pandemic appears to have triggered a new militancy in a once-docile nonprofit workforce. For a brief period, workers qualified for a $5-per-hour federally subsidized hazard bonus for essential workers. When it expired after a year, it was radicalizing, and may have been the final straw to convince workers a strike is necessary, noted John Logan, a professor of labor and employment studies at San Francisco State University.

Labor strife like that at THC is “years in the making,” but “taking [the bonus] away causes huge resentment,” he said. “That adds to the sense of injustice, that they’re treated unfairly.”

After the July 4 holiday weekend, following several months of regular negotiation meetings, it was not immediately clear what would precipitate a strike, though Oravec vowed workers would “move forward if we don’t see the kind of investment that will lift everyone up.”

In the meantime, strike or no strike, THC’s wage structure keeps key positions unfilled, workers said.

“No one wants to be a janitor at THC,” Patterson said. “The work is too dirty, and the pay is too low.”