San Francisco doled out more than $25 million in taxpayer dollars last year to dozens of charities that were blocked by state law from receiving or spending funds, an investigation by The Standard has found.

In what appears to be a citywide lack of due diligence, 18 departments—including Children, Youth and Their Families; Public Health (DPH); and the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development—failed to notice that they were paying out millions of taxpayer dollars to organizations whose nonprofit status had been revoked, suspended or tagged as delinquent by the state Attorney General’s Office prior to the payouts.

This negligence occurred as San Francisco gave more than $1 billion to 600-plus nonprofits last year, relying on them to help solve some of the city’s most intractable issues. Polling by The Standard has found widespread discontent with city government and its seeming lack of progress in addressing homelessness, drug overdoses and poor-performing schools.

Meanwhile, the city has become an international punching bag over quality-of-life issues, gaining a reputation for throwing money at problems without showing results.

As of early December, the city had active contracts with nearly 140 nonprofits that failed to comply with state registration requirements, potentially leaving San Francisco on the hook for over $300 million with scofflaw charities.

Experts on nonprofits and government ethics who were contacted for this story expressed alarm at the scale of the city’s apparent lack of oversight, and they questioned local officials’ rigor in vetting these contracts.

The contracts identified in The Standard’s review deal with confronting some of the city’s biggest crises: homelessness, drug addiction, assisting disadvantaged schoolchildren and offering subsidized health care to low-income residents and communities of color.

“My first reaction is that the public interest is not being served in San Francisco with the amount of money going to nonprofit organizations that don’t have current licenses,” said John Pelissero, a senior scholar in government ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University.

The Standard launched its review after the United Council of Human Services, an organization responsible for providing homes and shelters for homeless people in the Bayview, was referred to the FBI and District Attorney’s Office for criminal investigation.

In November, the City Controller’s Office released an audit that found the organization had mismanaged funds and operations after receiving tens of millions of dollars in city and federal grants. Along with the City Attorney’s Office, which reviewed the findings, the agency recommended a criminal investigation. City officials were surprised to later learn that the Attorney General’s Office had suspended the United Council of Human Services’ nonprofit status over the summer.

The Standard’s new findings were confirmed by the City Controller’s Office, which noted that it is now working with the City Administrator’s and the City Attorney’s offices to issue guidance to departments to make sure the nonprofits either come into compliance with state law, or risk losing their city funding.

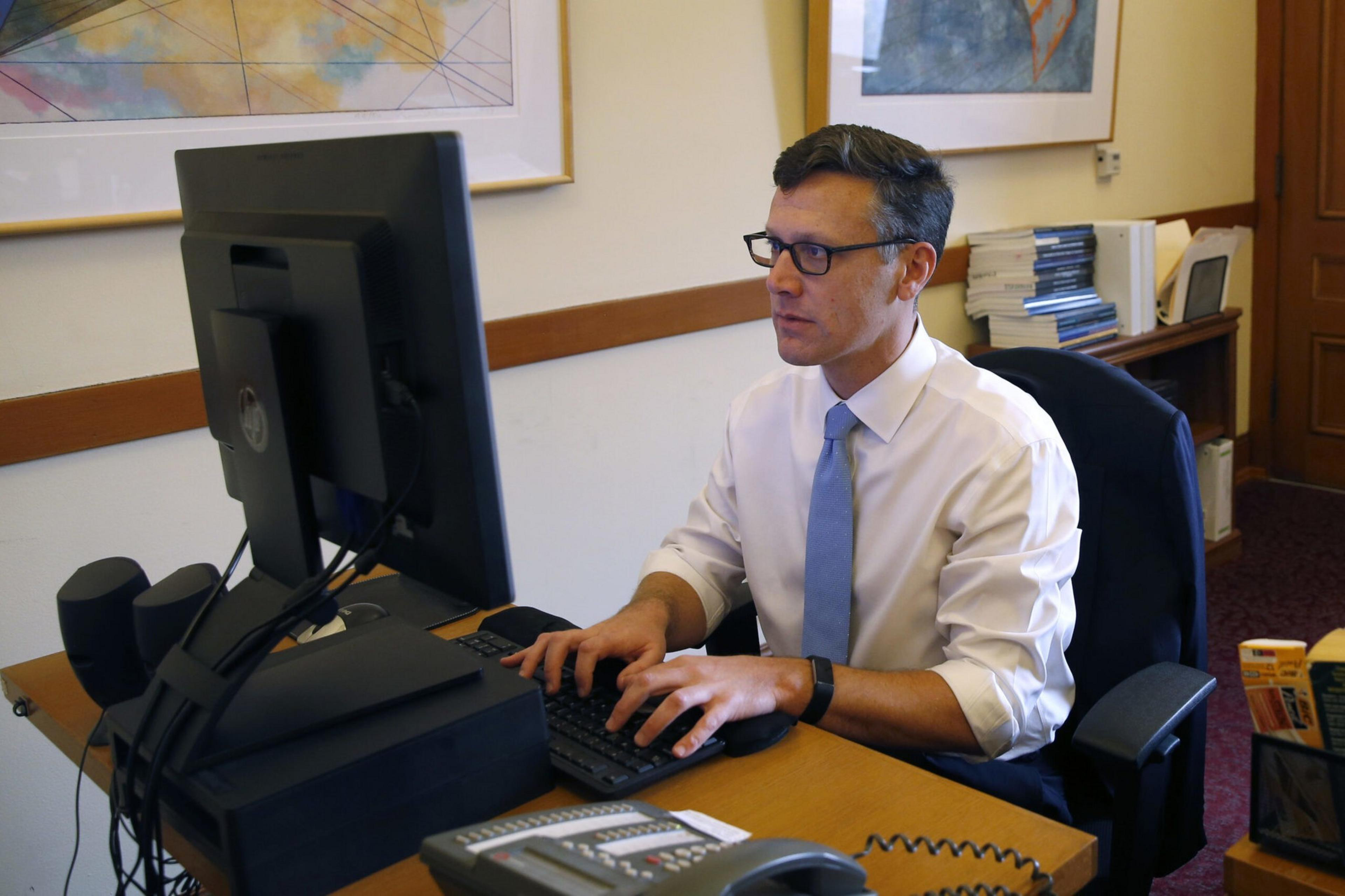

“Our grants and contracts require recipients to comply with local, state, and federal law,” City Controller Ben Rosenfield said in a statement. “City departments should not do business with organizations that are not permitted by the state government to operate in California.”

Beyond the $25 million the city paid since last summer to nonprofits after they lost their good standing, another $65 million was issued to organizations that eventually lost their good standing. However, it’s unclear whether or not the payments to the latter group came before or after they fell out of compliance.

Jen Kwart, a spokesperson for City Attorney David Chiu, said the city’s lawyers will work with the controller to “ensure grant and contract recipients are in good standing.”

“The City Attorney’s Office is committed to rooting out waste and making sure public dollars are spent fairly and efficiently,” Kwart said.

The Standard contacted 10 city departments with detailed questions on the findings. Officials refused to address why, in violation of state law, public funds were given to so many nonprofits that were out of compliance, or whether a status check with the state Attorney General’s Office is part of their contract approval process.

“We look forward to receiving guidance from the Controller’s Office on working with our nonprofit community-based providers to ensure they are in good standing with all applicable requirements,” a spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office said in a statement.

Nonprofits in California are required to annually renew their registration. Those that fail to do so will lose their “good standing” and enter delinquent status, according to the state Attorney General’s Office. Organizations that fail to renew after one delinquent year are suspended. If another year passes without the issues being resolved, the organization’s nonprofit status is revoked.

Charities that are not in good standing are prohibited from soliciting money for charitable purposes, retaining staff, providing services and spending funds, the Attorney General’s Office said. Nonprofits that continue to operate while not in good standing can face fines and civil or criminal complaints.

Of the organizations found to not be in good standing as of December, two were suspended, five were revoked and 132 were delinquent. Since then, some of the nonprofits have resolved their filing issues and come back into good standing with the state.

The reasons why the organizations were found to no longer be in good standing range from relatively minor one-time filing errors to flagrant, yearslong disregard for paperwork.

“It’s emblematic of the city giving money without any oversight,” said a San Francisco attorney who asked not to be named because they work with nonprofits in the city. “This is basic oversight and the city can’t even do that, so they’re certainly not checking to see whether these nonprofits are actually producing results.”

The out-of-compliance organizations range from city-aligned nonprofits like the San Francisco Parks Alliance, which was involved in the City Hall corruption scandal and is currently listed as delinquent, to community health providers that annually receive tens of millions of dollars.

Delinquent organizations, in certain cases, can make their way back to good standing or probationary status by simply communicating why an error occurred or submitting payments and missing paperwork. Many of the nonprofits and city departments reached for comment for this story were unaware the nonprofits were not in good standing.

Swords to Plowshares, a nonprofit that provides supportive housing to local veterans and has more than $20 million in contracts with the city this fiscal year, fell into delinquency in August 2022. The nonprofit wasn’t aware it had lost its good standing with the state until a donor alerted them in October, said Colleen Murakami, the organization’s chief development officer.

Renewing the California registration fell through the cracks when its chief financial officer departed in May. After learning about the lapse, Murakami said, the organization submitted forms and is now back in good standing with the state.

Murakami acknowledged that Swords to Plowshares made a major clerical error in letting the state filings slip, but she emphasized that the nonprofit stayed up to date with its annual audit and IRS filings, which provide more details into the organization’s actual performance.

“The delinquent status does not, in any way, say anything about your ability to be a good steward of public dollars,” Murakami said. “It’s literally saying you didn’t file a form.”

Paul Dresher Ensemble, an arts organization that puts on music performances and provides artists residencies, received over $41,000 after its nonprofit status was revoked in February of last year. The organization has another grant worth the same amount pending, which could be at risk ahead of a March concert it will oversee at the Presidio Theatre.

Paul Dresher, a music composer and the eponymous founder of the organization, told The Standard that his organization clearly dropped the ball after filing forms, but it’s not clear why they stopped filing for renewal after 2009. He said he started filing forms and paying fees last year to come back into compliance with the AG’s Office.

“I think most of us are just struggling to do our work and are running afoul of some bureaucratic thing,” Dresher said. “Most of us small arts organizations are just trying to do our work.”

The Registry of Charitable Trusts did update its filing requirements in 2021 (opens in new tab), which may, in part, explain why so many nonprofits have missing paperwork.

San Francisco Students Back on Track, an interfaith nonprofit designed to help K-12 school children in the Western Addition, had its nonprofit status suspended in September of last year. The city has already paid the organization more than $83,000 this fiscal year and has future awards worth more than $250,000.

Jonathan Butler, the executive director of SF Students Back on Track, said in an email that the organization immediately submitted forms to the AG’s Office to correct the issue after becoming aware of the suspension in the fall. The organization’s registry status, however, is still listed as suspended on the state’s website (opens in new tab).

Two experts in nonprofit accounting told The Standard in interviews that a delinquent status is not necessarily a red flag, but any organization that receives taxpayer money should be under intense scrutiny—especially when they’re charged with confronting major crises that appear to be getting worse to the public.

The Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing has the largest total of remaining contracts with nonprofits that lost their good standing with the state, adding up to almost $88 million as of December.

The Attorney General’s Office recently filed a lawsuit (opens in new tab) against a Riverside County charity for a wide range of mismanagement violations, including soliciting donations while the nonprofit was not in good standing with the Registry of Charitable Trusts and the IRS.

State officials declined to comment on whether they would investigate any San Francisco charities that have received or spent funds in violation of state law.