Residents in San Francisco often bristle at the thought of a drug rehabilitation center opening near their homes, as such facilities carry the perception that they are accompanied by an influx of brazen drug sales and associated violence.

But the leaders of the Minna Project, a rehab center in the South of Market neighborhood that began accepting clients from city jails in May, hope to become stakeholders in the community instead. Scheduled for a ribbon-cutting ceremony next Thursday, June 9, it will initially host 12 clients—with a total capacity of 80—in a drug-free, transitional-housing environment with supportive services on site and an initial yearly budget of $4.7 million.

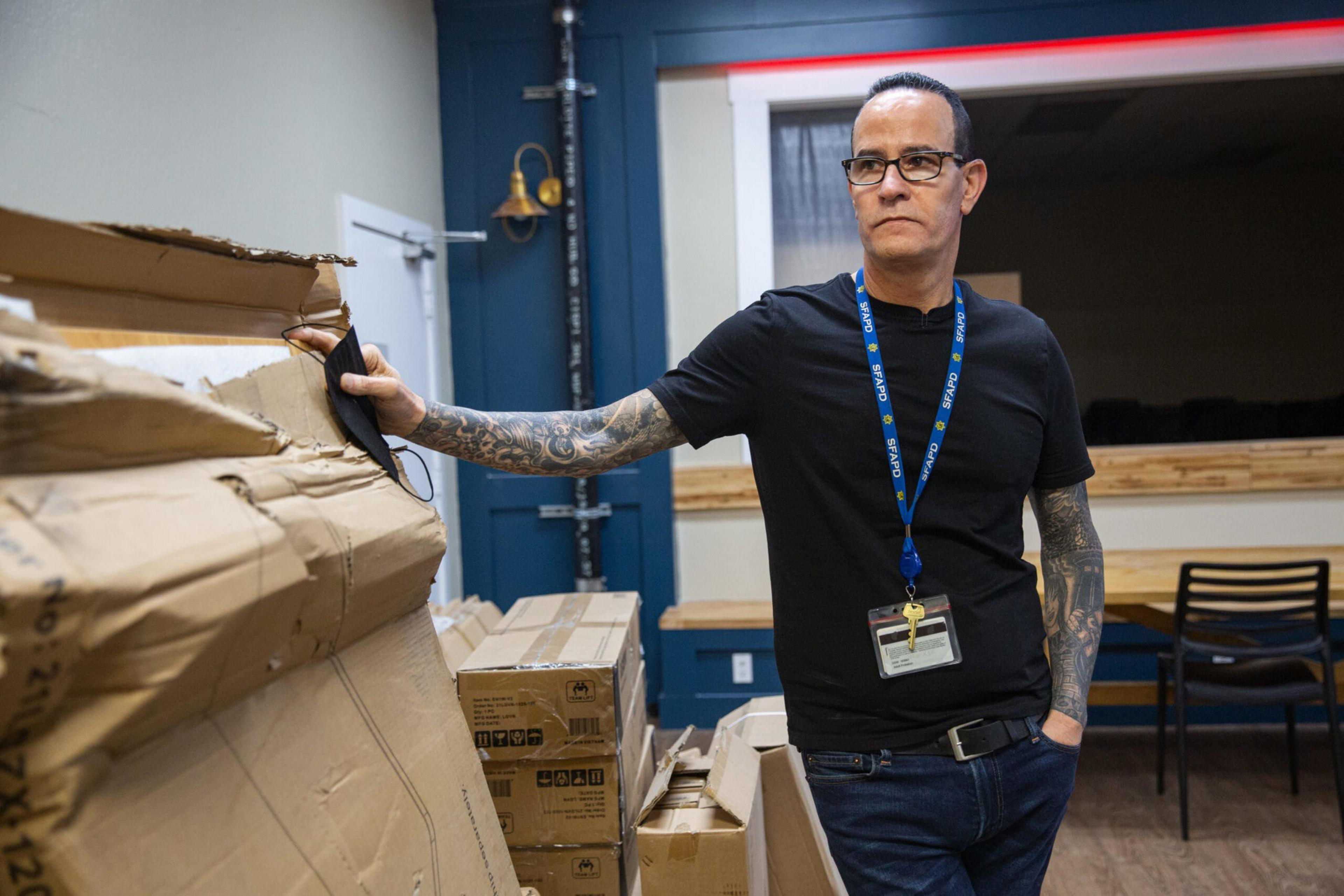

Steve Adami, the Director of Reentry Services, said he designed the Minna Project with the intention of revitalizing both the streets outside of the building as well as the lives of its guests.

“There are no tents out front, and there’s no drug dealers or syringes on the ground,” Adami said. “It’s an environment that’s safe, [and] that’s free of drugs, so people have the right to recover, reclaim their place in the community and live their lives.”

Undoubtedly, the facility—located at 509 Minna St., less than a block from where a 16-year-old girl was found dead from an overdose earlier this year—sits in a troubled neighborhood. SoMa has seen 17% of the city’s overdose deaths (opens in new tab) in 2022 and has experienced a marked increase in shootings.

In launching this program in that location, Adami has placed himself in the crosshairs of a debate on how to treat substance abuse. He is, in short, a firm proponent of abstinence, often using his Twitter platform (opens in new tab) to take aim at harm reduction, the philosophy that aims to destigmatize and mitigate the worst effects of drug use. Although he says that he is open to working together on solutions, it’s clear he believes harm reduction is not synonymous with true recovery.

As a practice, harm reduction started during the 1980s as an underground effort to combat the HIV/AIDS epidemic among intravenous drug users. Its success came in introducing measures like needle exchanges, under the widely cited mantra of “meeting people where they are.” As the locus of the drug overdose crisis has shifted to fentanyl abuse, San Francisco has embraced these efforts, pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into drug treatment programs that provide people with tools to safely continue using illicit substances, frequently under supervision and with ready access to other social services.

Measured by the number of lives saved, harm-reduction has clearly worked. Since Dec. 13, the city’s emergency response teams have reversed over 1,000 overdoses (opens in new tab) using the lifesaving, FDA-approved medication Naloxone. Additionally, nonprofit organizations working among at-risk populations report many more overdose reversals, with the San Francisco AIDS Foundation reporting nearly 500 reversals per month.

However, the approach has its skeptics who say that it’s ineffective in helping people get sober. Like many advocates within the recovery community, Adami contends that the city has veered too far into practices that don’t actually diminish harm, but encourage it. The city opened a facility in January with the intention of linking people to treatment using harm reduction principles, which that means it allows people to use drugs while in the facility, but thus far the program’s staff have recorded more overdose reversals than completed linkages.

“What you see out on the streets is not harm reduction,” said Cedric Akbar, executive director of the nonprofit Positive Directions Equals Change (opens in new tab), adding that the real goal is to “reduce the risk” of clients using drugs.

Akbar started a 2020 pilot program in the Bayview called the James Baldwin House, which the Minna Project is modeled after. The James Baldwin House reported that none of its participants returned to jail within the first 15 months of operations, according to Adami.

While the Minna Project is drug-free, it’s also unique in that clients aren’t kicked out entirely if they relapse. Instead, they may be provided with medication-assisted treatment, Adami said.

“It’s a drug-free environment where people cannot use drugs in this program, but it does embrace all the core tenets of harm reduction,” Adami said. “We not only reduce harm on the person’s life but the community and others in the program.”

For starters, the program requires that clients complete three hours of community service every Saturday in exchange for three meals a day and a private room to sleep in. When people relapse, the staff sends them to a separate detox program for up to a week until they are ready to return.

Adami has also personally met with neighbors in the area, hoping to assure them that his facility won’t lead to havoc.

Greg Brueggemann, who lives next door to the Minna Project, told The Standard that he was concerned about its opening—until he spoke with Adami.

“I actually wrote a letter to the supervisors expressing my concern,” Brueggemann said.

He said that once the city started housing people at the Americania and Good Hotels on Seventh Street during the Covid pandemic, the situation in his neighborhood became more dire. But after touring the Minna Project and other programs run by Adami, his mind was at ease.

“Up until the pandemic, we had really been improving … but there’s open-air drug dealing, open-air drug-taking all around their hotel buildings,” Brueggemann said. “Steve seems like a straight-shooter. I see [his staff] out cleaning and power washing the sidewalks. … I’m happy to be their neighbor.”

But challenges await the program as its clients will be reminded on a daily basis what they’re recovering from.

“Allowing people to use drugs and alcohol on the streets is disregarding to the people who are in recovery,” Akbar said. “All we ever wanted was a place where people can come to a safe environment and not use any drugs or alcohol. … As we looked around the city, that wasn’t happening anymore.”