California Gov. Gavin Newsom, declaring himself “disgusted (opens in new tab)” with the state of San Francisco’s streets, last week jumped into a fraught debate over how to combat the drug addiction crisis with a new program that would allow judges to sentence those with substance abuse and mental health issues to treatment.

Newsom’s CARE Court program, which he plugged once again in his State of the State Address (opens in new tab) Tuesday night and still requires approval by the legislature, is the latest push from politicians intent on helping those deemed unable or unwilling to help themselves. It comes a little over two months after current Mayor London Breed garnered national attention by declaring a state of emergency in the city’s Tenderloin district and vowing to end the city’s de-facto tolerance of public drug sales and consumption—or, as she put it, “all the bullshit that has destroyed our city.”

Breed’s suggestion that extra police officers would be deployed to the Tenderloin (opens in new tab) to arrest more drug dealers in the area—already the city’s epicenter for drug arrests—struck a nerve. So did her declaration that anyone caught using drugs out in the open would be presented with two options: get help or go to jail.

“We are not giving people the choice anymore,” she said. “We are not going to walk by and let someone use in broad daylight.”

Breed’s speech was interpreted as an endorsement of what centrist Democrats, moderate Republicans and desperate family members of people with intractable substance-abuse problems across the country are demanding—a legally binding means of forcing people to address their addiction problems.

Embraced by President Joe Biden during the 2020 election cycle, “mandatory treatment” is framed as a kinder and gentler alternative to imprisonment and a responsible way to address the ugly status quo in neighborhoods like the Tenderloin or Skid Row in Los Angeles. Many drug addiction specialists disagree, pointing to research that concludes forced treatment doesn’t work, and even going so far as to call it incarceration in disguise.

In San Francisco, efforts to force people into rehab are further complicated by logistical issues—it’s not clear whether there are enough treatment beds, even for those who want them—as well as medical questions. While some treatment programs offer patients drugs like methadone or Suboxone to help manage withdrawal symptoms, others expect people to go cold turkey.

Add it all up, and a policy conundrum emerges: Mandatory treatment is an increasingly popular talking point and a seemingly common-sense approach to the twin crises of opioid overdoses and ballooning stimulant abuse (opens in new tab). Yet many experts in the field reject the approach, and it is far from clear if and how it might ultimately make a difference, either for individual drug users or for conditions on the city’s streets.

Tough Love

Currently, in the United States, substance use disorder is grounds for involuntary commitment in more than 30 states. Allowing a nonviolent offender to choose treatment over jail is already a key component of diversion programs in San Francisco.

Proponents say mandatory treatment would help make San Francisco a place where it’s easy to get well, instead of merely get high. When juxtaposed against the city’s grim death toll from drug overdoses—1,350 people dead over the past two years, almost double the deaths attributed to Covid, according to the San Francisco Department of Public Health (opens in new tab)—using the police and the courts to herd recalcitrant drug users into treatment looks to many like the humane choice.

Mandatory treatment is having a moment locally, in part due to some very vocal advocates. Chief among them is Michael Shellenberger, the Berkeley-based author of the anti-progressive polemic San Fransicko, who argues that hands-off “harm reduction” programs—which emphasizes keeping users healthy through efforts such as needle exchanges and supervised consumption sites, rather than threatening them with punishment—is what created the Tenderloin’s sidewalk morality play. Mandatory treatment is a key mechanism for ending the mayhem, he argues.

And San Francisco isn’t the only place where the idea is gaining ground. Recent polling reveals (opens in new tab) compulsory treatment is extremely popular in Canada, even as the country has embraced a full range of harm reduction programs that in some cities extends even to guaranteeing a clean supply of heroin and other drugs (opens in new tab).

Powerful anecdotes help make the case for forced treatment. Tom Wolf, a recovering opioid addict who spent time homeless in the Tenderloin, credits the police officer who arrested him in 2018—triggering a journey from county jail, where he was forced to stay clean, to rehab and onto sobriety, where he is today—with saving his life.

Wolf’s experience has turned him into a minor local celebrity. He is frequently quoted in the media, and he appears as a main character in San Fransicko. Wolf is also featured in a new documentary alongside celebrity doctor Drew “Dr. Drew” Pinsky (opens in new tab), a mandatory-treatment advocate who was briefly floated as a candidate for Los Angeles County’s homeless commission.

Wolf himself is presented as a folksy data point supporting involuntary treatment—even though he admits that voluntary treatment is preferable.

“I can line up at least 10 people right now that got clean in handcuffs. But voluntary treatment is always better,” he said in an interview with The Standard.

Wolf went into involuntary treatment via a city drug court. Of the 90 people who started his abstinence-based Salvation Army rehab program, 22 completed it, he said, although one of the 22 recently relapsed and is currently in treatment at Walden House.

Then again, he continued, “Here I am, four years later, clean and sober. How’s that for evidence, buddy?”

Addiction medicine specialists generally agree that entering treatment voluntarily is far more likely to succeed than any form of coercion, but some support for “tough love” approaches can also be found in academic circles. Keith Humphreys, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University who studies addiction and has helped lay the intellectual foundation for drug-policy reforms including marijuana legalization, is among those who say it can work.

He points to a 2015 article in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (opens in new tab) which found that among 160 people enrolled in treatment between 2007 and 2010, “those who were mandated” were more likely to finish their programs.

“People are surprised by this only if they assume the typical person in addiction treatment came in with no pressure on them whatsoever, but that is rare,” he said in an email. “Usually the boss, the spouse, the kids leaned on them to go, or the grim reaper did when their doctor said, ‘I’ve looked at your liver tests, and if you keep this up, you won’t last another year.’”

“A court-mandate is formalized pressure,” he added. “But most people are under pressure of some form.”

Politics & Practicality

Statistically speaking, most efforts at treatment for substance-abuse fail. Half of people who enter treatment don’t last a month (opens in new tab) before they’re out of rehab and off the wagon. Some are kicked out for breaking curfew or relapsing. Others are simply disinterested in whatever was on offer.

Some programs are “abstinence-based,” meaning a client fails and is kicked out if they relapse at any time during their stay, be it three weeks or ninety days.

Other programs offer what drug researchers call “evidence-based” treatment—that is, approaches current medical science says are most likely to work. For opioid users, evidence-based treatment would offer them opioid agonists like Suboxone, a drug (opens in new tab) that combines a long-release opioid, buprenorphine, with the overdose-reversing drug naloxone, better known by its brand name, Narcan.

For methamphetamine users, evidence-based treatment is in shorter supply, as there is no Suboxone equivalent for those dependent on speed. However, “contingency management (opens in new tab),” recently legalized in California, in which meth users are literally paid to stay clean, has shown some promise.

In the U.S., most treatment options are not evidence-based. Research recently published (opens in new tab) in the Journal of the American Medical Association found (opens in new tab) only 29% of programs surveyed nationally offered long-term opiate-agonist therapy, with many more either not offering or “actively discourag[ing]” the treatment. Non-medical treatment is also the “most common detox pathway,” in San Francisco, according to the city’s Department of Public Health, though the agency declined to provide any figures.

Critics of mandatory treatment say the lack of evidence-based programs is yet another reason to avoid the practice.

“The literature does not support mandatory treatment on any level to help the public health situation,” said Daniel Ciccarone (opens in new tab), a physician and professor of family community medicine at the University of California San Francisco, who studies drug addiction.

Ciccarone doubts Newsom’s CARE program will work—even if it survives legal challenges and is accepted by the courts. “I think it is backwards and likely to fail,” said Ciccarone. “The solution to homelessness is housing; make it ‘supportive housing’ and couple it with substance treatment, case management and mental health services; anything short of that will be a revolving door.”

A 2015 meta-analysis of nine studies examining involuntary treatment around the world found that “evidence does not, on the whole, suggest improved outcomes related to compulsory treatment approaches, with some studies suggesting potential harms.” While the issue is under-studied in the United States, research from Russia and (opens in new tab)Mexico (opens in new tab)published over the last decade agrees compulsory treatment is ineffective in solving drug addiction—and amounts to imprisonment in disguise.

“Global evidence indicates that mandated treatment of drug dependence conflicts with drug users’ human rights and is not effective in treating addiction,” Karsten Lunze, a professor at the Boston University School of Medicine found (opens in new tab).

Given the doubts over the efficacy of involuntary treatment, why is it so alluring for some advocates?

“On an individual level, you can always find someone who says they benefited from being shown ‘hard love,’ or ‘tough love,’ whether it was their family or a police officer or a court,” said Ciccarone. “It may actually work—politically,” he added. “From a public health point of view, will it reduce overdoses? Probably not.”

No Moves Yet

Several months into Breed’s Tenderloin emergency declaration, neither forced treatment nor the city’s safe injection site have materialized.

Asked directly via email if Breed supports involuntary commitment for people with drug addiction—or if the police would begin funneling drug users into rehab, or when—Jeff Cretan, the mayor’s chief spokesperson, did not respond.

In an earlier email, Cretan pointed out that Breed has since 2019 supported a proposal from state Sen. Scott Wiener, a former city supervisor, to expand the state’s involuntary commitment laws to include “those who are truly suffering and unable to care for themselves,” including someone with a dual diagnosis of mental health and substance abuse issues.

“The mayor has also said repeatedly that as we make more investments in housing, shelter and treatment, we need people to take those options when they are made available, and not be allowed to stay on the street,” Cretan added.

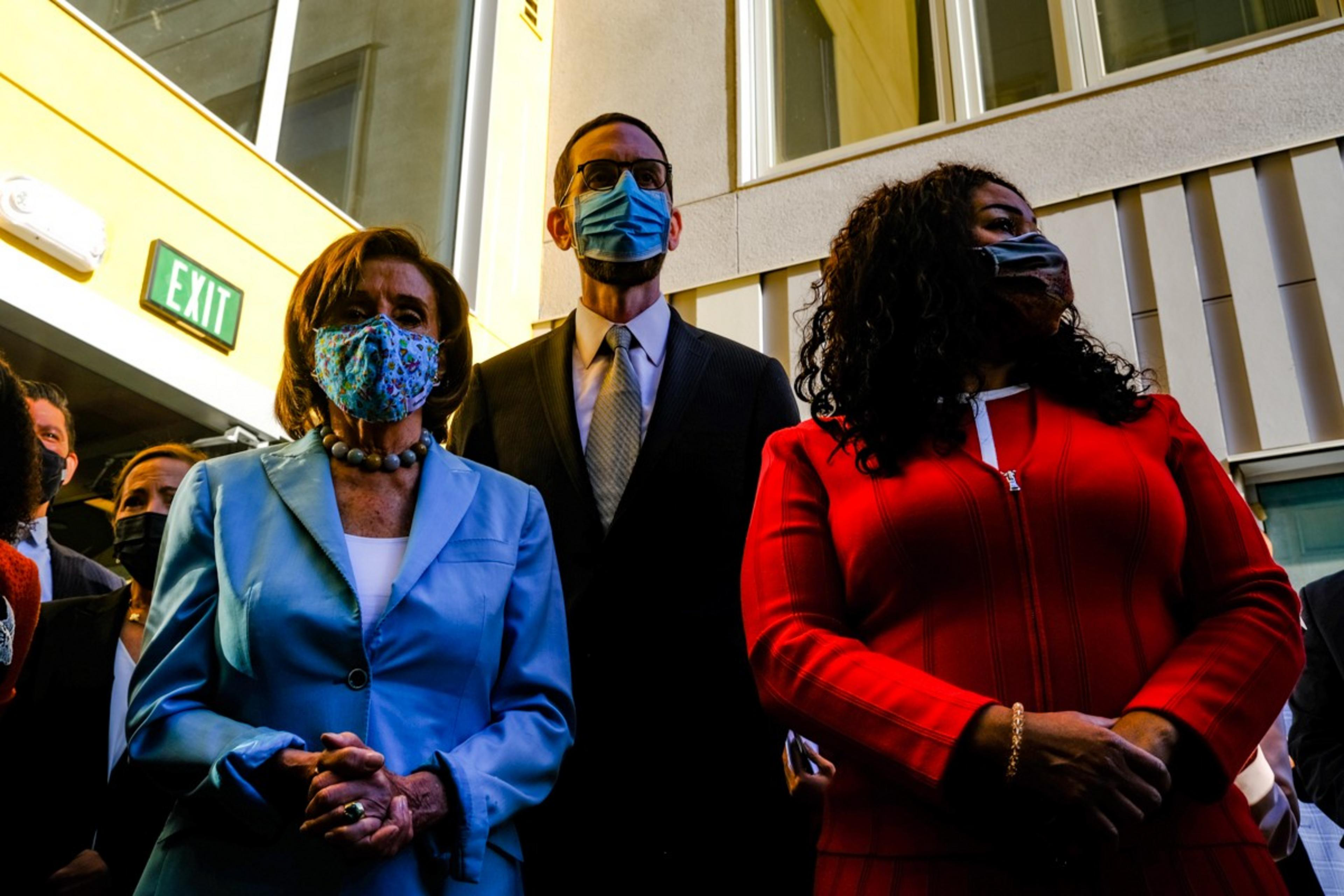

Spokespeople for District Attorney Chesa Boudin refused to discuss whether the city’s top prosecutor supports mandatory treatment, though Boudin did appear at a December press conference held by HealthRight360, one of the city’s leading treatment providers, in which involuntary treatment was cast as a regressive return to a punishment-first drug war paradigm.

Leo Beletsky, a professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University who has extensively studied mandatory rehab, said the idea was ultimately something of a fig leaf—though maybe one that satisfies the current political zeitgeist.

Said Beletsky: “It’s much easier to say, ‘OK, well, we’re not going to incarcerate people, we’re just going to incarcerate them and call it treatment.’”

Insufficient Capacity for Care

Advocates say what would work best in San Francisco, beyond solving underlying social problems like the housing crisis, is expanding the city’s treatment capacity and making sure that the programs adhere to best practices.

Data on the availability of treatment beds in San Francisco is sketchy, as are exact figures for how many programs are on offer in the city, but the available numbers are not encouraging. According to a recent statement provided by the DPH, the city has 2,200 “spaces” in its “residential care and treatment offerings,” with “over 400 spaces being added.”

However, according to a recent publicly available snapshot on findtreatment-sf.org (opens in new tab), the city advertised a capacity of 500 substance-use disorder treatment beds in three categories and had only a few dozen available. Of the 58 “detox now” beds, 48 offered medical detox. “There remains reduced capacity at some sites due to Covid and the required safety precautions,” DPH spokesperson Zoe Harris wrote in an email.

These figures only include treatment beds contracted by DPH and not beds offered by nonprofit service providers who might contract with the courts.

A 2016 DPH estimate (opens in new tab) put the number of intravenous drug users in San Francisco at roughly 22,000. That figure has been repeated as gospel ever since. The number of hard drug users who may snort or smoke their stuff is surely higher, especially considering that fentanyl and its analogs—often smoked rather than injected—didn’t really take off in the Tenderloin until around 2018, and drug experts like Daniel Ciccarone of UCSF identify stimulants as the current overdose crisis’ “fourth wave.”nonprofit service providers who might contract with the courts.

Critics also question the city’s commitment to “social” or “non-medical” treatment programs–the most common approach, according to DPH–which don’t offer those struggling with an opioid addiction the option of an agonist like Suboxone.

Whatever the specifics of the treatment, unless the city built a new dedicated treatment facility or converted the San Bruno jail to a drug-rehab center—a proposition some experts think is smart policy (opens in new tab)—committing even a fraction of local addicts to treatment is not currently something the city can physically do.