Cathy Robb was traveling around the country in an RV when she found out that her son Bryan, who had moved to San Francisco a year and a half earlier after the death of his wife, was in the hospital with a bacterial skin condition called cellulitis on his legs. He was in the throes of a fentanyl addiction, which causes him to fall asleep while standing up, putting unusual stress on his legs and leading to infection.

When they heard the news, Robb and her husband redirected their RV to San Francisco.

Their 35-year-old son was walking with a cane and could barely fit his shoes over his swollen feet—but for the first time, he was showing a desire to get clean.

Bryan asked his parents to take him to a methadone clinic, often the first step for people seeking recovery from opioid addiction. Instead, he fell into an all-too-common pattern for drug users seeking treatment in San Francisco: He couldn’t get admitted right away, and soon after returned to using.

“There was a really small window, and the window slammed shut because they didn’t have anyone to help him,” Robb said.

Despite $71 million spent on substance abuse treatment programs in fiscal year 2021, people involved with the city’s network of drug treatment and behavioral health facilities describe staffing shortages that can make it very difficult for people to access treatment when they’re most motivated to seek change. For some, it can be just a matter of hours before they go back to using.

Cedric Akbar, director of forensics at the Westside Community Services methadone clinic in the Fillmore district, said that his program turns away between five and 15 people per day due to staffing issues. Akbar described patients coming into the facility shaking from their withdrawals and leaving without relief.

“It’s the most miserable condition a person could possibly be in. They’re thinking that they’re close to death,” Akbar said. “We have to try and refer them somewhere else.”

Labor shortages are affecting many different workplaces at the moment, but the issue is especially pronounced at the city’s behavioral health facilities. Nonprofits and other publicly-funded facilities at the front lines of the city’s drug crisis struggle to compete with wages offered by private clinics, leading to high turnover rates and an inexperienced workforce. The pool of experienced workers who are willing to take pay cuts and lose benefits to work in the public sector is limited. And in the case of methadone clinics, patients taking the first step in recovery often need long-term, intensive treatment.

“When they can’t get in, then they go outside and they get some dope,” said Cregg Johnson, a former counselor at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital’s opiate treatment program. “We just had to do the best we could with the staffing shortages…We would just have to shut down the intake office.”

The need for more behavioral health workers is longstanding and isn’t unique to San Francisco. The U.S. is about 1.9 million behavioral health workers short of addressing the country’s drug addiction crisis, according to a survey by the federal Substance Abuse and National Mental Health Services Administration (opens in new tab). In San Francisco, a May report by the Budget and Legislative Analyst found a shortage of case managers at behavioral health clinics, leading to long wait times for certain services.

At methadone clinics, the full intake process—which involves a drug test, a physical exam and questionnaires about a person’s medical history—takes two to three hours to complete and is just the first step in what can be a hard-to-navigate journey.

Methadone, a synthetic narcotic that is stronger than other withdrawal medications and used to stave off cravings, is heavily regulated: Methadone patients are required initially to show up in person and undergo counseling to receive daily dosages. That alone can present challenges for patients who are homeless or in other unstable circumstances.

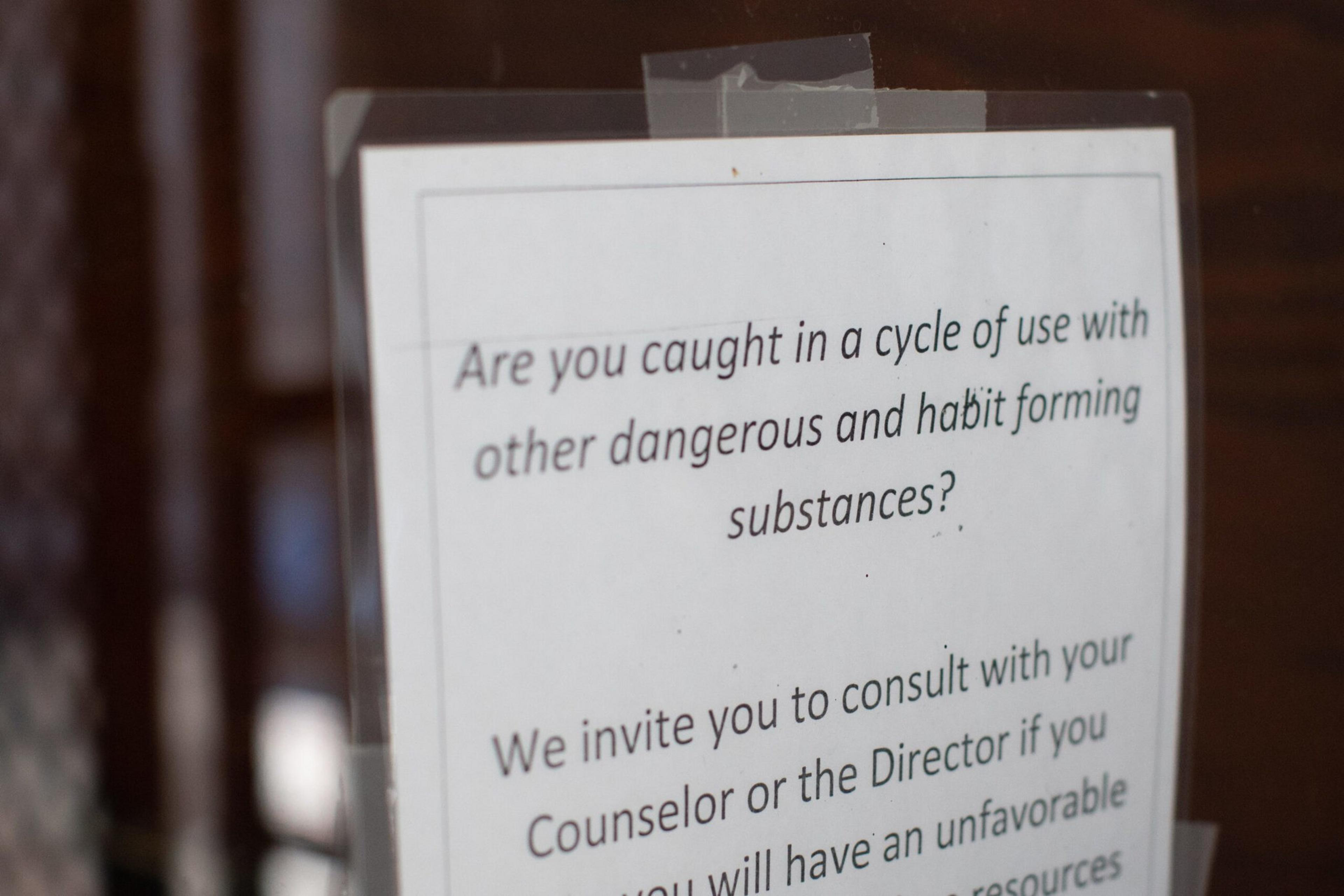

Prospective patients at the city’s methadone clinics must also present photo identification or a hospital bracelet, as well as proof that they suffer from opioid addiction. But because of the potential risk in mixing methadone with other narcotics, patients must also have abstained from drugs for several hours to receive treatment.

“For two people who weren’t high on drugs, it was difficult to navigate,” Robb said. “You’ve got someone who’s nodding out most of the day and they’re supposed to navigate this?”

In a statement, the Department of Public Health acknowledged staffing challenges at behavioral health sites, but wrote that its contracted methadone providers report “no delays in initiation of care.” It reported an average of next day admission to opioid treatment programs, but didn’t respond when asked for more granular detail about wait times at methadone clinics.

However, even a short delay in care can be problematic for drug users fighting an uphill battle against withdrawals or cravings.

Robb said that on Feb. 24, the Bay Area Addiction Research and Treatment (BAART) clinic turned her son away because he had used fentanyl just six hours earlier. He and Robb returned the next day, only to be turned away again because no one was available to do intake. BAART, one of the city’s contracted treatment providers, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

As the city struggles with an overdose crisis that killed more than 600 people last year, reports of delays in care have caught the attention of some policymakers. Supervisor Catherine Stefani plans to call for a hearing about alleged delays in intake at the city’s drug treatment facilities at Tuesday’s Board of Supervisors meeting.

The third time that Robb and Bryan were supposed to meet at the BAART clinic, Bryan didn’t show up. Robb, who lives in Florida, stayed in San Francisco for an extra week looking for her son in the Tenderloin neighborhood. She says he’s since grown more hesitant about treatment, and she wonders how anyone could get clean in the environment her son is in.

“We went out there on our own to look for him and we were pretty horrified. I’ve never seen anything like it,” Robb said. “I don’t know how somebody’s supposed to be able to walk past all of that ridiculousness and decide ‘yeah, I’m gonna stick with the methadone.’”