What are the most dangerous intersections for pedestrians in San Francisco? A local law firm set out to answer that question by looking for the city crossings where people were hit at the highest rate.

Every year, most traffic injuries and deaths occur in the central part of the city where pedestrian and traffic volume is highest. But there are other pockets of the city—like those near highways or on high-speed streets—that are just as dangerous, and where people are getting hit and injured more often on average.

A new study, published by personal injury law firm Walkup, Melodia, Kelley and Schoenberger, examined data collected between 2016 and 2020 by the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Authority and from a 2013 model out of University of California, Berkeley. The study homed in on four intersections—none located in the city’s core—that may be the most dangerous in San Francisco.

The SFMTA has been closely mapping pedestrian injuries and deaths since 2014, when it launched Vision Zero, a program committed to tracking street safety with the ultimate goal of eliminating traffic fatalities in the city entirely. According to the SFMTA’s 2021 severe traffic injury trends report, pedestrians consistently make up the largest group of people hospitalized with either major or life-threatening injuries due to a car crash. In 2020, 12 people were killed while walking in San Francisco. That’s down from 17 in 2019, but still too high, according to Marta Lindsey, communications director for Walk SF, a local street safety advocacy group.

“We should be confident that people are able to cross the street … and not be mowed over,” Lindsey said.

To measure the danger of individual intersections, the Walkup study didn’t just look at the spots with the highest number of people hit. It also looked at intersections with the highest rate of pedestrian collisions per 1 million people crossing at that crosswalk, pulling its pedestrian volume data from a 2013 model developed by SafeTREC, a program at UC Berkeley.

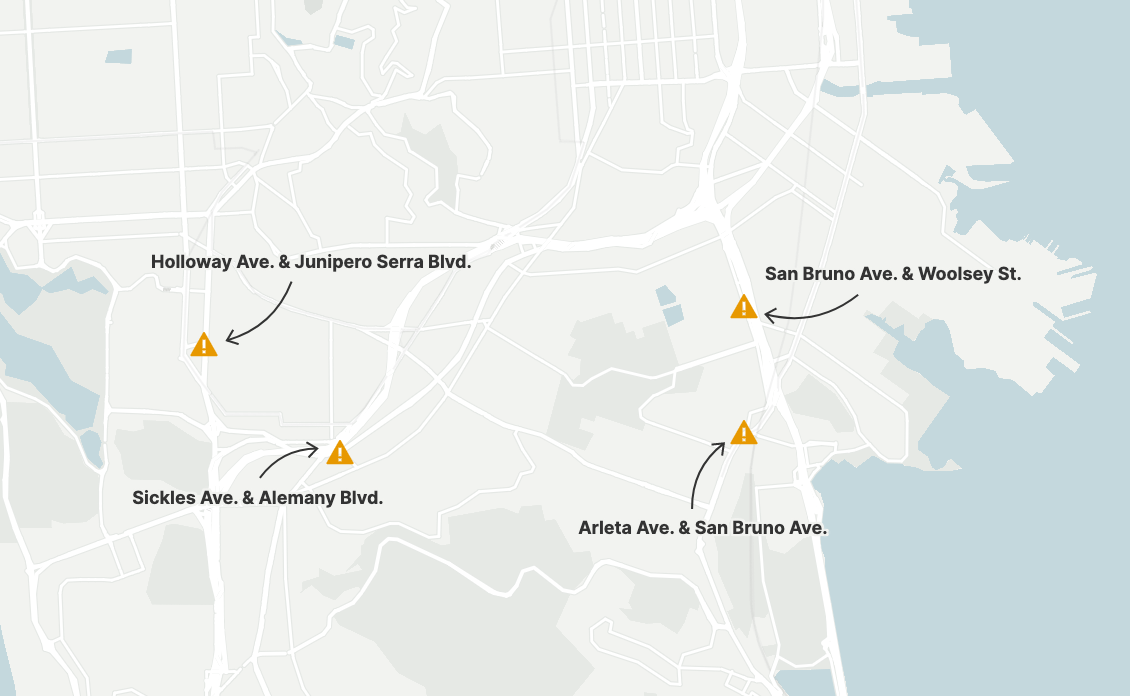

Those numbers led 1Point21 Interactive—the data group that conducted the study—to call out Corona Heights, Candlestick Point, St. Mary’s Park and Diamond Heights as the most dangerous neighborhoods for any given walker. It also allowed the study’s authors to target four intersections—Arleta Avenue and San Bruno Avenue; San Bruno Avenue and Woolsey Street; Sickles Avenue and Alemany Boulevard; and Holloway Avenue and Junipero Serra Boulevard—as particularly dangerous because they land on both the top 20 lists of spots in the city with the highest total number and highest rate of pedestrian collisions.

“By looking at the issue based on pedestrian volume, we can find areas that might actually be more dangerous,” said Brian Beltz, director of content strategy at 1Point21 Interactive.

According to SFMTA, “per million crossings” is not a metric typically used by the agency, as that data can be incomplete or unreliable. And the agency tends to focus more on safety “corridors” by street, not by individual intersection. But Lindsey said it’s an interesting new way of framing the dangers pedestrians face outside of the city’s center.

“We know we’ve got really dangerous intersections in every corner of the city,” Lindsey said.

The study also identified neighborhoods with the highest overall number of pedestrian collisions—the Tenderloin, SoMa, the inner Mission and Downtown. That list looks closer to the ones cited by SFMTA and Walk SF, which did its own study compiling data from 2014 to the start of 2020.

Lindsey said that most pedestrian injuries and deaths happen as a result of too-fast or distracted driving and are not typically the fault of the pedestrian. That’s highlighted in the Walkup study, which found the most common reason for a car-pedestrian collision was a driver who did not yield at a crosswalk.

Some, including Lindsey, had hoped San Francisco would see a dip in fatal crashes in the early days of the Covid lockdown. That didn’t happen, in part because average driving speeds increased, she said.

Lindsey’s group is focused on lowering speed limits, which she contends is the best way to improve safety for pedestrians. Walk SF supports policies like the city’s decision to lower speeds in the Tenderloin to 20 miles per hour on 17 streets and prohibit right turns on red at 54 intersections. Assembly Bill 43, which passed at the end of 2021, gave the city more control over speed limits and could extend similar measures in other neighborhoods.

SFMTA has also been working to improve the four intersections highlighted in the Walkup report by widening sidewalks, re-striping crosswalks, removing parking, adding pedestrian signals and lowering driving speeds—and said it’s no surprise these corridors, which were originally designed for high car speeds, made the top lists.

Smart street design is another way to reduce crashes, Lindsey said, noting that improving left-hand-turn safety is low-hanging fruit. Left turns accounted for 40% of pedestrian traffic deaths in 2019, according to data from the SFMTA, and the agency plans to add vertical posts, speed bumps or paint to encourage slow and wide left turns at 35 intersections by 2024. But Lindsey said she’d like to see that program and others expanded even further.

“People think this couldn’t happen to them or to their loved ones,” Lindsey said. “The sad truth is that it absolutely could.”