Bay Area Rapid Transit opened for passenger service 50 years ago this weekend, on Monday, Sept. 11, 1972. Capable of running at speeds of up to 80 miles per hour and with lead cars whose shape evoked the nose cone of a NASA rocket, BART was the first major transit network to debut in the United States since the 1920s.

Opening day was momentous, and veteran journalist David Louie (opens in new tab) of ABC-7 KGO was there to cover it. Or, rather, since he was working the night shift in those days, he clocked in roughly two hours after Oakland Mayor Frank Ogawa and San Francisco Mayor Joe Alioto held a ribbon-cutting ceremony at Lake Merritt Station.

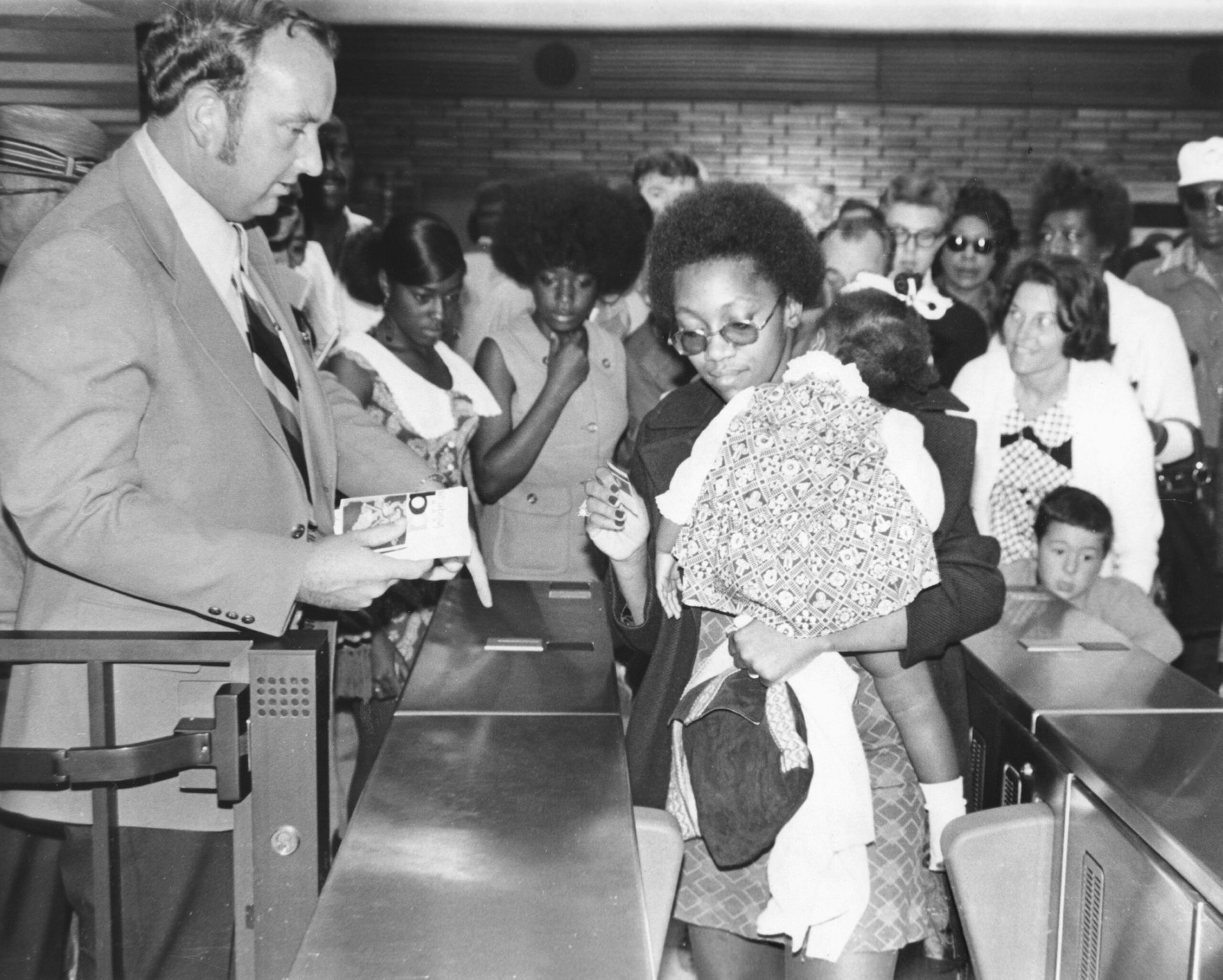

“They opened for revenue service at 12 noon, and it was packed,” Louie recalled. “They had long lines at the turnstiles because no one was familiar with the ticket system: a little piece of paper with a mag strip on it. There were no glitches. It was smooth, but people were a little hesitant.”

The minimum fare at the time was only 30-cents. Louie recalls that the first ride was standing-room only, which BART was “never designed to be.”

“The key thing about the era was they had no hand straps or handles to grab onto, because it was designed to be a system where everybody had a seat. I believe the capacity was 72 seats in the cars,” he says, adding that engineers designed the trains “to lure people out of their cars with nice wide, upholstered seats—and carpeting.”

The fastest transit system in the world at the time, BART was undeniably forward-looking. However, nobody rode into San Francisco that day, as the first line to open ran entirely within the East Bay, between Fremont and MacArthur Station in Oakland. It wouldn’t be until December 1973, more than a year later, when BART finally delivered riders under the Bay and into San Francisco. Read up on a full history of BART, past to present, here (opens in new tab).

While the era is synonymous with urban decline, San Francisco saw major changes to its urban fabric. BART, the Transamerica Pyramid and Sutro Tower all opened within an 18-month period—plus the region got its second Asian American TV journalist, a young transplant from Cleveland.

“I came to the Bay Area in 1972, right out of university. Sutro was under construction right up to the ‘waist’ level, where it tapers,” Louie says. “Traffic was not all that bad in those days, but as we know when you look at the history of BART, they had a vision 20 years earlier to create a regional system. There would be growth in the East Bay in particular and we had to find a better way to get people from Point A to Point B.”

Planning for BART began as early as 1957, but the development of a regional system was anything but linear. Only a year later, the Key System (opens in new tab) tracks were ripped out of the Bay Bridge, ushering in a 15-year period when you couldn’t cross the Bay by rail at all. Marin and San Mateo counties were supposed to join BART, but transit authorities responsible for the Golden Gate Bridge looked askance at the idea of adding a second deck for trains to run on.

And for all its Space Age aspirations, BART remains an outlier in public transit. Aside from perceived challenges with cleanliness and disorder, BART’s problems are structural. Tunnel clearances are low. The tracks use a different rail gauge (which is to say, width) from virtually all other systems. Fare coordination with other public-transit systems is poor to nonexistent. A lack of passing tracks means one temporarily disabled train may generate cascading delays down the line. When the system goes down, it goes down hard.

“Some of the things that they got wrong, they got so wrong that they’re kind of existential. You couldn’t really fix them,” says Tom Radulovich, executive director of the nonprofit Livable City and a former BART director. “BART was an engineering experiment. But nobody followed BART.”

Designed to meet the needs of the mid-20th century Chamber of Commerce and other proverbial powers-that-be, BART is a product of 1950s planning. Specifically, it largely exists to funnel white-collar suburban-dwellers into San Francisco’s office core—a less essential function amid the rise of remote and hybrid workplaces.

It only has eight stations in San Francisco, too. The Washington Metro, the system which Radulovich says resembles BART the most, has more than three times as many stations within the District of Columbia. And because BART’s suburban stations are often located in freeway medians surrounded by giant parking fields, they’re less useful when going to, say, Downtown Pleasanton. But the trains themselves have what Radulovich calls “moon-landing bling.”

Janice Li, a current BART board member, is likewise resigned to BART’s “space-y, aluminum-body rail cars.” She compares the system’s designers to people who doubled down on Blu-ray in the age of DVDs, and today’s maintenance workers have to come up with creative workarounds to solve any problems that emerge.

“So much of the BART system is incredibly bespoke,” Li says. “Visiting the shops is one of my favorite things to do. They were showing me a device used to test a very particular component that someone had to build from scratch in the ’70s, because whatever component BART had is so unique, there was no way to test it.”

Li, like David Louie, plans to attend the celebrations at Lake Merritt on Sunday, half a century after the beleaguered transit system’s optimistic debut. She says will be thinking about the original vision of a full ring around the Bay, and is conscious that the decisions she and her colleagues make will have repercussions decades hence.

“I’m going to be there to hear some speeches,” she says. “But I really want to stop at Powell and play the arcades (opens in new tab).”