The World Cup is upon us, America has its most talented team since ever, and in four short years, the World Cup will be right here in the Bay Area. But in SF, one of the world’s richest sports markets, we don’t have a team. The Standard found out why.

It’s 2022, but attending a soccer match in San Francisco still feels very much like a journey back in time—the people have changed, but the places are the same.

Think of the Warriors’ Chase Center, which opened in 2019, as a sort of modern spaceship. It comes complete with luxury suites, generating millions in revenue, shopping and Wi-Fi on every floor.

That would make Kezar Stadium—still home to some of San Francisco’s most prominent soccer teams—sort of like Rome’s Colosseum, a beautiful relic of the past stashed inside a city that’s modernizing all around it.

Kezar first opened in 1925, costing $300,000—roughly $5 million in today’s money. It’s a modest sum if you consider the price of developing anything in San Francisco these days, which almost always runs in the millions and is near impossible to do.

The stadium is still situated in the heart of San Francisco. Back when the 49ers played there until 1970, it seated 60,000.

In 1989, the stadium was torn down and rebuilt to a much smaller capacity of 10,000. Today, it serves as a convenient venue for a mix of prep, amateur and recreational sports leagues, with soccer regularly played at Kezar.

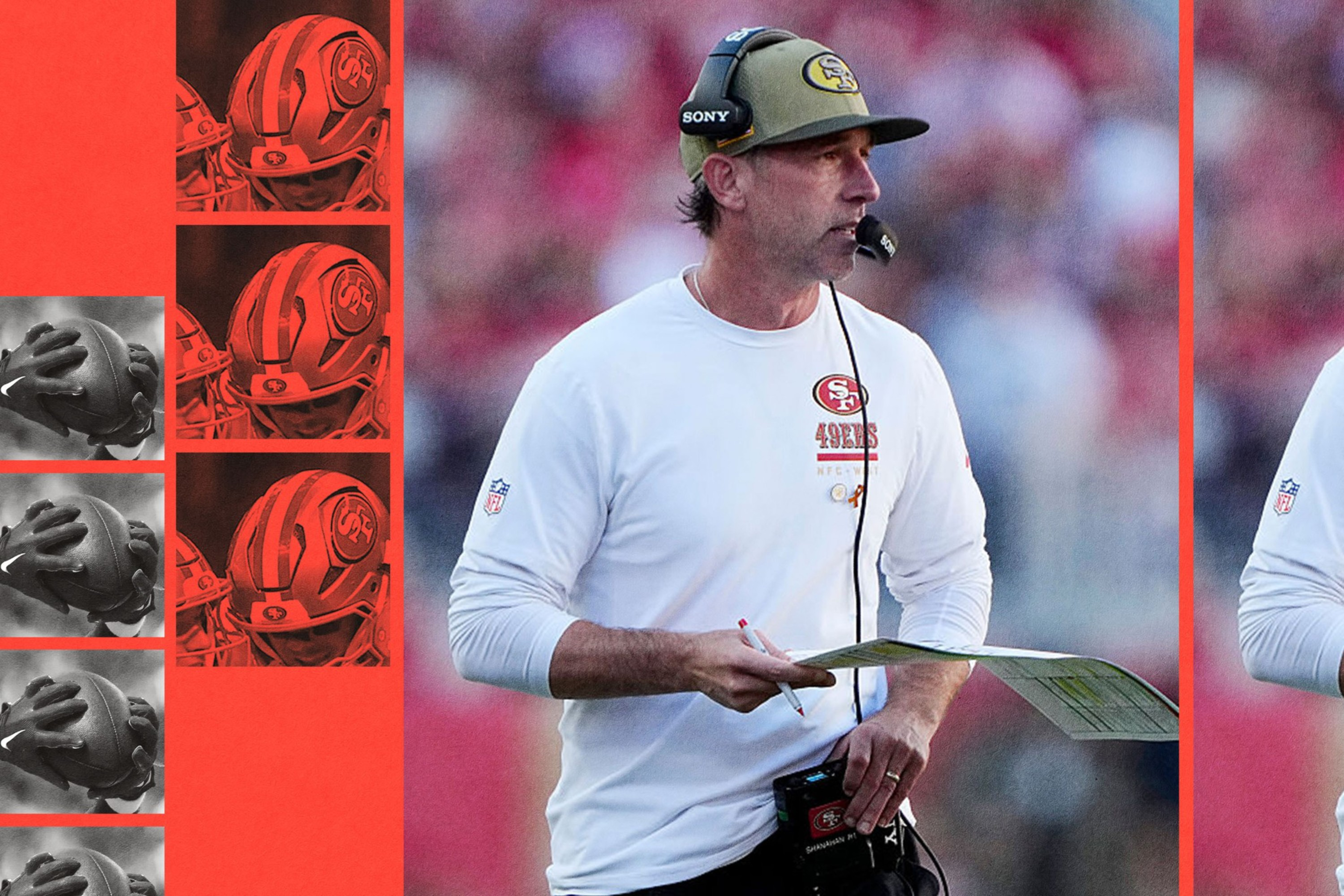

Section 415: Brock Purdy, Mac Jones, and the 49ers’ path to the playoffs

Section 415: Making sense of the Warriors’ uneven start

Section 415: How Natalie Nakase turned the Valkyries into an immediate force

So it has the infrastructure for a professional team.

Yet, the nearest professional soccer team, the San Jose Earthquakes, lies 50 miles away. The Earthquakes’ PayPal Park holds 18,000 and boasts the “largest outdoor bar in North America.”

Of course, San Franciscans can get their professional sports fix with the Warriors and Giants on the city’s east side.

But ahead of the world’s most popular sport dominating the airwaves for the next four weeks, why is a global city like San Francisco—one of the richest sports markets in the country—completely off the grid when it comes to the “beautiful game”?

The history is telling.

Last in SF, but No. 1 in SJ

San Franciscans have long heard the reasons why major league teams pass up on the city.

In 1974—and stop me if you’ve heard this already—professional soccer was one of the fastest-growing sports in the U.S. So much so that the championship game between the Los Angeles Aztecs and the Miami Toros (opens in new tab) of the North American Soccer League (NASL) was televised live on major network CBS. (For reference, NBA playoff games were regularly shown on tape delay (opens in new tab) during the ‘70s and ‘80s on the same network.)

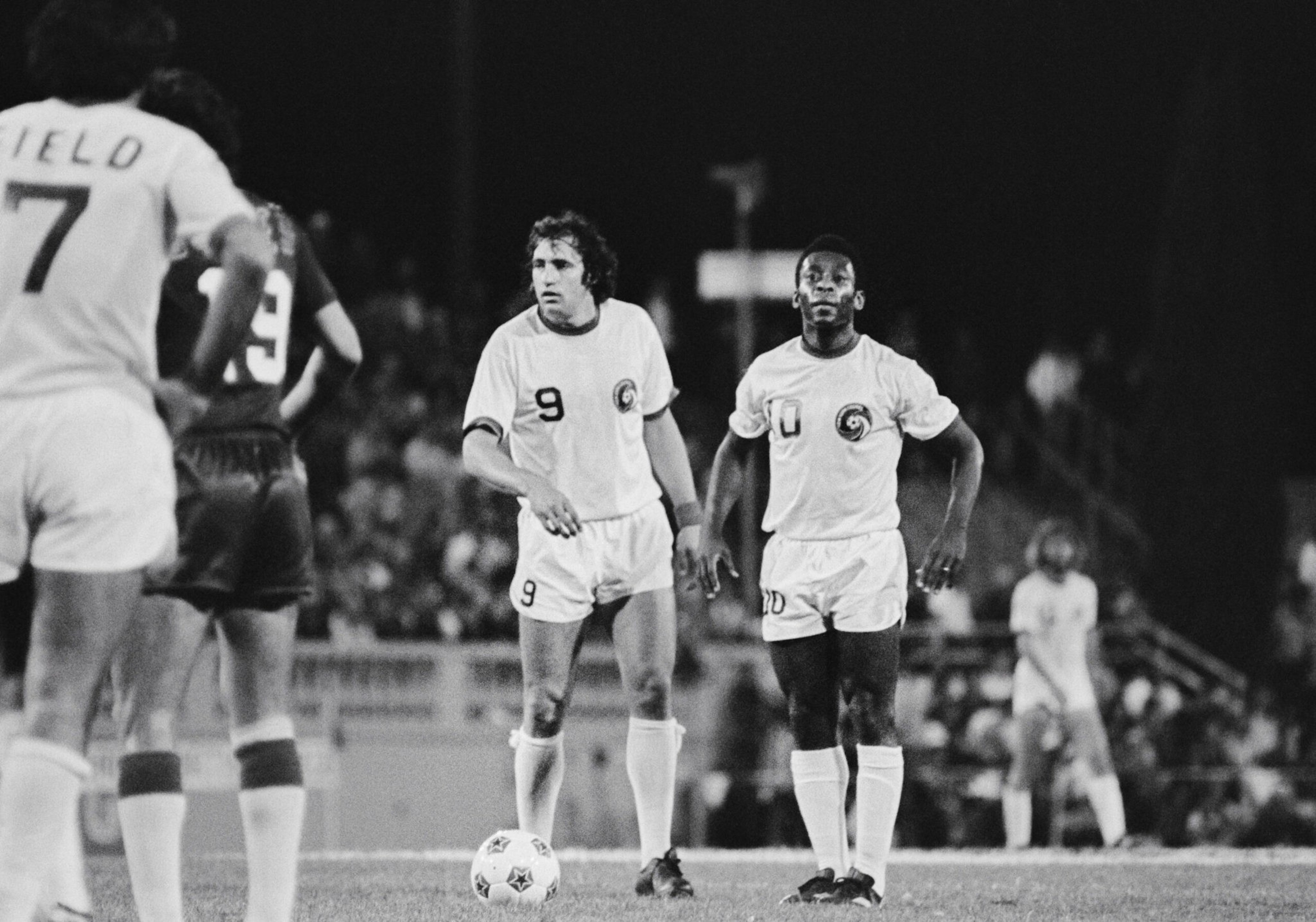

Buoyed by that momentum and the anticipated arrival of global soccer icons such as Pelé (1975), George Best (1976), Franz Beckenbauer (1977) and Johan Cruyff (1978), the NASL, then the top-flight American soccer league, pushed for further expansion into the West Coast.

Seattle and Vancouver quickly nailed down spots that remain until this day. For Northern California, the established owners in the NASL assumed a new team in San Francisco or Oakland would represent the market as it had done in other major sports.

But Milan Mandarić, then a 35-year-old immigrant from the former Yugoslavia—who made a small fortune running an electrical components firm in San Jose—had other plans when he bought into the league.

After outbidding two other parties, Mandarić founded the San Jose Earthquakes, the city’s first-ever professional sports team.

“The reason I insisted that the club be located in San Jose was that there are too many major league clubs in San Francisco, and the people in San Francisco are blasé,” Mandarić’s general manager Dick Berg told Sports Illustrated in 1974 (opens in new tab) after the Quakes set the highest attendance mark in NASL in just their first year.

“In the San Jose area, there are a million-and-a-half people looking for something like this,” Berg said. “I didn’t want us to be the last team in San Francisco. I wanted this club to be No. 1 (in San Jose). And it is.”

Even though the NASL eventually folded in 1984, the weight of that history carried over when professional soccer in the U.S. was revived 10 years later—under the banner of Major League Soccer (MLS), the top-flight league that operates today. With it came the return of the San Jose team, too, albeit with new owners, which also hosted the league’s inaugural match in 1996.

And there in the South Bay, top-flight soccer in Northern California has remained, complete with a new soccer-specific stadium (Paypal Park) built in 2015 and generations of fans to fill it.

Even if a San Francisco group wanted to join the MLS today, there isn’t exactly an open invitation to do so.

In 2019, Carolina Panthers owner David Tepper paid $325 million (opens in new tab) into MLS just for permission to start developing the league’s 28th team—Charlotte FC. That’s before factoring in the costs of building or renovating a stadium, which the league requires, and recruiting and paying for players and staff.

The 49ers had to answer some of the same questions in the late 2000s when the team explored a new home after 40-plus years at Candlestick Park. They found that the land, money and political will in SF were suddenly in short supply.

In other words, the MLS ship sailed a long time ago. And it would take an obscene amount of money to see it again.

Won and Done

Whereas the flight from Kezar and Candlestick signaled a turning point for major football and soccer teams, the explosion of the tech industry in the Bay Area from the late ’80s into the 2010s brought unprecedented wealth and talent into SF.

With that, came the development of technology and products that have changed the world forever.

In 2015, Brian Helmick hoped to parlay some of that momentum into a new professional soccer team he called the San Francisco Deltas. As of publication, they would be the city’s last.

Without any interest from MLS, the former tech company CEO tried to Silicon Valley his way into making professional soccer work in SF.

The Deltas debuted in the new NASL in 2017, spending big on top players and staff, luring them away with a plan to lead the game in an untapped global city.

To round out their offering, the Deltas also spent $500,000 on apartments for players and their families in Nob Hill.

They went on to play home games at none other than Kezar Stadium, which by now had a capacity of 10,000 seats. For the opening game, the Deltas drew roughly 4,400 fans. That number plummeted to 1,739 by game two.

“It’s no secret that SF is not a cheap city,” former Deltas president Todd Dunivant told The Standard. “We weren’t making as much as we hoped for at the gates, which meant we were going deeper into the red every single game. And that’s before even paying a salary to the players and staff.”

Even though Helmick made a midseason plea for San Franciscans to save the Deltas from “drowning (opens in new tab),” attendance lagged all season. Combined with the fact that the new NASL was at risk of dissolving because of an accreditation dispute (opens in new tab), the players learned midseason that the Deltas experiment would only last one year.

They went on to see success on the field despite everything going wrong off of it. In their lone season, the Deltas remarkably qualified for and won the last-ever NASL final at home against the storied New York Cosmos.

“I’ll never forget that championship game,” said Dunivant ,who is now the team president of Sacramento Republic FC. “Kezar is magical when it is filled like that. There’s not a lot of places like it—located in the heart of a city—in this country. I think that night really showed what San Francisco soccer is capable of.”

Delta’s tickets sold for around $30 that season. But for their final game, the team lowered the price to $5 a seat. For the first and only time in their brief history, the Deltas sold every ticket and fans celebrated on the field (opens in new tab) with the team after the final whistle.

Shortly after, the Deltas closed up shop (opens in new tab).

The Race To Be the Face of SF

“Just labeling a team ‘San Francisco’ is not enough for it to stick in this town,” said Joachim Steinberg, a board member of the semi-pro, fan-owned-and-operated San Francisco City Football Club.

Steinberg, a lawyer from New York by way of Detroit, discovered SF City FC during one of their games at—you guessed it—Kezar Stadium. He said he fell in love with the venue and the team’s passionate supporters and soon signed up as a member.

Contrary to the Deltas or MLS expansion ethos of fronting loads of cash, the SF City FC ownership group is set up so private investors can only own up to 49% of the club, meaning fans will always have the final say on matters.

“If the membership decides that it’s comfortable being an amateur club, then that’s what we’ll do,” Steinberg explained. “But if they want us to make a run at being a top-flight team, then that’s what we should do as well. What’s important is that we do what the community wants, rather than someone parachuting in and attempting to subsidize high-level soccer off the backs of youth soccer.”

Steinberg said the club’s priorities are to keep expanding membership, hopefully reaching 10,000 one day, which is also enough to fill Kezar Stadium. With such momentum, he hopes that SF City FC can go fully professional by the time the next World Cup comes to the Bay Area in 2026.

But the path to that dream is not without obstacles—or competition.

For one thing, the pandemic canceled two years worth of soccer, which Steinberg acknowledged set the club back.

SF City’s quest for 10,000 members has also been complicated by the fact that another San Francisco team, the SF Glens, got a head start on their quest to bring professional soccer to the city.

As opposed to their crosstown rivals, the Glens trace their roots to an Irish American amateur team founded in 1961. They have since developed one of San Francisco’s larger and more well-respected youth soccer academies. But until recently, their adult teams were all still rooted in the amateur leagues.

Current executive director and general manager Mike McNeill said he discovered the Glens in 2011 after injuries derailed his college soccer career. From that setback, he pivoted to coaching full-time, bouncing between the high school game and volunteering with the Glens’ youth teams.

That’s when he noticed a gaping void in the SF soccer ecosystem.

“I would describe the [soccer] scene back then as dormant or limited at best,” McNeil recalled. “The best players were leaving San Francisco because there wasn’t that much opportunity here.”

By 2018, the spectacular fall of the aforementioned SF Deltas left an opening—one that McNeill said the Glens were uniquely positioned to capitalize on because of their unique brand and history.

He presented to the Glens’ ownership group a five-year strategy he felt would push them to the top of the pecking order in SF soccer. In no particular order, the plan entailed:

Establishing a new first team that players within the organization could aspire to. Connecting youth teams to the best competition and scouts. Getting a new soccer-specific stadium built. Turning the Glens pro.

The year McNeil pitched his ambitious proposal coincided with the World Cup being held in Russia. While watching the tournament at the Kezar Pub, the famous sports bar across the street from the stadium, he met Jimmy Conrad, who was doing man-on-the-street media work for Qatari network beIN SPORTS.

Conrad is a soccer celebrity of sorts. He vlogs, pods, hosts and posts about the game online and on TV. But more importantly, he played 13 years in the MLS and reached one of the sport’s greatest pinnacles when he made the U.S. team at the 2006 World Cup in Germany. He retired in 2011 and moved with his young family to Marin, where he pursued his coaching licenses and burgeoning media career.

McNeil approached him at the pub that day with a proposition: You live here, so help us build the next pro soccer team in SF. By the end of that summer, Conrad was announced as the Glen’s new technical director and associate head coach of the first team.

“There’s a level of interest that having someone like [Conrad] brings to our club,” McNeill said. “On top of the experience at the highest levels of the game, he’s also opened so many doors for us, where without him, it might have taken three or four calls to get a meeting.”

For Conrad, the fit with the Glens was a bit more personal.

“I was a walk-on in college who was told I wasn’t good enough to play, and that continued all the way to the national team,” Conrad said. “I’ve heard that sort of stuff my entire life, yet I kept pushing forward somehow. So if I can motivate kids to believe in themselves the way I did, that is something I want to do.”

He also has strong views on how youth development should be handled in SF.

“Is it about doing what’s best for the kid or is it just about making money?” Conrad asked. “Sometimes that dynamic can handcuff the development of a talented player. I’m a believer that if we can’t yet provide what that kid needs, that we should try to move them on to a place that can. It’s about giving people opportunities that they otherwise wouldn’t have.”

Treasure Island: ‘A Shining Jewel’

Four years have passed since McNeil unveiled his bold five-year plan, and from the outside, it would appear the Glens have pulled ahead in the race to become the next face of pro soccer in SF.

In the first three years, the Glens made good on creating more pathways for their players to go pro. Their first team now competes in the semi-professional USL League Two instead of the amateur Sunday leagues, although they still compete there, too, with other squads. (Note: SF City had been competing in USL League Two earlier.)

Later in 2021, they also became the first team in SF to join MLS NEXT, the nation’s premier youth soccer competition, ensuring that academy players get a chance to compete against and in front of the best in the country every year.

But the biggest step toward legitimacy came in September when the team broke ground on a new Treasure Island (opens in new tab) soccer facility. The project will feature a 1,500-seat waterfront stadium built to FIFA-regulations and will include two smaller fields for training.

Mayor London Breed showed up for the groundbreaking ceremony and threw her support behind the Glens.

“When [the World Cup] comes to the Bay Area in 2026, this field is going to be the shining jewel,” she said at a press conference (opens in new tab). “This is going to put San Francisco officially on the map in the soccer world like nothing else.”

But one last item on the five-year plan remains: making the Glens a fully professional team.

Without the MLS—an enclosed league with limited space and a high barrier to entry—their best shot will be to join the second division United Soccer League Championship (USL) like their Northern California neighbors Oakland Roots and Sacramento Republic, which found that being in the “minor leagues” doesn’t really affect support (opens in new tab).

Until then, the Glens and their rivals SF City might disagree on how to reach that destination, but their revelations about building something that lasts are the same. In SF, it’s got to be built from the ground up, rather than top-down.

Editor’s Note: The FIFA Men’s World Cup, hosted by Qatar, kicks off on Sunday and will run through Dec. 18. For the duration of the tournament, The Standard will explore a series of soccer stories through a Bay Area lens.

The games will be televised on the FOX network and FS1 (English-language) and Telemundo (Spanish-language). If you’re in the city, view our San Francisco Where To Watch the Games Guide here or check out the World Cup Village downtown.