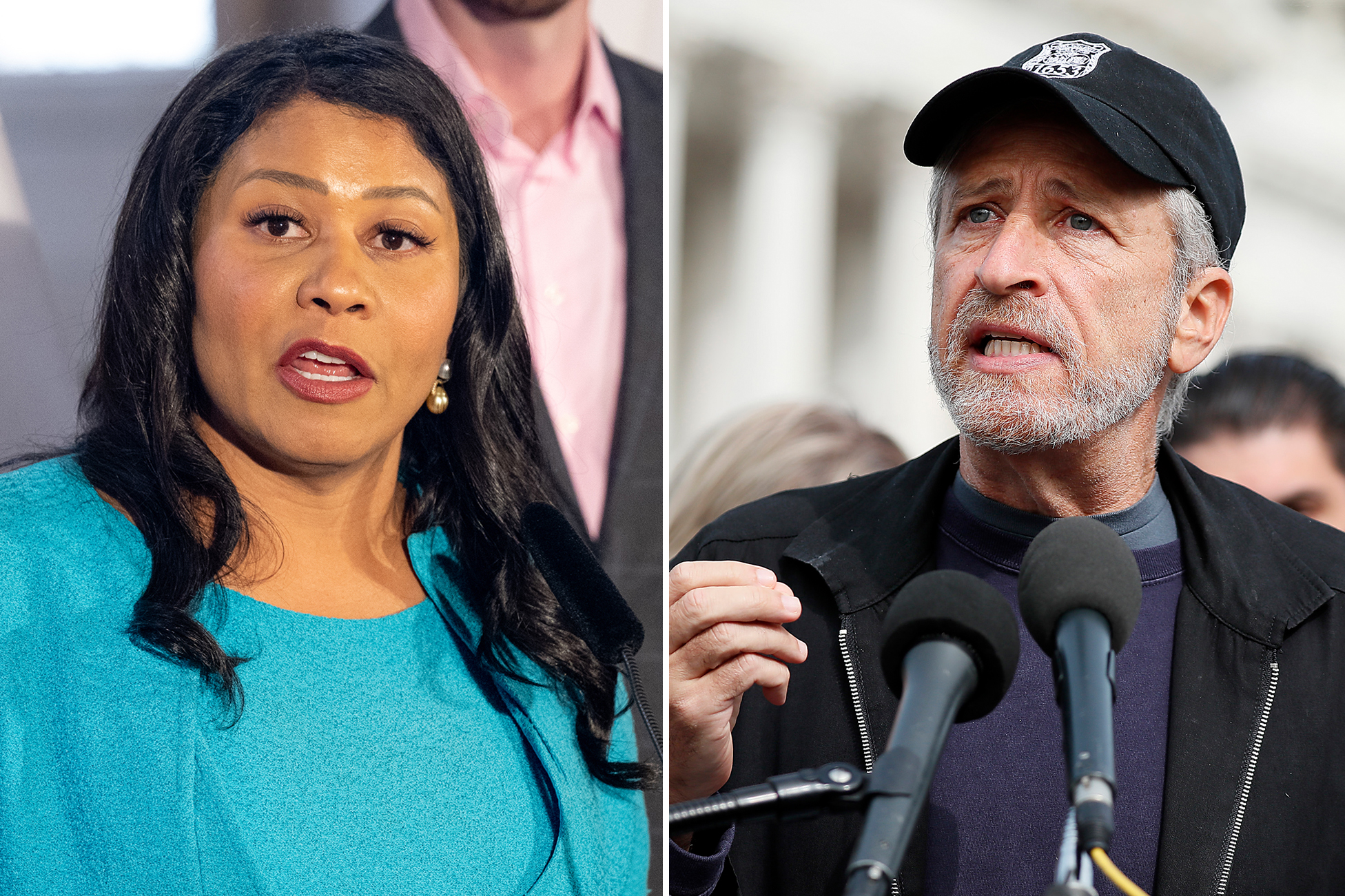

On his podcast “The Problem,” Jon Stewart got a surprising response when he asked Mayor London Breed about her approach to fixing the city’s issues.

The comedian asked Breed whether she’s seen a particularly promising system for bringing back folks struggling with mental health issues or addiction.

“Not necessarily,” Breed replied. Stewart took it as an honest admission of the difficult problems at play.

In the interview, Breed discussed how her upbringing colored her approach to criminal justice, her problem with San Francisco’s stated progressives and where she thinks the city is handcuffed in its ability to deal with the intertwined crises of mental health and homelessness.

Stewart, who also shared memories of playing at the Punchline after the Loma Prieta earthquake—when a visible crack adorned the comedy club’s walls—introduced Breed as “criticized, I think, by everybody, for being too soft on crime, too tough on crime.”

Breed, who grew up in public housing and whose family was deeply impacted by addiction and the criminal justice system, credited her grandmother with helping her survive that gauntlet. She said it was her upbringing that has shaped her views on public safety and drug addiction.

Breed described her grandmother as “really hardcore” and posited that she was harder on her than her brothers. That meant Breed “had to do all the chores, run her errands, pay the rent” in an early lesson on accountability.

“You were saved by sexism?” Stewart joked.

The conversation touched on Breed’s frustration with progressivism as it is conceived in San Francisco. The mayor took the opportunity to voice some of her regular criticism of the Board of Supervisors.

“There are members of that body who feel that they are the carriers of the torch for progressive values in San Francisco,” Breed said.

“To be clear, these are people who don’t know what it feels like to live in these conditions, and they are constantly pushing against the recommendations that are being even made by the people who are living in the conditions that are so frustrating,” she added.

On this week’s podcast, we talked to @SFGov Mayor @LondonBreed about what it’s like to lead a city through spikes in crime and homelessness. Listen to the full episode now on @ApplePodcasts. https://t.co/ud5ysvNEPr pic.twitter.com/femre9H5Xt

— The Problem With Jon Stewart (@TheProblem) March 29, 2023

When trying to parse out intersecting issues impacting the city, Breed drew a straight line between homelessness and substance abuse and touted the need for safe consumption sites and a “tiered” system of addiction programs.

“The problem is, of course, the behavior and the challenges that exist from my perspective from a lot of the use of drugs and the psychosis that happens as a result of the use of drugs,” Breed said. “Oftentimes, that’s not reversible. So we have people who are more erratic, people who are more combative, people who are more engaged in the kind of behavior where people are afraid.”

In line with that take, Breed pushed for more tools to compel people into treatment if they are unable or unwilling to do so voluntarily. Earlier this month, Breed joined a coalition of lawmakers in pushing for updates to California’s conservatorship laws.

“We have to have a level of force associated with that to really get people on the right path,” Breed said. “If you have mental illness and you’re out on the streets and you’re walking in and out of traffic, you know, we can do a 72-hour hold. But through our legal system, if you say, I’m okay and you want to go back on the streets, you are allowed to do that.”

She used the example of an older woman who walks around naked, dragging a blanket behind her, who becomes violent when approached.

“The only thing we can do is detain her. She goes through the process, and she says ‘I’m okay. I can take care of myself.’ And that is not a solution,” Breed said. “That is doing the same thing over and over, expecting to get a different result, which we will not get unless we’re willing to put in a level of force that sometimes also makes people uncomfortable.”

“When we’re trying to change the policies, we start talking about [forcing] someone into treatment. Then all of a sudden, people are like, ‘Well, wait a minute, conservatorship. Look at what happened with Britney Spears. We don’t wanna take away someone’s rights.’”

“If it were me, I would want someone to force me into whatever treatment possible,” Breed said.

Part of the problem, Stewart pointed out, is a lack of available treatment beds.

Breed said she believed that resources could be diverted from jails and prisons into “mental health facilities that could meet the needs of those suffering from schizophrenia or dementia or issues where they can’t necessarily take care of themselves.”

As for why San Francisco has become such an avatar for urban decline? Breed pointed the finger at President Donald Trump, who turned the liberal city into a useful foil, as well as social media, which can create viral moments that take hold in the popular imagination.

“I think people see those videos and think, ‘Oh my goodness, San Francisco is such a scary place,” Breed said.

One of the most striking aspects of the interview was the clear admission by Breed of the limited impact that an individual city like San Francisco can make in tackling its problems of homelessness and drug abuse.

“I think what we’re doing in San Francisco is trying to stop the bleeding,” Breed said. “We can’t do this alone. We can’t arrest our way out of this problem. We can’t get enough people into treatment to make a dent.”