A grand plaza is meant to be the beating heart of a city, the core from which important civic functions radiate. San Francisco’s United Nations Plaza was dedicated in 1976 in honor of the international peacekeeping body, whose 1945 charter was signed around the corner on the stage of the Herbst Theatre.

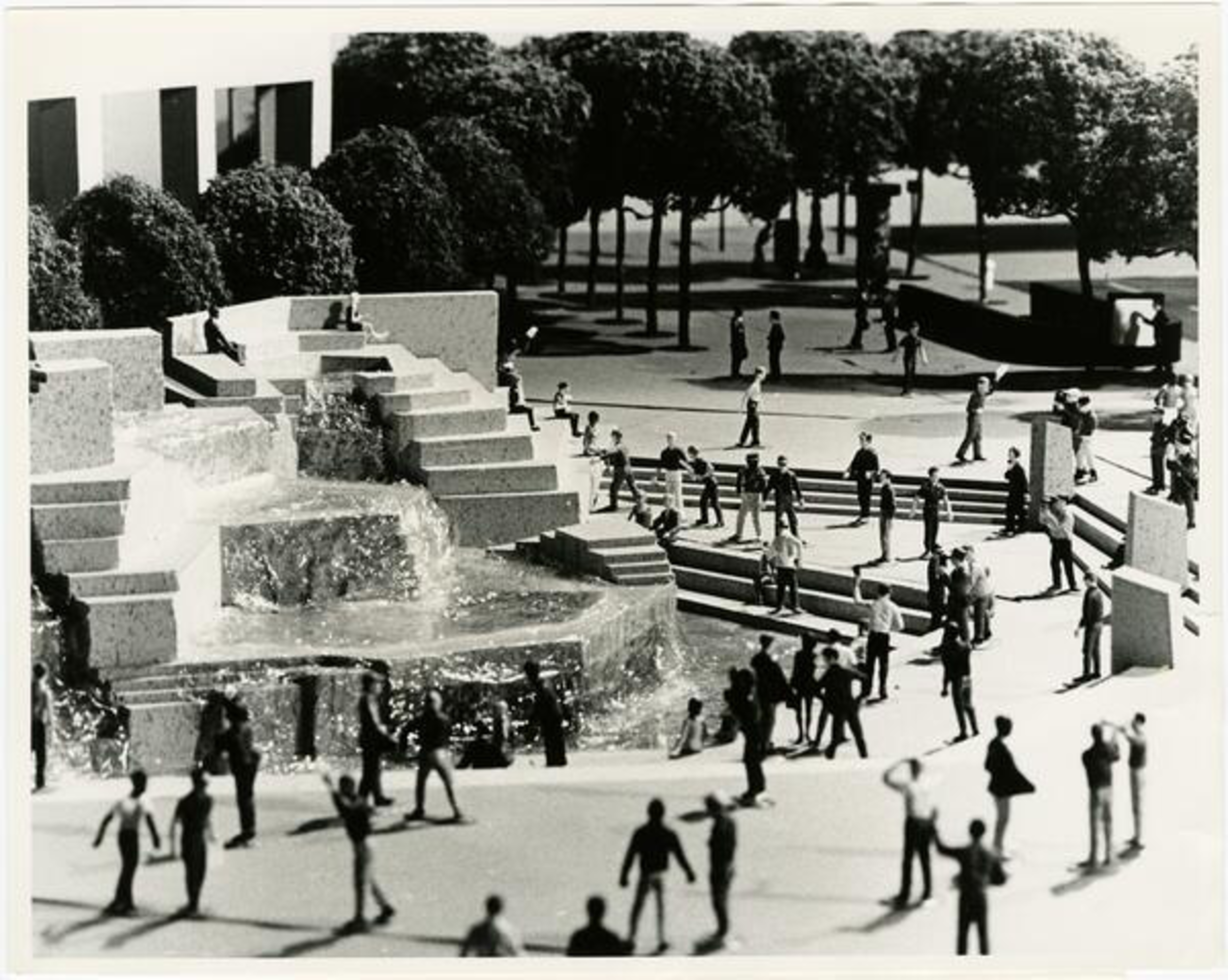

The plaza’s planners, Market Street Joint Venture Architects, intended it not only as a pedestrian passage and a nod to the U.N. but also as an “open space amenity for shoppers, office workers, students and visitors,” according to its architectural plan.

But the U.N. Plaza of today, even with the elegant dome of City Hall in its sightline, is not a source of civic pride. It’s neither a welcome mat nor a beating heart. Blue spray paint mars the underside of the Simón Bolívar statue, the once-gurgling fountain is covered in graffiti and bird poop, and the columns in honor of U.N. member states have text that has almost completely worn away.

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that the area has become a ground zero for drug dealers and a marketplace for stolen goods—and the site for a proposed Board of Supervisors meeting, where Mayor London Breed could be heckled about her response to the fentanyl crisis on the very physical location where it’s unfolding.

Yet the controversy around U.N. Plaza is not new, and it tends to pool around the area’s central feature: the fountain.

The Sierra granite fountain is the figurative heart of the heart—where pools of water mimicking the tides used to flow. The granite pieces comprising the fountain weigh more than 3 million pounds and are layered in groups to represent the continents of the earth, with each mass tied together by pools symbolizing the oceans.

But even before construction was complete, the fountain was an overflowing source of controversy.

“The art commission did not like it from Day One,” said longtime civic leader James Haas, who authored a book on San Francisco Civic Center’s design (opens in new tab).

In 1974, the San Francisco Arts Commission adopted, then dropped, then re-adopted plans to approve the fountain. Then-Supervisor Quentin Kopp called it an “architectural travesty” and an “environmental insult.” Others complained about the cost.

People used words like “flamboyant” and “vulgar” to describe the fountain, attributing it to the oversized ego of the (very famous) landscape architect who designed it, Lawrence Halprin (he also designed the fountain at Levi’s Plaza). Famed local artist Ruth Asawa called it brutal, saying it was not designed for people. But Halprin was steadfast in defending his creation—saying it was people-oriented and modern.

The only concession he made to critics was removing from the design 20-foot-tall granite blocks that were going to surround the fountain, Haas said.

There have been additions to U.N. Plaza since its construction, too. In honor of the 50th anniversary of the U.N., the area was refurbished in 1995 with new light fixtures, an engraving of the preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (opens in new tab) and excerpts from the U.N.’s charter inlaid in brass.

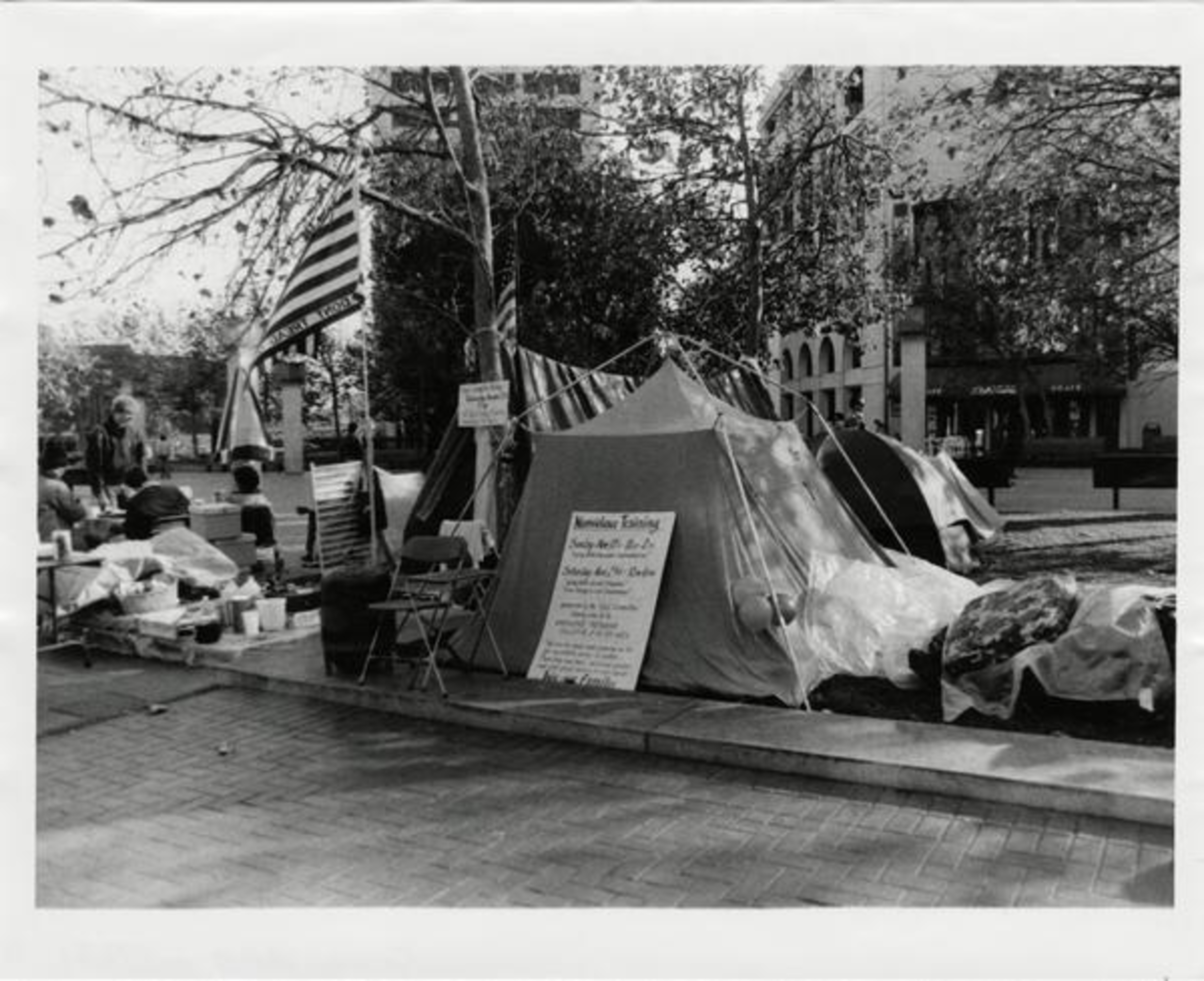

In the early 2000s, there was a plan to take out the fountain, which had by then attracted people using it as a restroom and a bathing area. It “became a public toilet, shower, washing machine, brothel, garbage can and drug market all in one,” The New York Times wrote (opens in new tab) in 2004, tsking about San Francisco’s foibles then as now.

But those plans were squashed. Instead, “no trespassing” signs and chains dangling from concrete tubs were added around the perimeter, the first in a long line of ineffectual attempts to protect the fountain. The area has since been cordoned off by everything from bollards to metal, plywood to plastic. Its most charming enclosure was perhaps this white lattice fence (opens in new tab) from 2019.

Today, the fountain is surrounded by metal fencing, and drug use and lawlessness in the plaza have again prompted some to call for its complete closure (opens in new tab). Halprin’s (opens in new tab) creation, which was intended to be the focal point for the plaza, has turned into its eyesore.

“It became a horror show,” Haas said of the plaza. “And the city made it worse by putting the Tenderloin Linkage Center there.” Breed opened the center as a strategy to combat the fentanyl crisis, but it immediately came under criticism as a de facto safe-consumption site that did not end up connecting people to services (the center closed down at the end of 2022).

Walking through the plaza in the early afternoon, the space is mostly empty. There are cleaning trucks and a mobile San Francisco Police Department unit. A few people hawk what appear to be stolen goods out of a reusable shopping bag, and another person looks to sell drugs.

Lines from the United Nations charter are inlaid into the pavement, including an idea about “the promotion of the economic and social development of all peoples.”

A few people stand by the fountain, watching the pigeons congregate as “California Dreamin’” blasts from a nearby speaker. A man tosses pieces of bread to the birds. When a woman with long brown hair and tawny-colored moon boots nudges open the metal fencing surrounding the fountain with her foot, everyone watches to see what she will do.

She bends in front of the granite slab and slides her backpack off her shoulders, pulling something from the inside. When she stands up to walk away, it becomes clear what it is—a dead bird. Its motionless white feathers and talons stick up to the sky on the lowest slab of granite, the one that’s meant to symbolize the lost continent.