With a bemused smile, Ocean Escalanti took in the swirling maelstrom of several hundred curious, hungry visitors at Sunday’s San Francisco Zine Fest.

One of Escalanti’s zines, “Moving House,” is a collection of her poems. Another, “Fortuna,” is made of found photos, collections abandoned by strangers or encountered in thrift shops.

Escalanti and her partner, Jasmine Djavahery, and other members of Berkeley’s Tiny Splendor Press also displayed stickers and Risograph prints at their booths. On cardboard, they had printed a handwritten price list with items from $2 to $20, although trade among vendors is commonplace.

“I think it’s a really affordable, accessible way to exchange art and also open up accessible art to the community,” said Escalanti, a former printmaking major who got involved after taking a zine class at the San Francisco Art Institute.

She reasoned that because it’s relatively cheap, print-making evolved as a way to communicate with the masses.

“There’s always the hope that historically, people will find zines, maybe 50-60 years from now that talk about specific social justice topics from the time they were made,” she said.

A zine is a homemade, independently produced publication, usually about a personal or particular subject. Founded in 2001, the annual Zine Fest aims to “advance the do-it-yourself ethos,” by bringing together area writers and artists to participate in panels, watch workshops and share and hopefully sell their work.

There were panel workshops, screen-printing demonstrations and impromptu discussions and introductions.

Zine Fest co-organizer Neil Ballard fondly recalled his own days as an exhibitor and vendor as he stood near the entrance to the Metreon’s City View space, which also functioned as the event’s venue in 2022 for its in-person return after two virtual “cyberfest” editions of the gathering during the pandemic.

“This is just a really awesome way, once a year, where people can come together and share what their creative expression is,” Ballard said, noting that festival organizers would continue to host workshops with the San Francisco Public Library and partner with other zine festivals. “They can exist in this community we’re bringing, catch up and get the physical form of what all that creativity is throughout the year.”

This year’s festival guest of honor was nonbinary cartoonist Maia Kobabe, whose 2019 graphic memoir, Gender Queer, was named the most challenged book in the United States in 2021, according to the American Library Association and the free speech organization PEN.

At the festival, visitors wove slowly among the booths, stopping to browse and ask questions, slowly filling tote bags and backpacks with their purchases.

Oakland resident Anna Kingsley said she came to support her child, who was offering a zine on making dye out of pomegranates.

“It’s the best place to be,” she said. “The energy is amazing, the artistic skill is top-notch, everybody’s so nice and what’s that word? Welcoming?”

At one booth, Oakland artist Nick Lovett greeted people while abstract doodling.

“When I was younger, I thought zines were, like, a white thing,” Lovett said. “But zines can be for everybody, and they’re accessible, and that’s the whole point.”

Lovett, who creates under the name Black Girls Are God, said Sunday was her second zine festival this year. Much of her artwork and poetry deal with “sexual trauma, domestic abuse, being queer, mental illness. I call myself Black Girls Are God because I believe that within every Black girl, there is a God. I honor the God in me by creating art.”

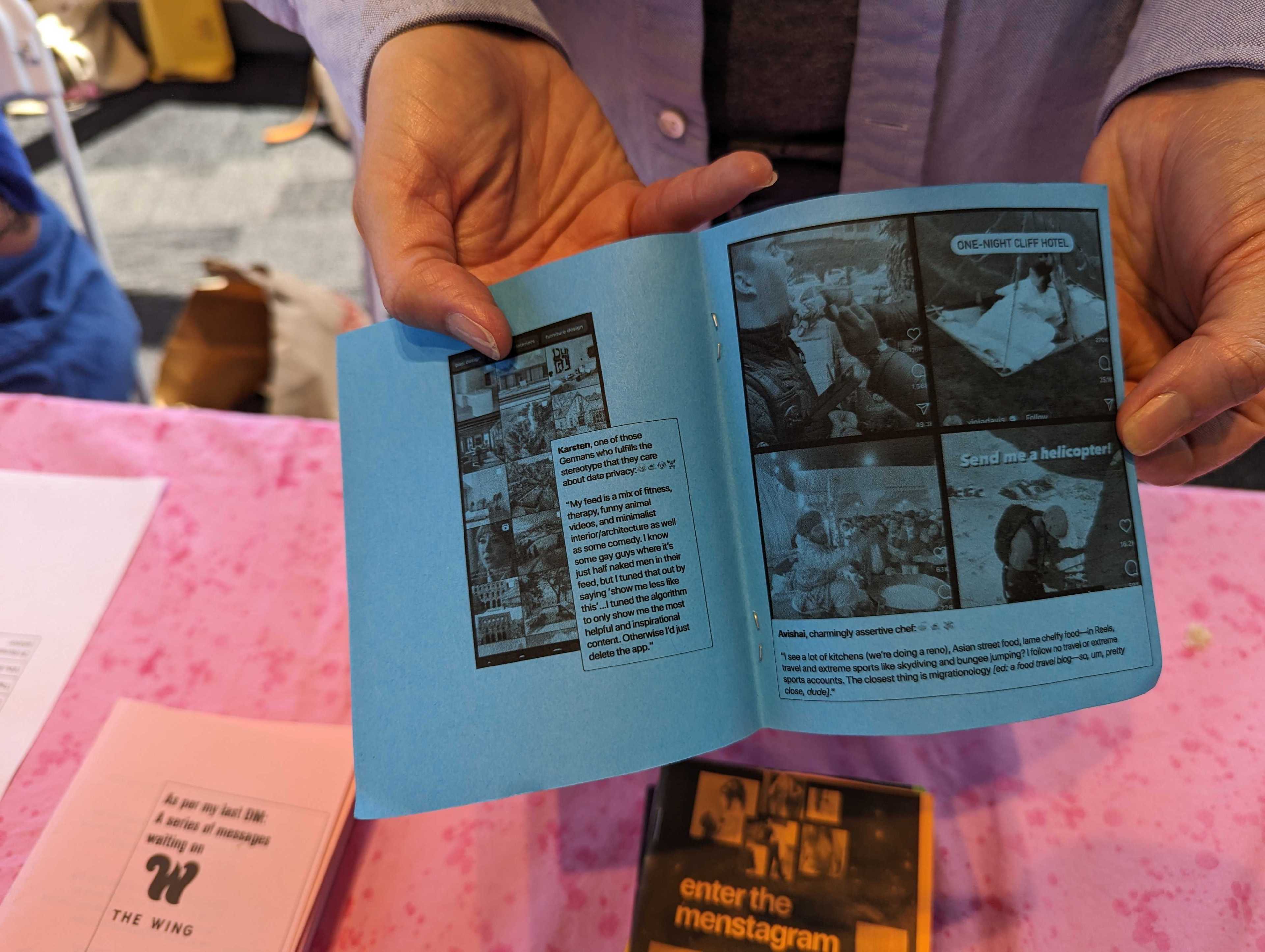

At another booth, Jane Justice Leibrock offered zines on beards, memories of visiting a “fat camp” and the nail-art scene at the Oakland Museum of California. She displayed a zine containing interviews and screenshots of men’s Instagram feeds.

Another titled “Who BARTed? Transcendental Transportation” was inspired by the Whole Earth Catalog and collected comics, speculative fiction and memoirs, said Leibrock.

“It’s just our way of looking at the system from all different angles,” she said.

Leibrock believes festivals like Sunday’s function as “a place where you can meet lots of really creative folks who are creating works mainly on paper just for the joy of it, to express whatever they uniquely love and want to share their love of with the world.”

Her table mate Molly Marriner put it more simply:

“Zines are a very good way of paying honor to a time honored way of disseminating your own thoughts.”