San Francisco mayoral candidate Daniel Lurie says he would not support opening safe-consumption sites—where people could use drugs under the supervision of people trained to reverse overdoses—if he’s elected to run the city.

Lurie, founder of the anti-poverty nonprofit Tipping Point and heir to the Levi Strauss fortune, suggested to The Standard that safe consumption sites would make the city a “shining beacon for drug tourism.”

The declaration sets Lurie apart from the incumbent Mayor London Breed. It also puts him in contrast to mayoral candidate Supervisor Ahsha Safaí, as well as many members of the Board of Supervisors who have voiced support for the sites in the past.

“Opening more places for people to do drugs … must be off the table,” Lurie said in an emailed statement. “We need to focus on shutting down open-air drug markets and getting everyone sheltered.”

Many drug policy experts have said safe-consumption sites are an effective way to reduce public drug use and overdoses. However, it’s unclear whether members of the general public share their support.

In a statement about her stance on safe-consumption sites, Breed’s campaign spokesperson said she supports a nonprofit using private funds to open such a facility.

“Opening one of these sites requires a strong community plan to ensure that the services provided don’t provide a negative impact on the surrounding community,” Breed said in a statement to The Standard. “We are working with the Department of Public Health and other agencies on what that would entail, if a site were to open.”

Lurie’s policy choice runs counter to the city Department of Public Health’s Overdose Prevention Plan, which calls for opening “wellness hubs” to provide overdose prevention, among other services.

The city operated a safe-consumption site called the Tenderloin Center for roughly 11 months last year and counted 333 overdose reversals under its purview. The site also provided 99,039 meals, 8,956 showers, 3,493 loads of laundry as well as 1,529 completed referrals to housing and shelter.

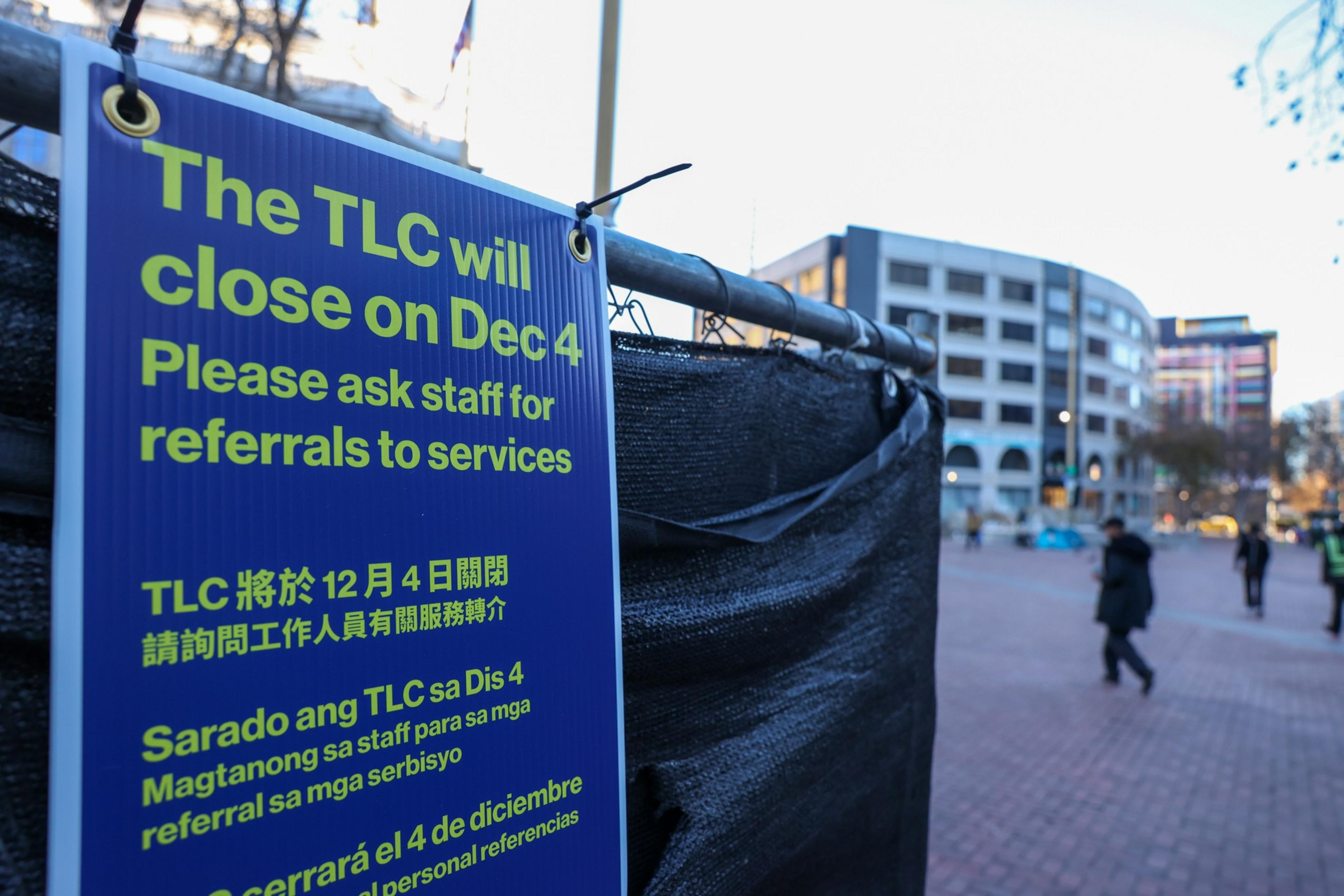

However, critics balked over the center’s apparent failure to connect many people to drug treatment, its impact on the neighborhood and its $22 million price tag. The site shuttered in December as the health department planned to open a string of smaller replacement facilities that have yet to materialize over legal concerns.

San Francisco is in the midst of a historic overdose crisis that’s seen the city break its own record for deaths in a month twice this year. In August, 84 people died of drug overdoses, according to preliminary data.

Lurie said his primary policy to address homelessness and overdoses would be to open enough homeless shelters to circumnavigate a federal ruling that’s restricted the city’s ability to enforce anti-camping laws.

He also said he would aim to fully staff the police department and expand drug and mental health treatment options.

“Once people are sheltered,” Lurie said, “it is easier to connect them to case managers, get those that are addicted or mentally ill into treatment, and identify who qualifies for permanent supportive housing.”