In recent decades, candidates for political office in San Francisco have developed a tradition of finding an “authentic” Chinese name to put on ballots. In the past, the process was somewhat freewheeling, in which non-Chinese candidates were more or less allowed to call themselves whatever they wanted. But the rules are tightening.

After an inquiry from Supervisor Connie Chan, the Department of Elections has decided to follow a 2019 state law saying self-submitted Chinese names may only be used if candidates can prove that they were born with them, as many Chinese immigrants or Chinese Americans were, or they have been using the names for at least two years.

If that’s not the case, candidates will then be given a transliteration-based name, which are often wordy and based on Mandarin phonetics.

As San Francisco is heading into an election season, the rule change may be considered a crackdown of sorts. Because of the city’s robust Chinese-speaking population, ballots are in both English and Chinese, which has led many non-Chinese candidates to adopt a Chinese name in an effort to appeal to monolingual Chinese voters.

For example, mayoral candidate Daniel Lurie, a first-time runner in politics, recently named himself 羅瑞德, and the name is widely publicized in the Chinese-speaking world. But if he can’t prove that he was born with the name or has been using it for two years, he will likely be assigned a name, 丹尼爾·露里.

Lurie’s chosen Chinese name means “auspicious” (瑞) and “virtue” (德), while the transliterated version name doesn’t have any meaning. It’s just an approximate pronunciation of his name in English: “DAN-knee-er LOO-lee.”

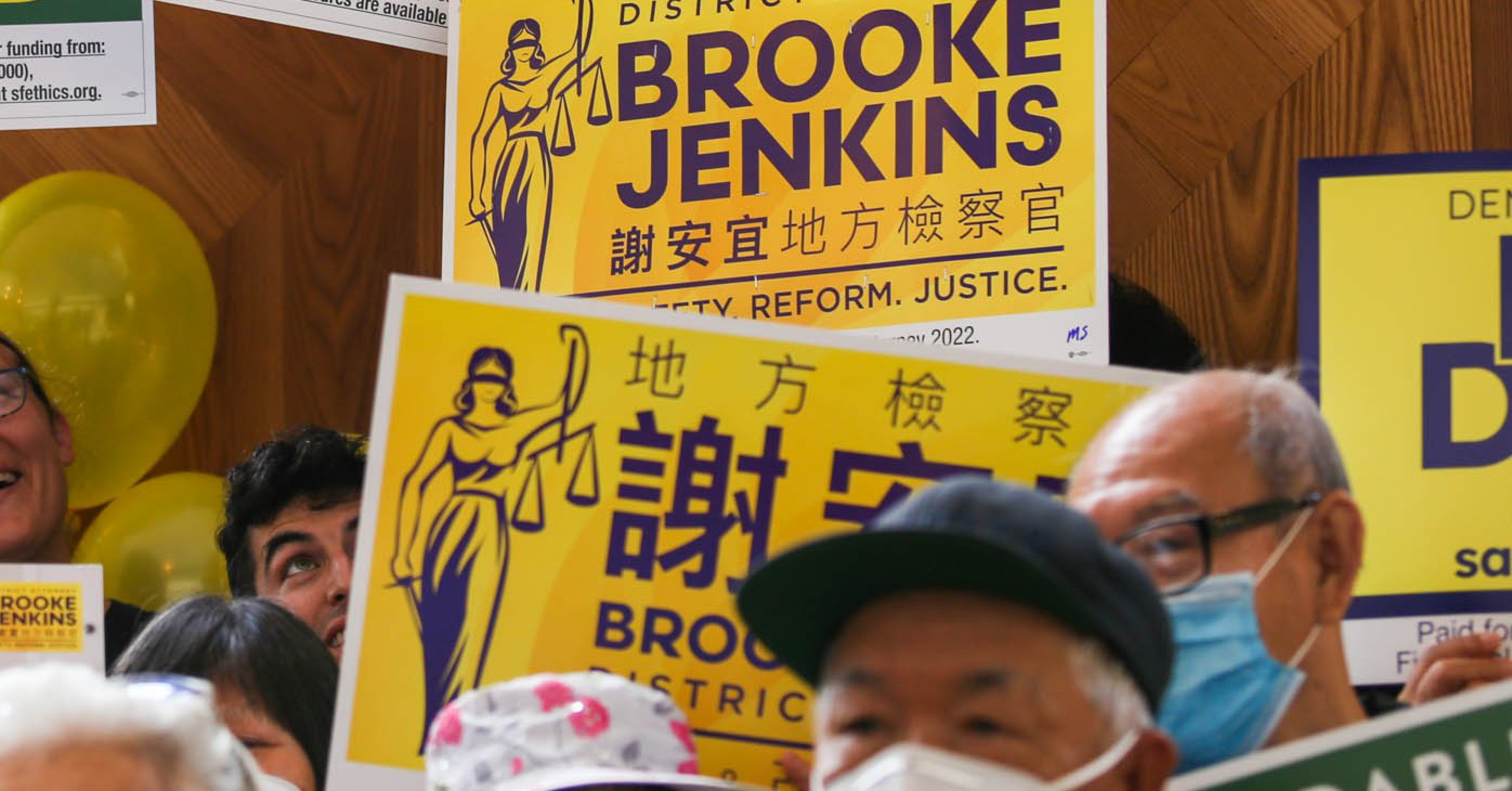

Among incumbents or well-established local politicos, the two-year threshold is easy to meet. For example, Brooke Jenkins named herself 謝安宜 (“safety, pleasant”) in July 2022 when Mayor London Breed appointed her to be the city’s district attorney. If Jenkins waits to file for reelection until next summer, she can prove she’s been using the name for two years.

Cultural Appropriation?

Chan, who is currently the only Chinese American on the Board of Supervisors, said candidates have clearly been taking advantage of the ability to use a Chinese name on the ballot.

“Cultural appropriation does not make someone Asian,” Chan told The Standard. “There is no alternative definition to whether someone is Asian or not. It should be based solely on a person’s ethnicity and heritage. That’s what this law is about.”

A specific incident between two local candidates triggered Chan’s inquiry. In a race for the local Democratic Party committee, Natalie Gee (who is Chinese American) accused (opens in new tab) a non-Chinese candidate, Emma Heiken, of using the same Chinese given name in her campaign.

Chan then urged the city’s Department of Elections to explain why San Francisco hasn’t implemented the state law that governs such matters. John Arntz, the director of the department, had previously insisted that the city has its own municipal law on Chinese names, so it doesn’t need to follow the state guidelines.

However, after consulting with the City Attorney’s Office, Arntz said in a letter to Chan (opens in new tab) last week that it will now follow the state law, citing potential abuses when using Chinese names.

“The Department can adopt a policy that sets a reasonable standard requiring candidates to demonstrate their use of a name or transliteration for the preceding two years when filing nomination papers,” Arntz said in the letter.

He couldn’t be reached for comment before publication.

Interestingly, American-born Chinese candidates may be unintended victims of the law, if they don’t have a birth certificate in Chinese that proves they were born with Chinese names.

Some candidates told The Standard that they have received requests from the Department of Elections asking for additional documentation on the Chinese names (opens in new tab), and were scrambling to seek old Chinese newspaper articles, Chinese school homework or Chinese family books to find the appropriate records.

David Chiu, the city attorney of San Francisco, voted in favor of the 2019 state law when he represented the city in the state Assembly. In a text message, he said that “to fully resolve the ambiguity between state and local law, the Department has requested that my office draft amendments to our local law so it more closely aligns with state law, which we will do.”

After the City Attorney’s Office adds the new language to the local law, the Board of Supervisors will need to pass it to make it official. It’s unclear how long the process will take.