He is a San Francisco Superior Court judge whose Japanese mother met her American husband in occupied Tokyo after World War II. His opponent is a corporate lawyer raised by a pair of attorneys, who grew up doing homework in his mother’s chambers at Santa Clara County Superior Court.

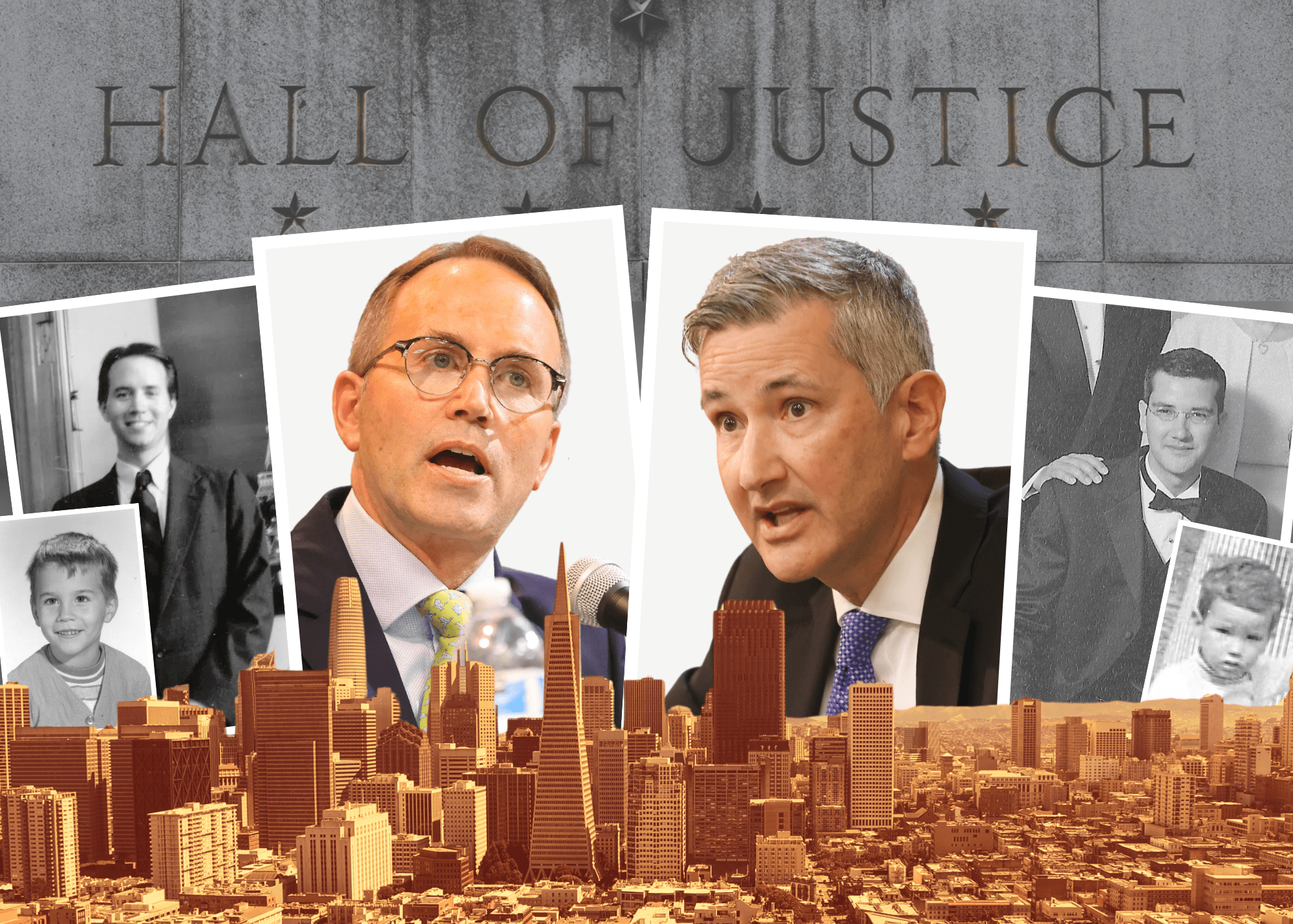

The biographies of Judge Michael Isaku Begert and his challenger in the March 5 election, Albert “Chip” Zecher, have played little role thus far in a heated campaign focused on crime and public safety.

Months before voting started, Mayor London Breed and District Attorney Brooke Jenkins made claims that judges are partly at fault for the city’s public safety issues because they release drug dealers pending trial. But the criticism, which is at the center of the contest, is countered by others, who say judges are only following the law—and are being used as scapegoats for some of the city’s most intractable problems.

Begert, who was appointed to the bench by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2010 and worked in private practice before becoming a judge, has significant support from local judges, the legal community and progressive politicians.

Zecher, who has worked for insurance companies and manufacturing firms, sits on the board of UC Law San Francisco and is backed by tough-on-crime groups like Stop Crime SF and some big tech money.

Begert’s supporters say Zecher’s campaign is a politically motivated effort to put fear into San Francisco judges so they are more harsh. Zecher’s backers deny that and point to what they say is Begert’s record of leniency that voters should consider when voting for the judgeship.

Begert’s and Zecher’s lives and careers have been less of a focus than public safety in the campaign. But their biographies may help voters understand how their personal stories could impact their decisions on the bench. Under judicial ethics rules, they are barred from discussing in detail how they would rule on future cases.

Judge Michael Begert: In the wake of World War II

Begert, 60, is a product of the wreckage of World War II.

Begert’s mother, Sono Nishimura, spent the war years in Europe as an au pair for a Japanese diplomat. By the war’s end, she didn’t know if her family had survived the U.S. bombardment of 1945 until her circuitous, monthslong return to Japan. Her father, who ran an art school in Tokyo, had been jailed because of his opposition to Imperial Japanese policies, but he and the rest of the family had survived the firebombing of the city.

Begert’s father, Carl Begert, came to Japan with the Air Force as part of the United States’ postwar occupation. For a time, he worked as a judge advocate general, or JAG, in military courts.

The pair met in Tokyo, and the romance stuck.

When Begert’s father was transferred back to the U.S. in 1949, his wife-to-be took a steamship to the Pacific Northwest. The pair married and raised five children in rural Washington state. Michael Begert was the youngest.

Begert describes his upbringing as happy; he spent summers picking berries or doing construction work for pocket money.

“The law is our attempt to approximate what we all agree is fair. At its best, it accomplishes that.”

Judge Michael Begert

After graduating from the University of Washington and the University of Chicago’s law school, he entered private practice.

“A lot of what you learn in law school is not to memorize the code, but to learn how to think like a lawyer,” Begert said of his time in Chicago. “The law is our attempt to approximate what we all agree is fair. At its best, it accomplishes that.”

He returned to the West Coast in 1989 and started his career with McCutchen, Doyle, Brown & Enersen in San Francisco.

“I wanted to be a litigator,” Begert said. “I wanted to be a trial lawyer.”

He worked on everything from commercial disputes and vehicle liability to chemical exposure and software piracy.

His pro bono work included helping a group of Black San Francisco firefighters in their battle against discrimination, which forced the department to change its hiring practices.

The case that stands out most was about the Japanese YWCA in Japantown. Before the Japanese internment during World War II, a group of Japanese immigrant women raised money for a community center. Laws barring them from owning property prompted them to make an agreement with the YWCA, which held the land in trust. Internment and its aftermath left the building in the hands of the YWCA.

Decades later, in the 1980s, the YWCA got into financial trouble and wanted to sell the building, but researchers discovered the original agreement. Begert filed a lawsuit, and in the end, the YWCA had to sell the building back to the original group of Japanese Americans for a fraction of the asking price.

“It really stopped the YWCA in its tracks,” said attorney Donald Tamaki. “It was really Michael Begert and his efforts to protect the building” that saved it.

Drug courts, mental health and treatment

After Schwarzenegger appointed him as a judge, Begert served in almost every role in the San Francisco Superior Court, from traffic to criminal and civil trials to family law and the juvenile courts.

“I have a lot of respect for the way he operates,” said Scott Sugarman, a defense attorney.

In 2019, Begert began his stint as the judge overseeing so-called “collaborative courts” for veterans, people with drug abuse issues and the mentally ill who had entered the criminal justice system.

In fall 2023, he was chosen to lead a new court—the Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment Court, or CARE Court—created by Gov. Gavin Newsom. CARE Courts aim to help people with mental disorders before they have criminal cases.

“I work every day with my primary focus being improving the safety and vitality of the community,” Begert said. “I try to help people access the help that they need.”

Former prosecutor Judith Garvey, who worked in the collaborative courts before Begert, said that Begert is talented in both getting people to go into treatment and holding them accountable when they fail.

“He knows how to draw the person into treatment. It isn’t easy. It is a real talent,” she said. “The clients recognize, respect and respond to it. He remanded and kept people in custody when appropriate for public safety.”

The 5,000-plus member San Francisco Bar Association, meanwhile, gave Begert a “well qualified” review, nearly its highest rating. Zecher declined to participate in the review.

‘Revolving door’ judge?

Begert’s track record over the past four years has come under scrutiny as the city’s debate over public safety has focused on open-air drug dealing.

Detractors have claimed Begert is too lenient and has a penchant to release repeat offenders. Critics like former Judge Quentin Kopp call Begert one of the city’s “revolving door” jurists. The political nonprofit group Stop Crime Action alleges that Begert has released repeat offenders, who then committed crimes again. The group’s “judge report card,” boycotted by most San Francisco judges, gave Begert a failing grade.

In September, an anonymous poster falsely claiming Begert released a repeat fentanyl dealer appeared on city streets.

It claimed that Nicol Palma was arrested in 2021 and 2022 on drug charges and was ordered released by Begert and another judge. But Palma had already been released when her case came before Begert. Her case was then dismissed due to allegations that the arresting officers’ search of Palma was illegal.

“They are just flat wrong whether I am the guy releasing people.”

Judge Michael Begert

Begert denies the claims made against him and says that the people making them don’t seem to understand the law.

“I never released that young woman in the poster. She was already out of custody when she came to my court. More importantly, both of her cases were dismissed at the request of the DA for ‘lack of evidence,’” Begert said.

“They are just flat wrong whether I am the guy releasing people,” he said about his critics.

Unlike CARE Court cases, the collaborative court cases Begert handles are sent to his court after the district attorney and the public defender agree that each defendant is eligible to work in the collaborative courts, which require them to participate in treatment, community service and other programs.

Deputy Public Defender Alexandra Pray, who handles most defense cases in the collaborative courts overseen by Begert, said the law is very specific about who is eligible and how they must behave while they are taking part.

Decisions about detention are usually decided in normal criminal courts, before cases are referred to Begert.

Some attorneys and judges who work in the San Francisco courts have defended Begert, saying his critics are off base.

“The irony of this challenge to Judge Begert is he hasn’t been in a court that makes the decision” he is being attacked for, Judge Jeff Ross said of allegations about Begert releasing defendants.

“I don’t understand exactly why he has been selected to be challenged by Stop Crime SF and other organizations,” Ross added. “But they got the wrong guy.”

Two cases have been the focus of Stop Crime SF’s critique; in both, the group alleges Begert let defendants who were a danger to the public out of custody.

Anna Boddy, a transgender woman with mental health and drug issues—she is on a sex offender list out of state—was picked up on a burglary case and admitted into the drug and mental health courts Begert oversees.

Deputy Public Defender Eric Quandt, who represented Boddy, said that his client suffers from substance abuse and mental health issues, which is why she was referred to Begert’s court.

“No one has been injured,” Quandt said. “These are property-related crimes.”

But after Boddy was sent to his court, she picked up a new case, so was sent back to normal criminal court. When she was recently referred to his court again, Begert denied the request, Quandt said.

The other case Begert has come under attack involves Sebastian Mendez, a mentally ill man who attacked police officers in June 2023. Mendez was released by another judge and ordered to wear an ankle monitor, put into a drug treatment program and referred to Begert’s court for a treatment plan. Before that process was done, Mendez violated the ankle monitor agreement and was returned to jail, Begert said.

Begert played no part in his detention or release, he said.

Many attorneys and judges say the attacks on Begert have little to do with his actions, but instead are an attempt to strike fear into the bench.

“Aside from the merits of the candidates,” defense attorney Randall Knox said, “I think that this appears to be another attempt to scapegoat people for something that is not their responsibility.”

Albert ‘Chip’ Zecher: From a family of lawyers

Zecher, 59, lives in San Francisco but grew up with his two sisters, one of whom is now a judge, in a South Bay household of lawyers.

“We just always grew up around law. I never thought of anything different,” he said about his future career.

In fact, his parents met in a courtroom.

His mother, Marilyn Pestarino Zecher, came from an Italian immigrant family and, at one point, worked for her family’s clothing store in downtown San Jose before she became a lawyer and a judge.

“We just always grew up around law. I never thought of anything different.”

Albert “Chip” Zecher

His father, Albert “Mike” Zecher, from San Francisco, ran a private practice, and for some years, his parents worked side by side.

“Very active intellectually” is how retired Santa Clara County Judge Philip Pennypacker, who knew Zecher’s parents, described the Saratoga household.

Politics were a common theme at their dinner table, from supreme court cases to local trials in the county court, Pennypacker said.

Zecher’s mother eventually became the county’s first woman presiding judge after Gov. Ronald Reagan appointed her in 1975. Being the best candidate was more important than being the first woman, so she “never played that hand,” Pennypacker said.

Zecher spent hours after school in her courtroom, listening to cases as he did his homework, he said.

After attending Santa Clara University where he studied art history, he moved to San Francisco and got his juris doctor at the University of San Francisco Law School.

For two years in the early ’90s, after law school, he worked as a researcher for San Francisco Superior Court before moving into private practice.

From 1995 to 2002, he worked for the Chubb group of insurance companies.

“I loved the trial work. It’s a mystery. You unravel a mystery,” Zecher said about applying the law to the facts of a case.

In 2003, he had a brief stint in politics when then-Mayor Gavin Newsom put Zecher on his transition team.

In the late 2000s, Zecher began working in Silicon Valley for a high-tech manufacturer of satellite amplifiers.

During that period, he mostly wrote contracts for civil and military work, which he says was about thinking through every potentially negative outcome.

“You understand how to structure a deal when things fall apart,” he said. “I learned business there.”

In 2013, he started working for Intevac Inc., which makes digital night vision devices and glass for cameras and cellular phones.

Outside of work, Zecher has played an active role on a number of arts boards and a private school in the South Bay.

He also taught night school at Sacramento’s Lincoln Law School. The former dean of the school, Joseph Heya Moless, said Zecher was a dedicated teacher to students who were mostly from immigrant and underserved backgrounds.

“He understood that integrating this segment of our society into the legal system was important for the success not only for themselves but for their community,” Moless said.

Zecher’s face can also be found in the pages of San Francisco publications chronicling society events, such as at the opera and symphony opening galas.

A school’s violent namesake

By 2019, Newsom had become governor, and he appointed Zecher to the board of what was then called UC Hastings, now known as UC Law San Francisco.

Zecher played a role in the school’s renaming and its effort to increase public safety near its campus near City Hall in the Tenderloin neighborhood.

UC Law San Francisco Dean and Chancellor David Faigman said that Zecher has been an “active and positive” member of the school’s board of directors.

When the school was studying the genocidal history of its namesake, Serranus Hastings, and considering how to go about rectifying the school’s link to Hastings’ role in exterminating thousands of California native Americans, Zecher played an important part, Faigman said.

Zecher co-authored a memo the board used to make its decision to change the school’s name, Faigman said.

“That put him right in the center of it all,” he said.

Zecher also helped the school deal with combating crime in the area.

When Zecher joined the UC Law board, “it was really an eye-opener of what’s going on in the city,” he said.

In the violent early ’90s, when Zecher worked for the superior court, the neighborhood was “colorful, but I didn’t fear for my safety,” he said.

In 2020, crime got so bad the school sued San Francisco, claiming the city was not equitably enforcing the law in the neighborhood, Faigman said.

“Chip has been very supportive of the college’s efforts to make sure that our voices were being heard,” Faigman said of the legal battle with San Francisco, which the school won.

Zecher said crime on the streets in the Tenderloin, and the DA’s claims about judges being to blame for it sparked his decision to run for judge.

He said in the spring or summer of 2023, he started hearing statements by Jenkins, the DA, that she was “having issues with the judges.”

Zecher, who has never been the victim of violent crime, said he is fearful in a city he has lived in for much of his adult life. He lives in the Sunset District.

“I don’t walk around San Francisco after dark without someone with me,” he said. However, he added, he would “go out at night in the Sunset.”