Macy’s decision to shutter its iconic San Francisco location in Union Square represents the shocking end of an era for a once-mighty retailer laid low.

“The latest Macy’s news is a classic example of a legacy brand on a slow but steady decline towards irrelevance,” said Michael Berne, president of retail consultancy MJB Consulting, adding he found the Union Square decision unwise given the importance of large brands maintaining flagship stores in major markets.

Berne said while there could be many possible factors, such as consumer tastes and habits evolving, it is hard not to consider Macy’s efforts to fend off a hostile takeover (opens in new tab) when thinking about why the company would shutter such a historic location at this time.

The city will get at least a brief reprieve from the gaping 700,000-square-foot vacancy that Macy’s will leave behind. The retailer is still analyzing its ability to sell the property and the earliest the store would close is 2025.

“Macy’s has always meant a lot to the people of this city. It’s where families came to shop for the holidays,” Mayor London Breed said in a statement. “It’s where many people from my community got their first jobs, or even held jobs for decades. It’s hard to think of Macy’s not being part of our city anymore.”

Union Square icon

For decades, the store was a steadfast presence downtown, acting as the backdrop to innumerable tourist photos and functioning as a holiday destination for generations of Bay Area residents. Now, just as the former Westfield mall a few blocks away sits as a mere shadow of its former self, the impending departure of a Union Square stalwart is a blow for a city in sore need of positive news.

Macy’s came to San Francisco in 1945 through the acquisition of local department store company O’Connor, Moffatt Co., taking over and rebranding the building at 101 Stockton St. as part of a national growth plan.

The company went on a gradual expansion and build-out in subsequent years, incorporating 170 O’Farrell St. to its storefront in a 1948 expansion. In the years following, a bankruptcy filing, an attempted takeover and various mergers made the San Francisco flagship the centerpiece of the company’s Macy’s West division.

In 1984, Macy’s opened a separate men’s store in San Francisco at 120 Stockton St.—at the time one of the largest men’s department stores in the world—across from its central Union Square location.

At its peak in the mid-1990s, Macy’s dominated San Francisco’s premier shopping area, spanning some 1.1 million square feet of retail space across its flagship at 170 O’Farrell St., the I. Magnin Building at 50 Grant Ave. and the Macy’s Men’s store.

Then came the rise of e-commerce and the shift away from big-box retailers. Store closure announcements started becoming a regular pattern for Macy’s, including 40 stores in 2015, 100 stores in 2017 and 150 stores this week, including San Francisco’s Union Square location.

San Francisco sell-off

Amid slowing sales and falling stock prices, Macy’s cannibalized a slice of its San Francisco real estate holdings for cash after failing to convert portions of its stores into different uses.

In 2016, the company sold its 250,000-square-foot men’s store at 120 Stockton St. to Morgan Stanley and Blatteis & Schnur for around $275 million.

The retailer shifted its men’s apparel into its flagship location, and 120 Stockton was subject to a yearslong mixed-use redevelopment. New tenants of the property include on-demand meeting and event space company Convene and buzzy Japanese-Peruvian rooftop restaurant Chotto Matte.

Then in 2019, Macy’s sold off the former I. Magnin building at 233 Geary St. to Palo Alto developer Sand Hill Property Co. for $250 million. Before the pandemic, the new owners pitched a project that would split up the building into retail space, offices and residential segments, but the current San Francisco real estate freeze means plans were largely put on pause.

The building is currently the home of Union Square’s Louis Vuitton store, perhaps best known as the site of the viral smash-and-grab robberies that took place in November 2021.

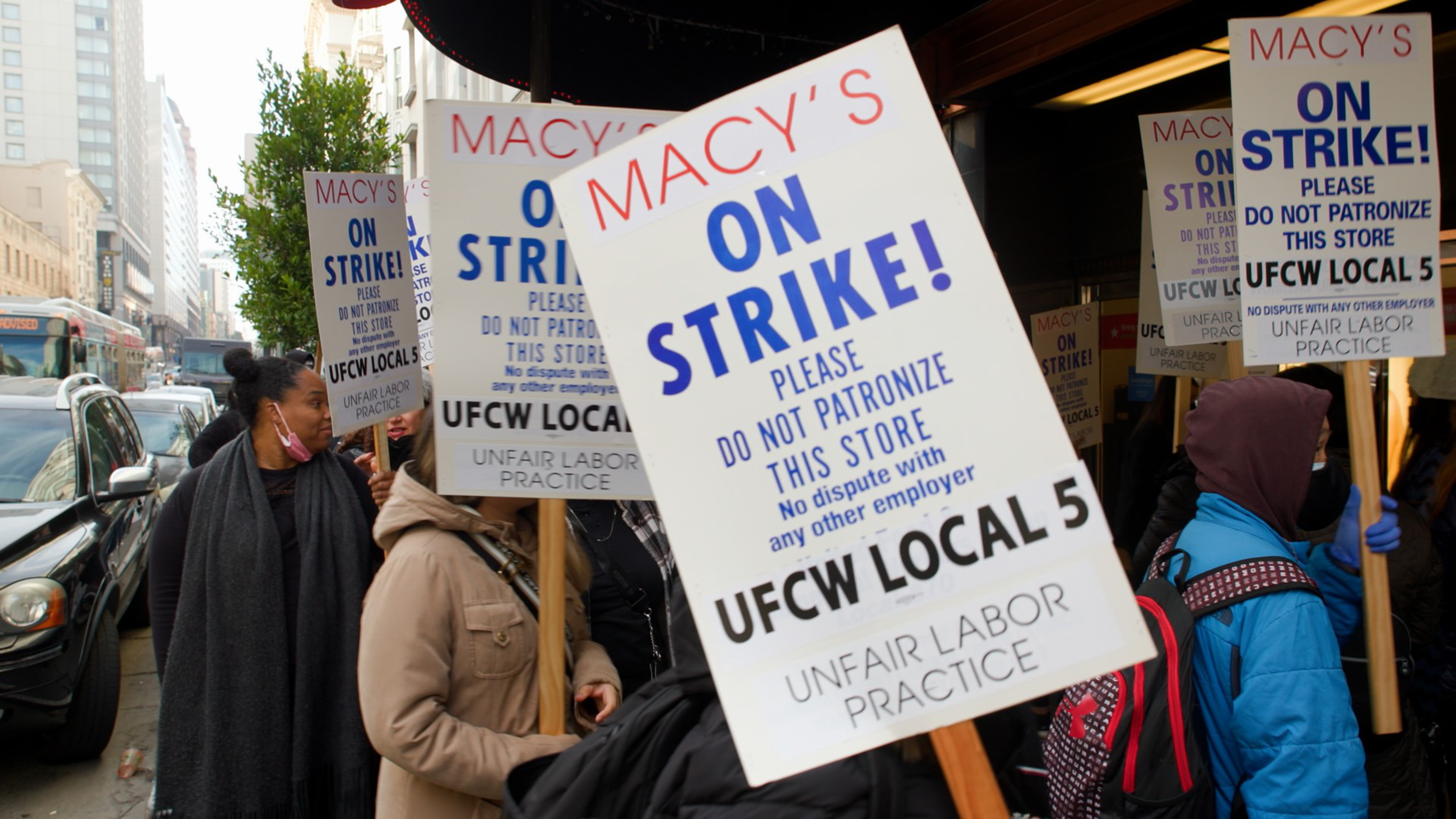

In a signal of the declining value of San Francisco real estate and Macy’s declining prospects, the company has attempted to significantly cut the assessed value of its flagship building in recent years to save on its property tax bill. As if flagging sales weren’t enough, during the peak holiday shopping season in 2022, over 400 Macy’s workers also walked out on their jobs, striking against staffing and benefit cuts.

The store closure announcement marks a logical endpoint for a company that has gradually shed its San Francisco presence.

“While retailers close stores for various reasons, one of the reasons that is often central to the decision is demand for their product,” said Alex Sagues, a San Francisco retail broker at real estate firm CBRE.

Macy’s more recent woes have been accelerated by a series of hostile takeover attempts from private equity firms and activist investors. Last week, private equity firm Arkhouse Management nominated nine new members (opens in new tab) to Macy’s 14-member board of directors after its unsolicited $5.3 billion bid to purchase the company was denied.

Earlier this month, after culling 13% of its corporate staff and shutting down a handful of other stores, the New York-based retailer elevated Tony Spring to CEO after he spent nearly 35 years at Macy’s Bloomingdale’s division.

His strategy for turning around the flailing company? Reducing the number of Macy’s locations to 350 stores over the next three years and adding around 45 Bloomingdale’s and Bluemercury locations in their stead.