The City College of San Francisco serves all comers, from low-income students to adults returning to school, whether for a first degree, a career change, or just a love of learning. But for a decade now, the school, free for San Francisco residents, has been buffeted by uncertainty.

In 2012, accreditors threatened to shut down the college (opens in new tab) over poor management. Though City College resolved that issue (opens in new tab), it’s now on the brink of losing millions of dollars (opens in new tab) of state funding if it can’t increase enrollment quickly (opens in new tab). Once boasting a population of over 100,000 students, the school had shy of 38,000 enrolled during the 2022-2023 school year.

Administrators are in a race to ensure City College remains a viable part of the city’s civic fabric. But at a recent board meeting Anita Martinez, vice president of the City College of San Francisco Board of Trustees, sat behind the dais and mused about another core issue of concern: parking.

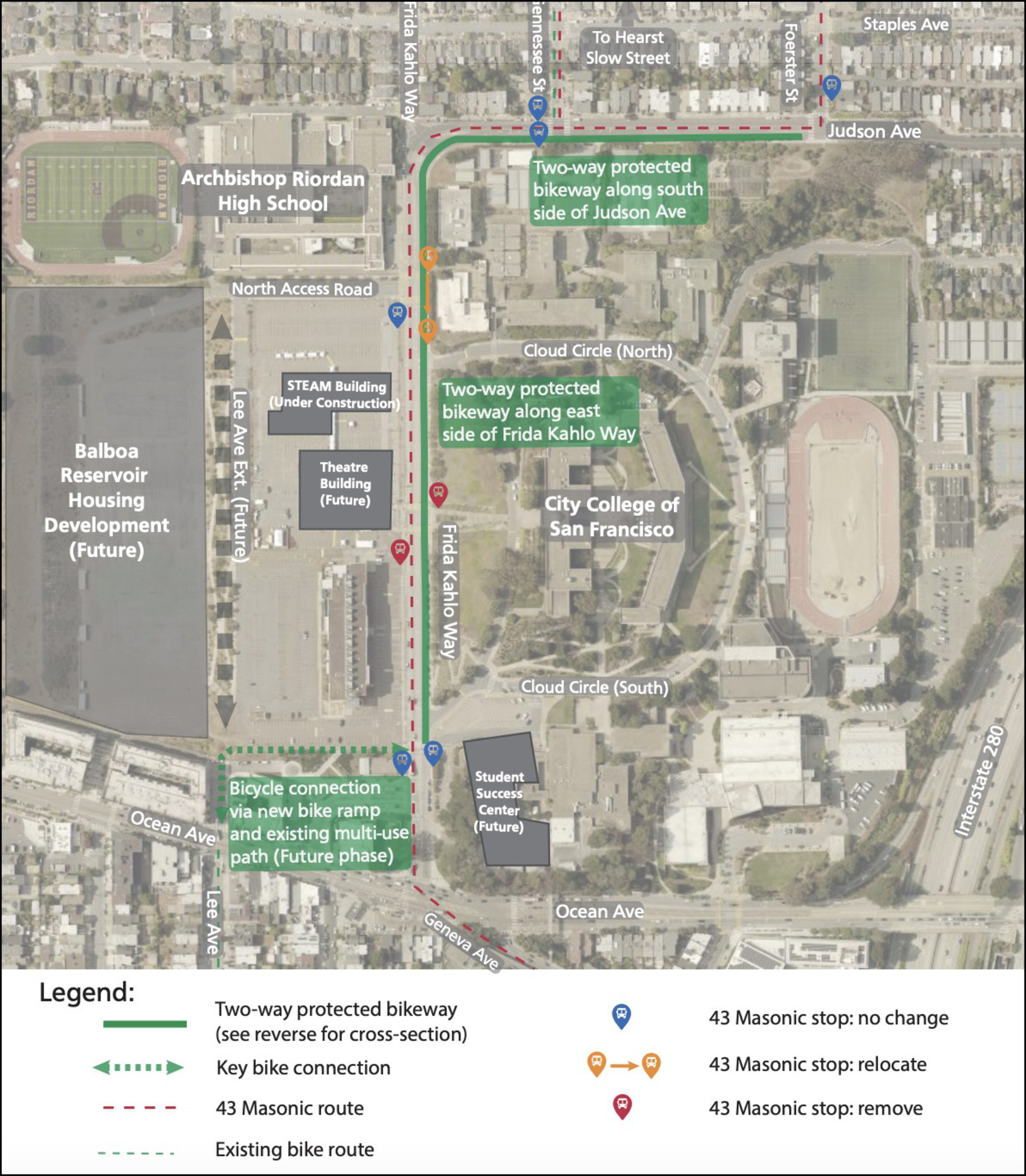

On her mind was a San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency plan to build a half-mile-long protected bike lane along the college’s main drag. SFMTA hoped it would be an innocuous, speedy project, eliminating just 29 public parking spaces and nine motorcycle spots, according to agency spokesperson Michael Roccaforte. That’s less than 1% of City College’s total parking supply. But in San Francisco, messing with parking is grounds for a brawl.

Martinez and other leaders among the students, administrators and faculty who populate the leafy Ocean Avenue campus say deleting those spaces could be the latest gale force to send students into exodus. “Students will go,” she said, “where it’s easy to park.”

SFMTA’s critics at the college say the loss of parking isn’t just an inconvenience; it’s nearly an existential threat to a school that can ill-afford one. It’s an overreach by an agency abusing its newfound power to quickly push transportation projects in communities that don’t want them. And it’s coming on the cusp of other construction projects that will broadly remake the look and feel of the campus forever.

But the project’s critics haven’t been the only ones sounding off about the proposal. Supervisor Myrna Melgar, the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition, the Slow Hearst neighborhood group and a slew of others have all voiced their full-throated support for the new bike lane, saying it’s a crucial link in the city’s plan to reduce its reliance on cars.

After a year of ferocious fighting, opposition, resolutions and delays, the SFMTA Board of Directors is scheduled to determine the fate of the bike lane plan next Tuesday.

Bikeways and Bulldozers

In 2014, San Francisco set out to eliminate traffic fatalities, adopting Vision Zero, a vogueish framework now popular in urban cores around the country. A major plank of Vision Zero involves reengineering streets to keep pedestrians, cyclists and transit riders safer. Hence, the SFMTA has built 52 miles of protected bikeways (opens in new tab) over the last decade. But because such redesigns often reduce space for cars and parking, a block-by-block conflict has beset nearly every one of those projects.

Before many of those bike lanes were built, and in a few cases well after, pitched battles have played out in community and SFMTA meetings. Neighbors and local businesses square off against the city and one another, both sides armed with petitions and hours of passionate public comment in support of the change, or lack of it, they want to see on their streets.

To cut back on some of the city’s notorious red tape and NIMBYism, San Francisco in 2019 launched its Quick-Build Program (opens in new tab), meant to allow the SFMTA to implement street safety proposals within a matter of weeks or months, rather than years.

So when, in the spring of 2023, the SFMTA proposed installing protected bike lanes (opens in new tab) running alongside the City College of San Francisco’s Ocean Campus, agency brass hoped they had the wind at their backs. They were wrong.

The proposed bike lanes would travel through campus on Frida Kahlo Way, from Ocean Avenue to Judson Avenue, where they would turn onto Judson and taper off after two blocks. The new bike lane on the east side of the street would be physically divided from the road by safety posts, a change from the existing painted bike lanes already on the streets, which don’t have a barrier between cyclists and cars. Agency officials thought the project, which also included modifying bus stops and other street safety changes, would escape the fate of so many before it and remain “relatively uncontroversial,” according to an SFMTA report (opens in new tab).

But by the fall, the project faced major opposition from City College, pressuring the SFMTA to slow down its work. The criticism focused on the loss of parking spots, which totaled 46 in the first proposal. In early 2024, the agency revised its designs, adding back some of the previously axed parking spots and leaving a single two-way bike lane on the east side of Frida Kahlo Way rather than having bike lanes on both sides of the street.

The appeasement failed. First, the Ocean Campus student council came out against the revised proposal. Then, the City College Board of Trustees passed a motion opposing the plan unless it was amended again to further address community concerns. The governing bodies of City College wanted to save its street parking—especially as the campus prepares for the arrival of bulldozers that have nothing to do with building bike lanes.

Twenty-nine spots

The future availability of parking spots on Ocean Campus is very much in question—but for reasons that have little to do with a bike lane. Though the bike lane may eliminate just 29 spots, SFMTA says that the overall site plans have put about 1,800 spots, roughly 60% of the total supply, on the chopping block.

In December 2022, San Francisco transferred ownership of one of the main City College parking lots to a developer group, which is slated to begin building about 1,100 housing units on the Balboa Reservoir site next year. Meanwhile, the college is in the midst of constructing an academic building in the middle of its other main parking lot and plans to erect a theater building in that same lot.

Administrators are looking into solutions for the car crunch. City College is preparing to put out a request for proposals to build a parking structure on campus, Facilities Manager Alberto Vasquez said during a December public meeting. Neither Vasquez nor the City College communications team replied to requests for comment on this story.

Students are already feeling the pinch, according to Travis Ezell. The business administration student serves as a senator on the Associated Students Council of Ocean Campus, regularly drives to campus and opposes the bike lane proposal.

Even with a parking pass, which costs $50 for the semester or $30 for students who receive financial aid, Ezell said he still has to hustle to class early on weekday mornings to make sure he can find a spot.

“Parking is very difficult to find around the area; this is going to make it more difficult,” Ezell said about the quick-build.

Martinez, the board vice president, who previously served as City College’s dean of students, said she’s heard complaints for years that even after buying a City College parking pass, students have had a hard time finding spots in the institution’s parking lots.

“That’s not a parking pass; it’s a hunting license,” she said at the March board meeting.

To Ezell, the SFMTA proposal is trying to fix a problem that doesn’t exist, because there is already an unprotected bike lane along Frida Kahlo Way and there haven’t been any bicyclist crashes on the route in the past five years.

Climate change, not collisions

If the construction of a bike lane leaves less space for students who drive to their classes, that’s entirely by design.

“We are not exclusively being reactionary to collisions on the street,” SFMTA Project Manager Casey Hildreth said during a July 2023 City College facilities meeting. The city is not solving for bike crashes, in other words. Rather, the bike lane is a link in a long chain of projects aimed at reducing San Francisco’s contribution to climate change. It’s a nudge to encourage city drivers to ditch their cars and instead hop on a bike, get off at a shiny new bus stop or take the ride on BART.

“We have all these people coming to the city. They cannot all be in a car. That is not the future of San Francisco,” Hildreth said. There’s only one way this all adds up: Less space for cars is actually the point.

Yet for many people in the City College community, driving a car is the only option. Photography student Jess Nguyen said that some of her classmates navigate long commutes from other counties that aren’t easily reached by public transportation or on bike, while others struggle with homelessness and live in their vehicles. She drives to campus from her home in the Mission because she would feel unsafe walking to and from the train with pricey camera equipment after her night class lets out.

“People who are able to write off certain things as just a parking spot … come from privileges where someone doesn’t realize that it could be their lifeline,” Nguyen said.

About a third of City College students drive alone to campus, with another 10% carpooling, according to the institution’s most recent transportation plan (opens in new tab), which was published in 2019. Nearly half of students take transit to class, with about 5% either walking or biking. Meanwhile, over two-thirds of the faculty drive to campus.

San Francisco city leaders have come together behind street safety in recent months, galvanized by the horrific crash that killed a family of four in West Portal and the failure of the decadelong Vision Zero initiative to stem traffic deaths. But the City College bike lane proposal illustrates that even as the tone at the top has come out strongly in support of safe street infrastructure, the nitty-gritty of implementing those changes remains mired in micro-neighborhood battles.

Transportation advocates like Sara Barz, a Sunnyside resident who lives near the proposed bike lane, say the conflict illustrates why San Francisco has thus far failed in its stated vision (opens in new tab) of a completely connected citywide “active transportation network,” that would stitch together a series of bike lanes, slow streets and car-free streets.

“It’s a problem that, frankly, a relatively small project like this takes so long to get through the community outreach process today,” said Barz, who serves on the San Francisco County Transportation Authority Community Advisory Committee. “We need to stop fixating on the people who just don’t want anything to change. Those things aren’t rooted in constructive criticism. They’re rooted in a place of wanting everything to stop.”

Ready or not

Many City College community members opposing the bike lane have pleaded for the SFMTA to wait until the planned residential and academic construction projects finish before thinking about changing the streetscape. But that upcoming change is exactly why it’s the right time to change the transportation systems in the neighborhood, according to SFMTA Director Jeffrey Tumlin.

“In order to accommodate the growth in this part of the city, we have no choice but to make sure that the most geometrically efficient modes of transportation work,” Tumlin told the City College Board of Trustees during a March meeting. Taking Muni or biking takes up 10% as much space as driving, he said.

Bike advocates see the Frida Kahlo Way proposal as a key step toward improving bicycle infrastructure in a part of the city that’s difficult to navigate due to hilly terrain, bustling streets and few bike lanes.

“Currently, it’s quite challenging and scary to bike around there,” said San Francisco Bicycle Coalition Westside Community Organizer Rachel Clyde.

If implemented, the Frida Kahlo Way protected bike lane would shuttle cyclists north to Hearst Avenue, a Slow Street they could take east toward downtown, according to Clyde. South of Frida Kahlo Way is Holloway Avenue, a key cycling route west to San Francisco State University.

While City College has made its opposition to the plan clear, the vast majority of individual comments SFMTA has heard on the proposal have been positive, according to SFMTA Board of Directors Chair Amanda Eaken. She said she plans to support moving the project forward because it will improve the city’s bicycle network, moving infrastructure toward the SFMTA’s goal of getting 80% of trips to be walking, biking or transit.

“Our street space is overwhelmingly allocated to the storage and movement of vehicles,” Eaken said. “We’re really just talking about making a very small additional amount of street space available to support biking and walking and transit.”

Eaken’s position ahead of the pivotal May 7 vote before the board may be disheartening to the City College community members who have led the opposition against the quick-build. Many of them, including music instructor Harry Bernstein, still feel that SFMTA hasn’t done enough to incorporate community feedback, even after revising the original proposal.

“They don’t do very well in hearing community input,” Bernstein said of the agency. Except in this case, SFMTA officials have heard it all. They just want to build the bike lane anyway.

After years of SFMTA’s Safe Streets projects being gummed up by their opponents, Mayor London Breed came out against the tactic during a March press conference. She laid out her vision for overhauling city streets to improve safety—and it didn’t sound like she was interested in arguments over parking spots.

“One of the things that I’ve been consistently talking about is getting rid of the bureaucracy to move forward,” Breed said. “Yes, we want community engagement. But sometimes, it’s just a little too much.”