As the sunset cast red hues over West Portal skies, residents of San Francisco’s west side funneled into the Scottish Rite Masonic Center’s banquet hall to condemn the city’s rezoning proposal, which aims to increase height limits in residential neighborhoods across San Francisco.

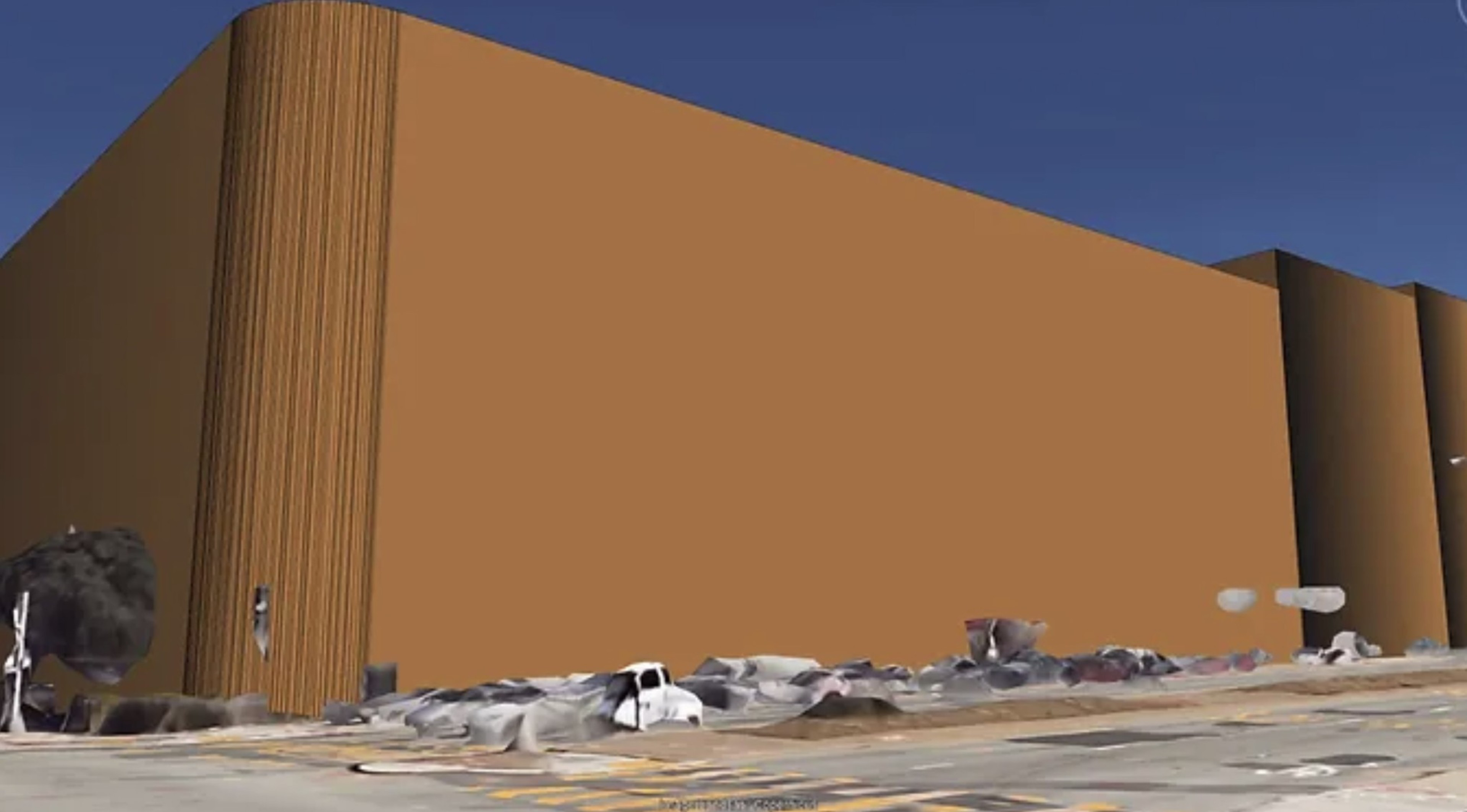

Renderings of what looked like spaceships parked in San Francisco’s sleepy west side neighborhoods were met with gasps from dozens of attendees, most of whom said they were homeowners, at the Wednesday meeting held by Neighborhoods United San Francisco, a collection of over 50 neighborhood groups mobilizing against upzoning proposals brought forth by the Planning Department.

The matter of rezoning has provoked the wrath of residents across the city, notably in west side neighborhoods with a preponderance of single-family homes, but also in wealthier areas on the north side. Despite making up only 2.7% of the city’s population, for example, the Pacific Heights neighborhood made up 28% of feedback citywide on the first rezoning proposal draft—the highest rate of participation across the city’s neighborhoods.

Leading the meeting was Lori Brooke, an anti-development firebrand who wears many hats in San Francisco civic life. She is the co-founder of RescueSF, a group attempting to lobby for homelessness policy changes, and longtime president of the Cow Hollow Association.

In a nearly hour-long presentation, Brooke painted the city’s rezoning plans as unnecessary, punitive and ineffective. The rezoning proposal must be approved by the Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors by January 2026 to help make way for 82,000 new housing units by 2032.

Hoping to rally supporters to use as a battering ram for a Thursday Planning Commission meeting on the proposal, Brooke described a harrowing future San Francisco devoid of viewscapes and affordable housing.

“Who’s going to want to live in one of these?” she asked the crowd, pointing to a rendering of an eight-story building. “It’s not just personal views, it’s public vistas, it’s the things that make San Francisco iconic and special. If you want to live in a city that has tall towers, there are plenty of places in this country to go.”

Neighborhood United’s detractors have criticized Brooke for employing scare tactics, misinformation and red herrings in her quest to block rezoning.

Brooke flipped from slide to slide of renderings showing what mid-rise buildings could look like in residential neighborhoods, bracketing entire neighborhoods and cutting views and hope for sunlight. Anne Yalon, a spokesperson for the Planning Department, called the renderings bogus and an attempt to steer the narrative against housing development.

“These crude boxes they’ve drawn on the website are completely out of scale,” Yalon said. “It’s not what an eight-story or 14-story building looks like. They’re using these fear-mongering tactics to get people on board, but if we don’t do this, we’re in big trouble,” Yalon added, referring to the city’s rezoning plan.

Mike Antonini, a Republican who served as planning commissioner from 2002 until 2016, kicked off the meeting with warnings about waterfront towers that could be erected from the Richmond District down to Lakeshore. He foretold plummeting property values, likening the rezoning plan to Soviet tenements before quoting Ronald Reagan: “The loss of freedom is only a generation away,” he said. Two more former planning commissioners—Dennis Antenore, who served in the 1990s, and Dennis Richards, who resigned in 2020 amid a lawsuit against the Department of Building Inspection—have also thrown their support behind Brooke’s group.

Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who’s running for mayor, echoed fears about the ill-effects of development in San Francisco, criticizing developers eager to stake claim to properties citywide and asserting that land development has historically been under the purview of local government.

“We should not forget the dark days of San Francisco’s experience with redevelopment in the 1950s and 1960s, now widely seen as a colossal planning mistake with deep racist undertones that led to the displacement of thousands of predominantly low-income people of color in San Francisco’s Fillmore District and Japantown,” Peskin said.

If the city fails to meet its state housing mandate by 2032, it could result in a loss of potentially hundreds of millions of dollars in state funds that go to transportation, parks and affordable housing and lead to “builder’s remedy” projects that bypass local zoning rules and could bring much taller projects.

To make it possible to accommodate those units, Mayor London Breed instructed the Planning Department to expedite a rezoning plan.

“She saw the numbers and said ‘We gotta get going,’” Yalon said. “What usually happens in two years we did in eight months through an insane amount of outreach, surveys, in-person meetings.”

The Planning Commission’s meeting on Thursday lasted hours and featured a few dozen speakers, several of whom represented neighborhood groups opposed to upzoning along with some standing in support.

“[The Planning Department has] not implemented the mandated increased tenant protections prior to pushing these upzonings forward,” said Jeantelle Laberinto of the Race & Equity in all Planning Coalition.

Kath Tsakalakis, a Lakeside resident and co-founder of the Lakeside Village Business Council, spoke in passionate support of the upzoning and called the renderings shown at Wednesday’s meeting “ridiculous.”

“Upzoning was shown using literal lego bricks. Another rendering showed San Francisco returning to 1950s brutalist concrete monstrosities,” Tsakalakis said.

“No one at the town hall yesterday seemed to grasp how the law of supply and demand impacts price and affordability,” Tsakalakis added.

Earlier this week, Housing Action Coalition, along with San Francisco YIMBY and eight other pro-housing organizations, co-authored a letter to Breed’s office supporting expanding rezoning to facilitate the development of more mid-size apartment buildings in various parts of the city.

Planning officials are working on a new version of the rezoning proposal that, in keeping with Breed’s directives, prioritizes denser housing near commercial and transit zones. While the exact details of the rezoning plan may change, the roughly 82,000 units mandated by the state will not.

At Wednesday’s meeting, District 4 Supervisor Joel Engardio—who had to walk a tightrope on his positions on development—put a positive spin on possibilities like affordable housing and apartments on corner lots but he was often shot down by the crowd.

“I want people to see that change is coming and it’s something that people should accept because it could help those with real-life needs,” Engardio said in a phone call on Thursday. “[Neighborhoods United] is a volunteer group and they can say whatever they want to say, but what was most disappointing was the pushback on affordable housing.”

Wednesday’s gathering was the latest of several “Town Hall” meetings that have drawn packed crowds among residents skeptical of the city’s rezoning efforts. The next meeting will be in District 2 this fall, Brooke said.

District 7 Supervisor Myrna Melgar listened in the crowd but departed before the meeting concluded. “These are not my people,” she told The Standard in a text ahead of the meeting.