With all due respect: The San Francisco Botanical Garden may be nature, but it’s not nature nature. It’s engineered nature.

But Janet Kessler is here, like she is many mornings or evenings, looking for real nature — nature that belongs here, even if a lot of people don’t think it does. Kessler is looking for coyotes, as she has done just about every day, dawn and dusk, since 2007, when she appointed herself the documenter of the city’s packs.

On her blog, Kessler, 74, writes extensively about how the animals live, and how we should live with them. She has names for them and keeps track of the 100 or so living in more than a dozen family units, from the Presidio to Golden Gate Park to Glen Canyon Park. On this August evening, she walks by hastily posted signs warning of coyotes in the area. She points out the grove where “the incident” occurred — the incident that prompted the appearance of all the signs.

A few weeks before, a coyote in the botanical garden bit a 5-year-old who got too close to her den. Afterward, officers with the U.S. Department of Agriculture killed three coyotes.

Kessler is frustrated by the whole thing. “We humans shape who the coyotes become by our own behaviors,” she told me, and imparted her mantra: “Love their wildness at a distance, and let them be wild.”

Kessler, aka “the Coyote Lady,” is beloved or notorious, depending on whom you ask. On one hand, she has worked with Bay Area scientists, but she’s no scientist. She’s also vocal in her critiques of the city, as in the killing of the three coyotes. She wrote on Instagram (opens in new tab), “Right now, San Francisco [Recreation and Parks Department and animal control] are senselessly and systematically trapping and killing, one by one, an entire family of coyotes in the Botanical Garden for its natural protective denning behavior.”

Deb Campbell of San Francisco Animal Care and Control objects to Kessler’s characterization, pointing out that when a human gets bitten, her agency turns it over to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, which in turn calls in the feds: the USDA. After the USDA shot the coyotes, they matched the DNA from one of those coyotes to DNA recovered from the girl’s bite. “An entire family was not killed,” she said. The whole incident is a window into the complex levels of bureaucracy — local, state, and federal — involved in even a minor case of animal management, which in turn complicates the story of who takes responsibility for urban wildlife, and how.

“This was awful and heartbreaking,” said Campbell, “but it was out of our hands.”

One of the problems that Kessler, government officials, and researchers all agree on is that people want coyotes to conform to human notions of how they should be — to be more like the engineered botanical garden.

Campbell knows just how hard it is to control the behaviors of two unpredictable species — especially when they have access to deli meats.

“We had a case several years ago where we did a stakeout, and we actually caught somebody who had been feeding trays of meat daily to a coyote near Lake Merced,” she said. “Cooked meat. It got catering every day!”

Animal Care and Control officers caught the coyote feeder, and the district attorney charged them, recounts Campbell. But the case was thrown out by a judge “who didn’t see the importance of not feeding coyotes.”

The outcome? “That exact coyote was taken out of the botanical gardens a few years after this case, because it was stalking toddlers and going up to children, and it charged at a child.” That coyote, shot dead by a sniper in 2022, was a famous critter named Carl (opens in new tab).

Campbell’s job is tough, because she has to set expectations about normal coyote behavior: following dogs, nipping dogs, “escorting” humans away from dens. But Animal Care and Control is an organization designed for the ease and comfort of humans, not nonhumans, so when there’s an “incident,” the coyotes tend to lose out.

After a trip around the botanical garden in which no coyotes were seen (but a trio of unleashed dogs charged her), Kessler explains that the best way to deal with coyotes is not to interfere — a tall order in the third-densest city in the U.S. “I am trying to understand them and relate to them” on their own terms, she said. “Hey, they’re living their own lives.”

Creation myths of the SF coyote

You could say that in San Francisco, coyotes are a fairly recent innovation. They’ve been here since approximately the dot-com bust: 2002 or so.

The last time they were here was a century ago. As agriculture and ranching expanded in the West, poison was used as a land-management tool; that, along with urban growth and habitat loss, pretty much eliminated coyotes from the Bay Area in the early 1900s.

Then came an unlikely hero: President Richard Nixon, who in 1972 signed an executive order (opens in new tab) banning the use of sodium monofluoroacetate, known ominously as Compound 1080, which had been used to kill coyotes that preyed on sheep on federal grazing land. (It killed a lot of other animals, too, which is why it was banned.) After that, the coyotes began their cautious return into Marin, the East Bay, and finally, San Francisco.

“And then all the stories are, ‘Coyotes are invading these areas,’” said Ben Sacks, director of the Mammalian Ecology and Conservation Unit at UC Davis. “Well, they’re not actually invading them, because they’re just coming back.”

Sacks would know. His lab has been studying them since they came back around.

In the early 2000s, coyotes were seen in the Presidio, the first in the city since 1925. In 2003, a researcher for Sacks’ lab (opens in new tab) trapped one, collared it, and took samples. The collar failed, and the coyote disappeared, but its DNA matched that of coyotes from north of the bridge. So, how did it get here? The answer, once again, involves human interference.

There are two main theories for the return of the coyotes.

The first is that they crossed the Golden Gate Bridge. (That’s what Sacks’ study concluded.) The second, usually told by researchers with a smirk or a sigh, involves a bogeyman: a trapper who brought coyotes down from the northlands.

“I just heard the same stories you may have heard,” Sacks told me, “which is that there was some trapper in Mendocino County that thought he’d show those liberals that banned leg-hold traps.”

Indeed: a revenge tale. Over the years, this mysterious trapper has become legend, a kind of Johnny Appleseed scattering wild canines across the West.

Whatever the case, coyotes have spread across the city in numbers that are not definitively known. Another mystery: whether the current population is related to those Presidio colonizers, or if others sauntered up from the Peninsula.

That’ll be a future study by Monica Serrano, a Ph.D. candidate in Sacks’ lab. She’s doing genetic testing on scat and tissue samples and working up a family tree for SF’s coyote population. One thing she’s looking at is the level of inbreeding.

“We haven’t seen much in terms of physical mutations in the coyotes, so it’ll be at least good to kind of see how much inbreeding is starting to build up in the population,” she said.

Inbreeding is one risk of an isolated urban population. Motorists are another. SF Animal Care and Control collects 30 coyotes a year that are killed on roads. Beyond that, though, it’s a stable population, meaning generation after generation is raised amid the ecological, geological, and sociological quirks of San Francisco.

The animals have personalities and preferences that they pass on to their young. Sometimes they eat a dog or a cat, or bite a kid on the butt. In the novel, one-of-a-kind ecosystem that is San Francisco, this may be unusual, but it’s not unnatural. Quite the opposite.

It’s more like ‘human versus human’

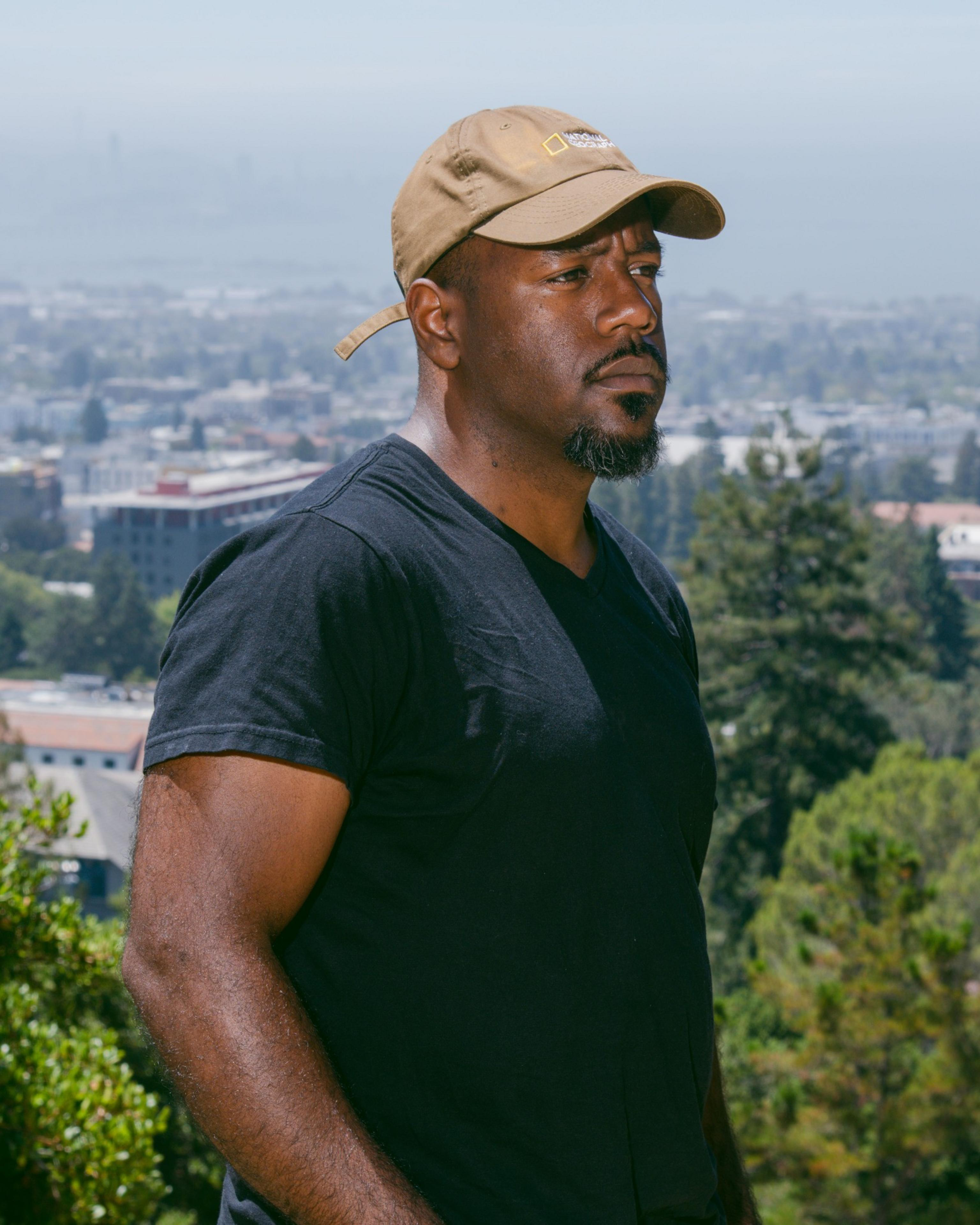

At UC Berkeley, Christopher Schell runs a lab (opens in new tab) that studies how city life shapes the modern coyote. With trail cameras set at 102 sites in SF and the East Bay, his lab has learned many things. But one of the big ones is that coyotes are not all the same.

Berkeley coyotes, for example, are shy. “They are happy to be around people; they just don’t want to be seen by people,” he said. “And, you know, contrast that to some of the coyotes that are in SF, and they can give two shits, man. Those animals are as bold as bold can be. And one of the developing studies we have right now with these camera traps is measuring how different these animals actually are.”

Incidents like the recent bite saga cause a flurry of hand-wringing, because the implicit assumption goes something like: Now that one has gotten a taste for human flesh, they’ll all eat our kids. While coyote researchers understand the concern, they get frustrated that the public tends to oversimplify things.

That’s how you get two extremes expressing opinions in the Bay Area: the people who worry that coyotes are unnatural in the city and should be removed, and the people who love and feed them. Both are versions of controlling nature; consequently, both lead to conflict.

As Christine Wilkinson, a globe-trotting biologist who works in Schell’s lab, puts it: “One thing that is often part of the work that I do is recognizing that most human/wildlife interactions, especially conflicts, are actually human/human interactions that are playing out in relation to wildlife.”

‘Nothing is pristine’

Will we ever get used to pack carnivores hanging around the Ghirardelli factory, or will it always seem a little weird? That’s what the urban ecologists studying coyotes are dealing with — a relatively young field of study that sounds paradoxical to the average urbanite. Cities are where nature isn’t. So urban ecologists are about studying the reality, which is, of course, that nature is everywhere, and a city is what’s called a “novel ecosystem” — a natural construct not like anywhere else.

“I think, historically, ecologists in the foundation of the field didn’t view urban ecosystems as valuable in terms of conservation, in terms of study, because everything is human-manipulated,” said Tali Caspi, a researcher in Sacks’ lab. She has studied the diet of SF’s coyotes, collecting scat from across the city and figuring out what-all they’re eating: a lot of chicken (served as, say, a McNugget or cat food), a lot of rodents, the occasional cat. People are coming around to the idea of there being value in collecting coyote poop for the insights it may yield into this unique place.

“Obviously, there’s been a shift, as we’ve come to realize nothing is pristine,” Caspi said. “Nothing is untouched by people, anywhere.”

That’s not all bad, though. Caspi has a nice vision of how it could be.

“Something that I think is so cool about urban ecosystems is, you can go to Saint Mary’s Recreation Center at like 6:30 in the morning, you can see that coexistence in action: where ladies are working out, minding their own business; the coyotes are teaching their babies and feeding them and playing with them, minding their own business; and the staff is maintaining the site. It’s in those moments where I’m like, this is so cool, because if the world is continuing to urbanize, we want cities that look more like this — where that scene can just happen everywhere.”

Clarification: An earlier version of this story presented a quote suggesting that Animal Care and Control shot three coyotes. The Standard has added a response from the department clarifying that the USDA was responsible for shooting the animals.