On Lombard Street, just downhill from the corkscrew turns, a dozen tourists mill around and take photos. Parrots fly overhead as a sightseer poses in front of the apartment building where Kim Novak found Jimmy Stewart in “Vertigo.” In the middle of the block, trucks are parked at a gray-walled estate, and workers hammer away. They’re fixing Sam Altman’s place.

The billionaire OpenAI co-founder purchased the Russian Hill property in March 2020 for $27 million. The estate features two turn-of-the-century residences, an infinity pool, and a huge ultra-modern addition, on a choice plot that was part of an $83 million real estate shopping spree (opens in new tab). Although Altman got it for a relative bargain — it was first listed at $45 million — ownership has not been quite what he bargained for.

In July, gleeful reports in all manner of news publications (including this one) presented the most attention-grabbing allegations in a lawsuit filed against the developer of the property, Troon Pacific, and its contractors over what amounts to shoddy construction: water leaks, sewage spills, and hazardous mold. Altman’s attorneys all but ensured publicity by characterizing the estate as a “lemon,” the result, they said, of cost-cutting by an unscrupulous developer.

Behind the headlines is the story of a property that has long been associated with San Francisco’s wealthy and powerful, as well as one controversial, iconoclastic genius. As the estate transforms for its next chapter, its previous iterations recede further into the background. But they, too, have secrets to tell about the evolution of the city and the oligarchs who have always fought over its most precious commodity.

Wealth in the wilderness

Russian Hill rises 360 feet above sea level on San Francisco’s north side. It was named for the Russian sailors who, moved by the views and unable to use the Catholic cemeteries, buried their dead at its southern peak in the early 1800s. (Whether the small cemetery (opens in new tab) was removed or built over decades after being discovered by ’49ers remains a mystery.)

Five things we learned from our bare-all interview with Sam Altman

From the beginning, the north slope was one of San Francisco’s elite districts. After the U.S. took San Francisco from Mexico in 1846, land within the city limits as far west as Larkin Street was sold on a first-come, first-served basis. It cost about $16 for a sixth of a city block — as good a deal as San Francisco would ever know again.

The estate that would become Altman’s “lemon” was first developed in 1864 by Sylvester Hemenway, a merchant who built a house and connected the water supply. Twenty years later, the Wright family, who came to San Francisco in 1860 from Mississippi, moved there. Remarkably, the lot has the same dimensions today as it did then.

The Wrights joined other wealthy residents — attorneys, engineers, and physicians — who built gardened homes in the neighborhood, especially once horsecars and cable cars arrived to ferry people uphill.

Selden Wright was a prominent lawyer and judge. His wife, Johanna, was involved in heritage organizations and founded the first chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy west of the Rocky Mountains. They had 12 children.

When Wright died in 1893, the Bar Association of San Francisco wrote that “it was in his home and among his family and intimates that our friend appeared at his best and drew all hearts toward him.”

A temporary shack at the end of the world

For all its wealth, Russian Hill was not safe from cataclysm.

Early in the morning of April 18, 1906, the great quake struck and broke the city’s water mains. A fire spread from South of Market to northern neighborhoods, jumping breaks made by soldiers using dynamite. The city burned for 72 hours. By the end, the Russian Hill neighborhood, including the Wrights’ home, was destroyed.

Reconstruction began, but lumber was scarce and expensive. Still, the widowed Johanna Wright didn’t want to leave.

A newspaper report from July 1906 noted that she was “so deeply attached to the site and the view it commands that she intends returning to live there as soon as possible, even though she may not have time to erect more than a temporary shack.”

While living in a quickly erected cottage, the family enlisted the famous Chicago firm of D.H. Burnham & Co. to design a house for a cool $4,950. The company was busy rehabbing its pre-1906 skyscrapers and other downtown San Francisco buildings, but business is business.

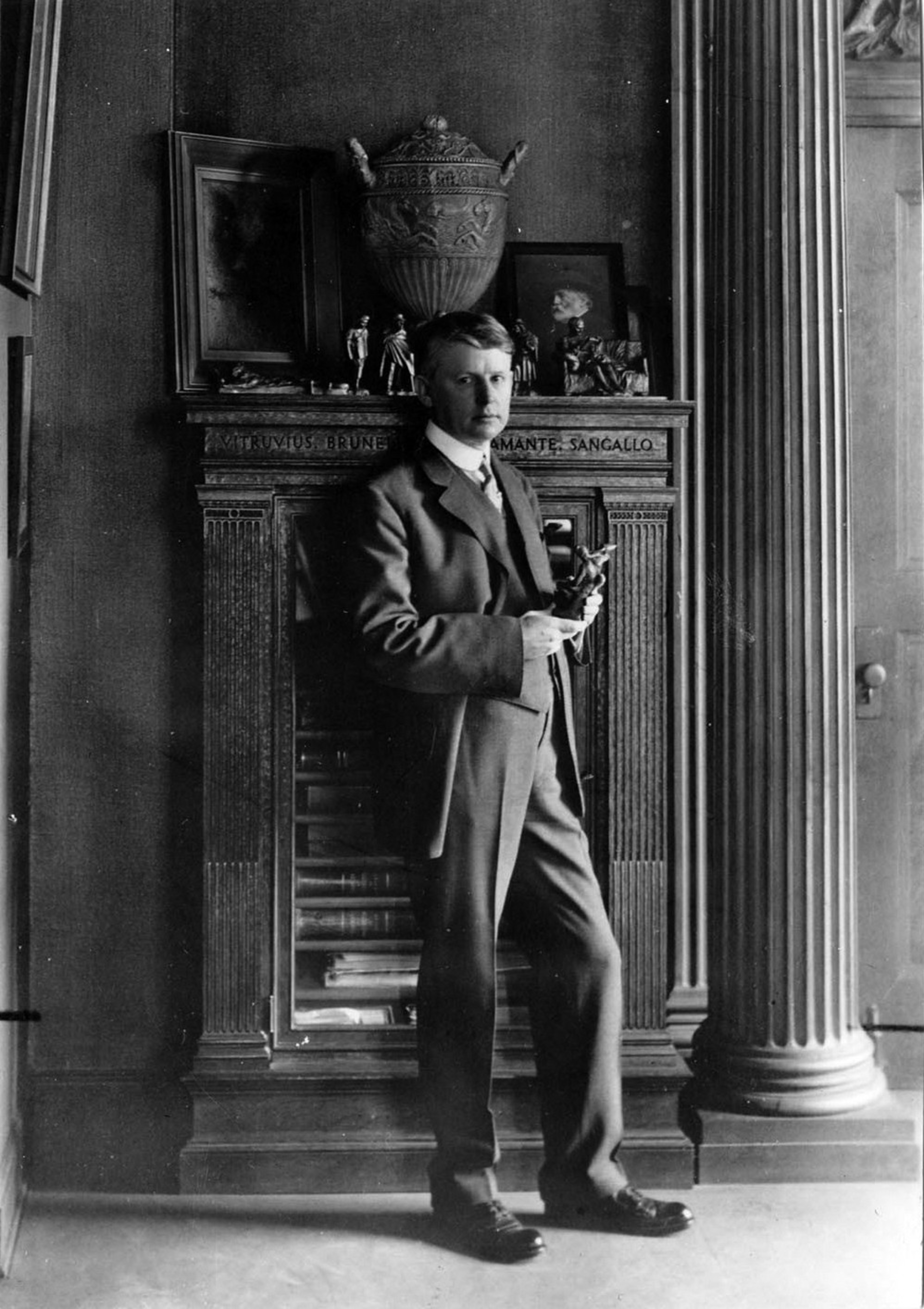

Running the reconstruction effort was Willis Polk, a San Francisco name-brand troublemaker.

Polk has been described as the enfant terrible of San Francisco architecture. Living on Russian Hill in a seven-story house he designed, he was an outspoken critic of buildings and politics. He once dressed as a woman to parody the suffragettes. Yet he harbored a deep interest in civic beauty.

“I think he sort of cultivated the bad-boy image, especially earlier in his life, in the 1890s and early 1900s,” said Richard Longstreth, who documented Polk’s career in the book “On the Edge of the World.” “And even after that, he was not a responsible husband, shall we say. He drank too much, and he died of syphilis.”

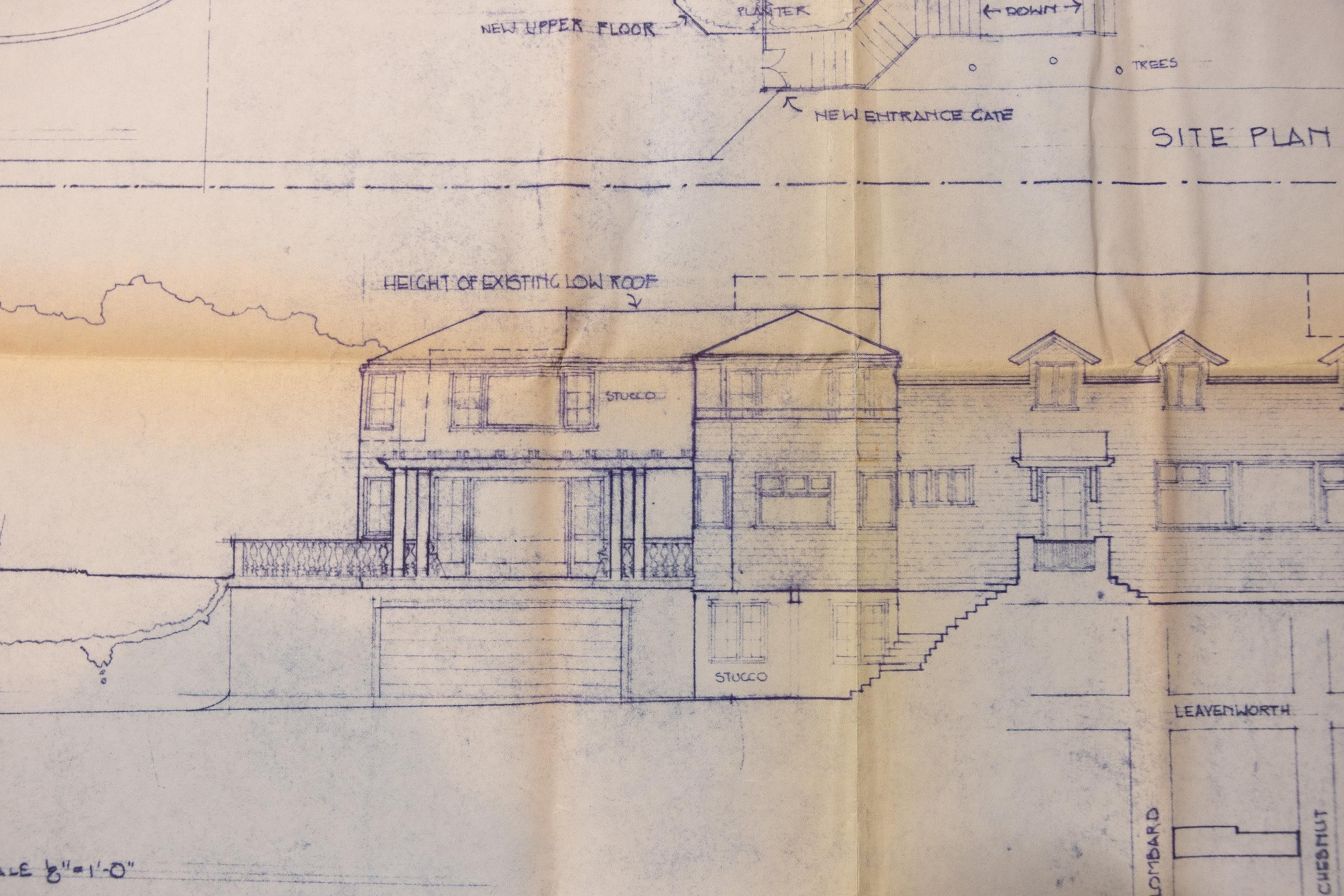

Built in the San Francisco First Bay Tradition or “shingle style,” the new Polk-designed house was set at the rear of the lot overlooking Chestnut Street. Johanna Wright moved in, but on Jan. 10, 1909, the Board of Health noted that the residence was built on sand or loose soil rather than bedrock and required that cement be laid. She defied the order.

“This house is built on rock, and according to the saying in regard to such houses, is going to stand firmly. So am I,” she told a reporter.

Johanna continued to be a regular presence in the news until her death in 1919.

Corporations call it home

Wrights lived at the estate until 1977. It passed through several generations until the death of Helen “Nannie” Wright ended a family saga of more than a century on Russian Hill.

After that, the estate’s modern mogul years began. Susie Tompkins Buell and Doug Tompkins, founders of the outdoor apparel company the North Face, lived on the property around 1978 and turned it into a hub of corporate do-gooding. Tompkins used it as a conference center for his charitable foundation until around 1992.

Later, the main house became a residence for the president of the board of governors of the San Francisco Art Institute, which is across the street. Parties were held to welcome contemporary artists.

But by the mid-1990s, the property was empty, and modernization plans began to circulate by its new owner, a trust. In response, preservationists worked to cement its status as a historic landmark. Neither happened.

Fast-forward to the modern tech era. In 2012, luxury developer Troon Pacific and its CEO, Greg Malin, bought the property for about $4.5 million. Malin thought the location was perfect for an uber-modern spec home — something that could be sold to, say, a tech billionaire.

Troon Pacific soon drew fire from neighbors, preservationists, and lawmakers for defying its building permit and demolishing much of the Polk-designed building. Today, virtually nothing of the legendary architect’s structure remains.

Outcry over the project led to the city attorney issuing an injunction and ordering the company to pay a $400,000 fine, the largest ever in San Francisco for such a violation. It didn’t matter. As hot as the real estate market was in the 2010s, those penalties were just speeding tickets on the road to huge profits.

The preservationist group SF Heritage held up the project as one of the “most egregious examples of demolition by serial permitting in city history.” Perhaps not surprisingly, this was just before the city’s Department of Building Inspection got turned upside down by federal indictments. A lot of the focus landed on Bernie Curran.

Curran was a senior inspector with the Department of Building Inspection who resigned in 2021 in anticipation of federal and local corruption charges. He had a habit of assigning himself inspections and would perform as many as 20 a day. Curran and two other DBI employees who ran afoul of the law — Rudy Pada and Cyril Yu — worked on the property, records show.

The estate, once associated with old-school SF influence and, later, fashionable fleeces, became a symbol of corruption in the city’s bureaucracy.

“The DBI that existed during the time that the [property] was being permitted and inspected was completely out of control,” former Planning Commission member Dennis Richards told The Standard. “Those in management positions thought that they could operate however they wished for connected developers.”

Steps have been taken to prevent such a thing from happening again, according to the planner. “However, the jury is still out on how successful those reforms will actually be.”

Hammering away the past

In 2018, after four years, a dozen permits, and more than a dozen complaints, the spec home was completed and listed for $45 million — 10 times the purchase price. The property now looks like someone airlifted a charming cottage onto the roof of a cement bunker. It is outfitted with an infinity pool, a wellness cottage, and a garage with a “Batcave”-like tunnel.

Later that year, Board of Supervisors President Aaron Peskin cried foul. He put forward an ordinance to increase the penalties for demolishing more than permits allow, in an effort to curb bad behavior by developers.

“[Troon Pacific] bent every rule in the book,” Peskin told The Standard, “and whether they had inside help from corrupt building inspectors, I don’t know. But it wouldn’t shock me.”

In May, Troon Pacific was ordered to return $48 million to investors in four other luxury properties.

And now, the hammering and drilling continues as the property at 950 Lombard St. once again takes a new shape. It’s a long way from a grave for Russian sailors or the fires that nearly killed the city, but still — always — very close to the city’s center for wealth, power, and influence. Maybe it won’t resemble its origins, but it very much looks like a product of modern San Francisco.