In San Francisco, there are places where you can go for a steam, a sauna, and a cold plunge. And then there are places you can go to have steamy sex with strangers.

But surprisingly, there’s not a place to do both — well, legally.

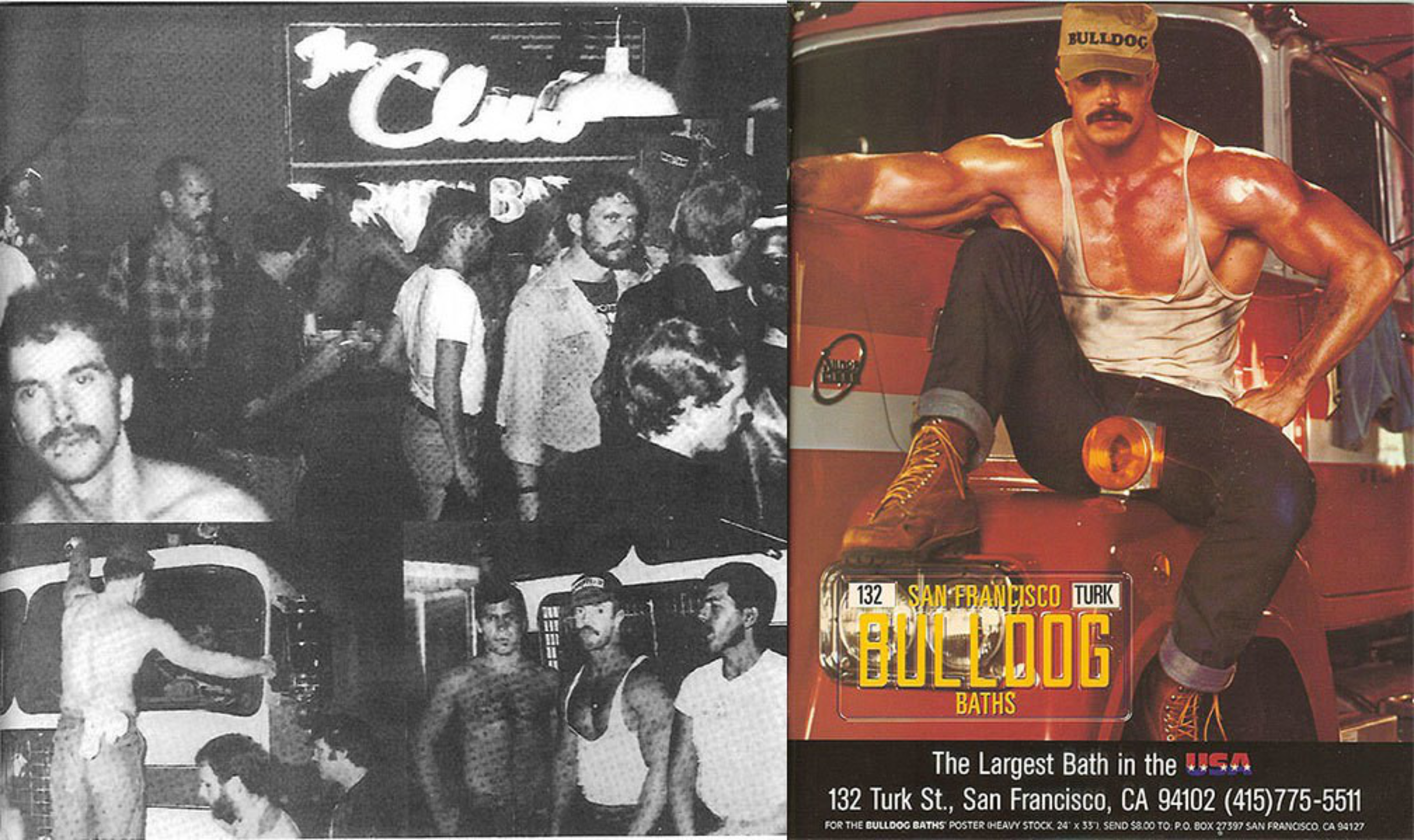

San Francisco was once famous for gay bathhouses like Ritch Street Health Club, the Barracks, and Bulldog Baths. These operated in a legal gray area, with authorities generally turning a blind eye but periodically conducting raids for “lewd conduct.” In the 1980s, fears over the role the venues played in the spread of HIV/AIDS led to a court order (opens in new tab) that made it nearly impossible for the businesses to survive.

None have operated within city limits since 1987, even as an uber-kinky festival with its own waterworks takes place annually on Folsom Street.

Supervisor Rafael Mandelman, a gay man who represents the Castro, has been on a multi-year crusade to get bathhouses steaming again. It’s been a history lesson on how outdated mores have wormed their way into a complex bureaucracy.

“We’re gonna try to make these happen,” Mandelman said in an interview. “Or at least ensure that the city is not the barrier to this happening.”

His first try was unwinding restrictions (opens in new tab) on the operation of gay bathhouses in the city’s health code, a legacy of the AIDS crisis. He followed that by changing the planning code to allow bathhouses and sex clubs to operate in a larger swath of the city. Most recently, he’s attempting to remove the ultimate authority to regulate and permit these businesses from the San Francisco Police Department.

Mandelman introduced legislation Tuesday that would repeal Article 26 of the police code, which outlines standards around sanitation but also requires businesses to keep a registry of all patrons and prohibits services from being offered behind locked doors. The hope is to get the law passed by the end of the year.

In a rare bit of San Francisco comity, pretty much everyone is on board. The Department of Public Health was already responsible for much of the Article 26 oversight, and a stretched police department was happy to get it off its plate. Police found themselves ill-equipped to answer questions about waterproofing and what exactly counts as a prohibited “service.”

What goes on inside a sex club may be the stuff of feverish imaginings, but the business of running one is more prosaic, particularly in San Francisco, where red tape is less a bondage prop and more a fact of life.

Although the Tenderloin queer sex club Eros features a glory-hole alley, video play areas, and a handful of sex slings, what’s top of mind for co-owner Ken Rowe in running the 30-year-old business are his real estate footprint, throughput, and the rising cost of insurance.

Over the years, he’s seen several efforts try and fail to spin up a bathhouse in the city. One of Rowe’s biggest outstanding questions is about utilities. With prices through the roof and the state in perpetual drought conditions, who can afford to fill, clean, and refill pools?

“There’s a reason why we describe ourselves as a sex club. We’re not trying to confuse people,” Rowe said. “But we’ve always said we do better when there’s more choices.”

The allure of reviving bathhouse culture in a gay mecca — paired with a city government trying to make the process easier — has inspired locals to try their hand.

One of the most prominent efforts in the works is from Joel Aguero, who is fundraising (opens in new tab) the $3 million necessary to open Castro Baths. Aguero, a former employee of The Standard, said Mandelman’s legislation would eliminate a key hurdle for the nascent business.

“Supervisor Mandelman and his office are removing a significant blocker to the permit process, accelerating the opening of Castro Baths,” Aguero said in a statement.

Initially, the plan was to open by June 2025, but Aguero told the Bay Area Reporter (opens in new tab) that timeline is unlikely, given that no lease has been signed.

Nathan Diesel, another would-be bathhouse operator, has scouted several locations in SoMa, including a commercial property near the intersection of Howard and Dore streets. He estimates conservatively that it would take at least $1.5 million to make his dream a reality.

Diesel, a regular patron of Steamworks Baths in Berkeley, had his eyes opened during a recent 50th birthday trip that included a tour of European bathhouses.

“In the European model, you can order apple pie and a sandwich and hang out. It’s a completely different vibe,” Diesel said. “The fact that we have a bathhouse across the Bay means we have business that’s actively leaving San Francisco.”

Over the summer, Diesel conducted a survey (opens in new tab) that found enthusiastic support for his idea. And he believes that with the city struggling in its pandemic recovery, it’s worth throwing anything at the tiled wall and seeing what can stick.

Make bathhouses gay again? It just might work.