Two competing visions over how to tackle the homelessness and drug abuse crises are dividing elected officials, residents, and activists on San Francisco’s east side — all over just 42 units of housing.

At the center of the battle is 1174 Folsom St., a building the city hopes to soon fill with LGBTQ youth between the ages of 18 and 24 who are coming from homeless shelters or transitional housing.

But just as it is about to cross the finish line, a disagreement over whether to evict tenants who use illegal drugs is sparking a dust-up.

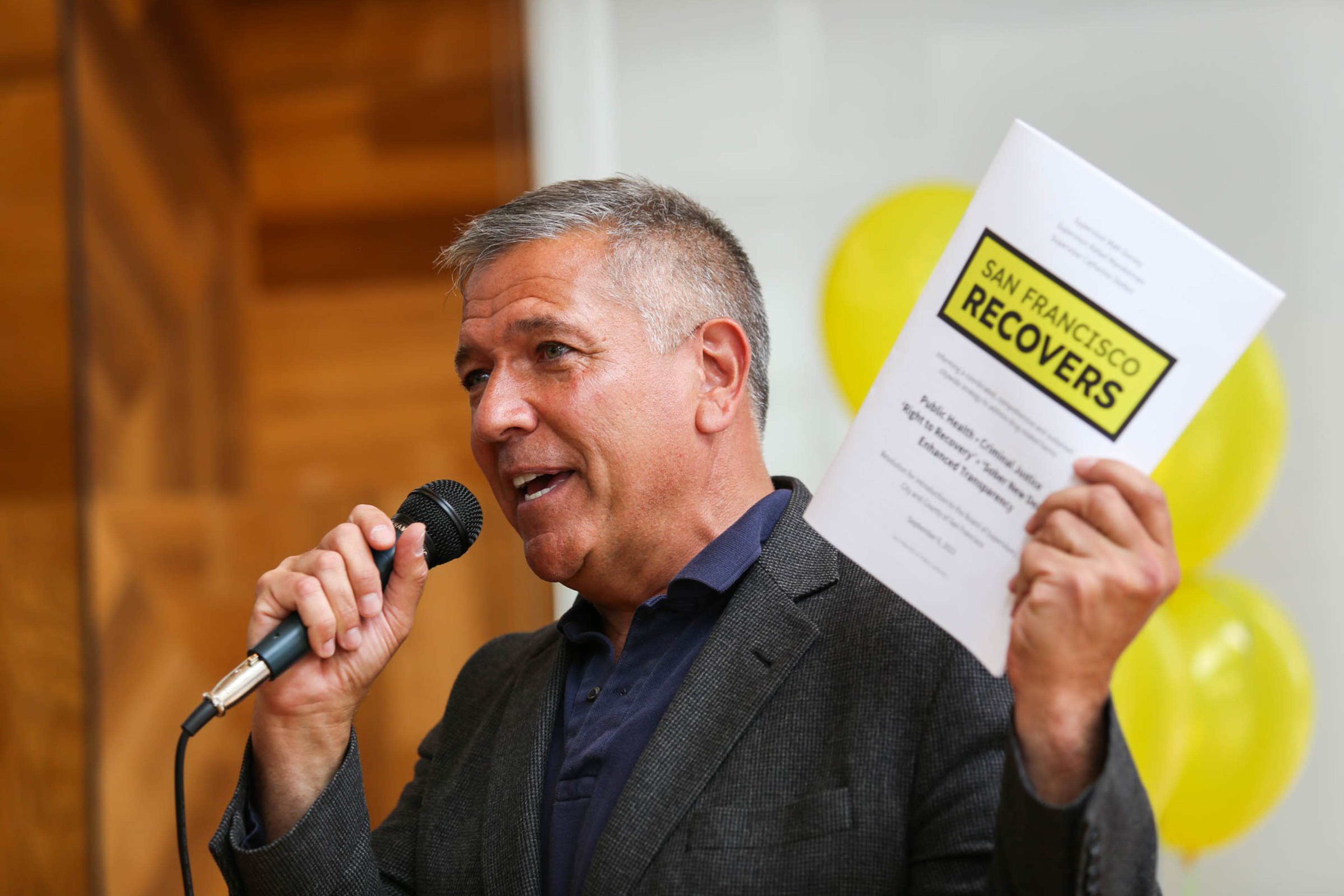

The west SoMa neighborhood has become a hot spot for open-air drug dealing and crime, residents say. Some are siding with Supervisor Matt Dorsey, arguing that there are insufficient rules to ensure that the Folsom housing remains drug-free. The group is advocating for additional anti-drug language in the project’s paperwork.

“SoMa has become a dumping ground,” said Ryan Zin, co-owner of Bay of Burma, a restaurant on the bottom floor of the Folsom Street project that has been the site of multiple armed robberies. (opens in new tab)

Others, including the property manager and homelessness nonprofits, claim the current leasing rules do not allow for drug use and that Dorsey is trying to delay the project. They say the housing clients are escaping conservative areas of the state and country that have passed anti-LGBTQ laws — and claim drug use shouldn’t be a significant concern.

“That’s not at all this population,” said Gael Isaiah Lala-Chávez, executive director of LYRIC, the on-site service provider. “This population is literally trying to survive.”

The disagreement reflects a wider ideological skirmish on San Francisco’s streets.

Academics and activists have long argued that the best way to combat homelessness, drug use, and mental health crises is to get the street population under a roof — a philosophy known as the “housing first” model. The idea is that once people are housed, regardless of their drug habits or other behaviors, many of the underlying issues can be addressed.

But another school of thought, one that has gained momentum under Dorsey and Mayor London Breed, is a push for housing environments in which drug use is prohibited. The issue is a personal one for both officials: Dorsey is a recovering addict, and Breed lost a younger sister to an overdose.

The effort comes as thousands of San Franciscans have died from overdoses in recent years, mostly due to fentanyl, a drug that many officials and experts say has changed the game when it comes to fighting illegal substance use. Additionally, the city is clamping down on public camping after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in June that local governments have the power to be stricter on homeless encampments.

“I’m all for housing first,” said Keith Humphreys, a Stanford professor who was a drug policy expert for the Obama administration. “We have very good evidence that living in a clean and sober environment is really good for people’s health.”

“And,” he said. “A lot of people need recovery.” Humphreys emphasized that illegal drug use doesn’t harm just the individual but can have a detrimental impact on others.

In February, Breed proposed a sober living facility in Chinatown that would have been a first-of-its-kind model. The project’s intention differed from the Folsom Street facility, as it would be exclusively for residents in recovery. Residents wouldn’t face drug testing, though multiple relapses would mean a transfer to another type of housing.

In that case, pushback came from Chinatown neighbors, who said they weren’t properly consulted and publicly confronted Breed with their concerns. The project was nixed at the Chinatown location. A spokesperson from the mayor’s office said the city is close to finalizing a contractor for the project at a different site but did not disclose a location.

In SoMa, residents who say they were promised a drug-free facility on Folsom Street claim the city has reneged. The project will have on-site security and community ambassadors.

While the lease agreement between the future tenants and Abode, the property manager, includes a provision prohibiting illegal drug use, the ground lease and grant agreement have contradictory language that opens the possibility for the behavior to be tolerated, neighbors say.

Dorsey has been advocating for additional language prohibiting drug use, arguing that it will protect the city if the property manager does not obey the no-drug policy.

Supervisor Connie Chan, who chairs the budget committee, confirmed that the project will be discussed at a Dec. 4 meeting.

“I think we’re undermining our progress if all we have is, ‘Listen, we’re just harm reduction, no judgment on people’s drug use,’” Dorsey told The Standard. “I’m not against that kind of housing, and I’m not against housing first. What I’m for is we should have some categories that are drug-free for people who want that.”

Emily Cohen, a spokesperson for the San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, told The Standard, “Now is not the time for finger-pointing, it’s time to house young people as we have the building ready and the providers selected. It’s time to move forward together.”

Dorsey’s fight with homeless advocates spilled into public view Monday after the supervisor posted on X (opens in new tab) messages from Coalition on Homelessness leader Jennifer Friedenbach.

The nonprofit head, who has become a lightning rod among critics of the city’s homeless strategy, described in an email to advocates that opposition to the Folsom facility came from “very hateful neighbors” and urged them to get involved in pushing back against the project’s critics.

In an interview, Freidenbach blamed Dorsey for not getting the site up and running faster.

“He is kowtowing to NIMBYs in that area who don’t want more people there,” she told The Standard. “Why is he allowing people to suffer?”

Dorsey said he envisions a policy in which tenants are given more than one chance if they’re caught using illegal drugs on the premises. “It wouldn’t be automatically evicting people,” Dorsey said. “It’s more about offering services, drug treatment, residential treatment, and then a second chance.”