On the northern slope of Bernal Heights, amid bay windows adorned with rainbow Pride flags and leftover signs supporting Aaron Peskin for mayor, sits a 66-student school that weaves in lessons from the Bible with deep study of classical creeds and languages. Though it’s attended by kids whose families represent a cross-section of San Francisco, it was co-founded by a conservative Christian tech investor who has made no secret of his support for Donald Trump (opens in new tab) and his hard-right views on immigration (opens in new tab), homosexuality (opens in new tab), and abortion (opens in new tab).

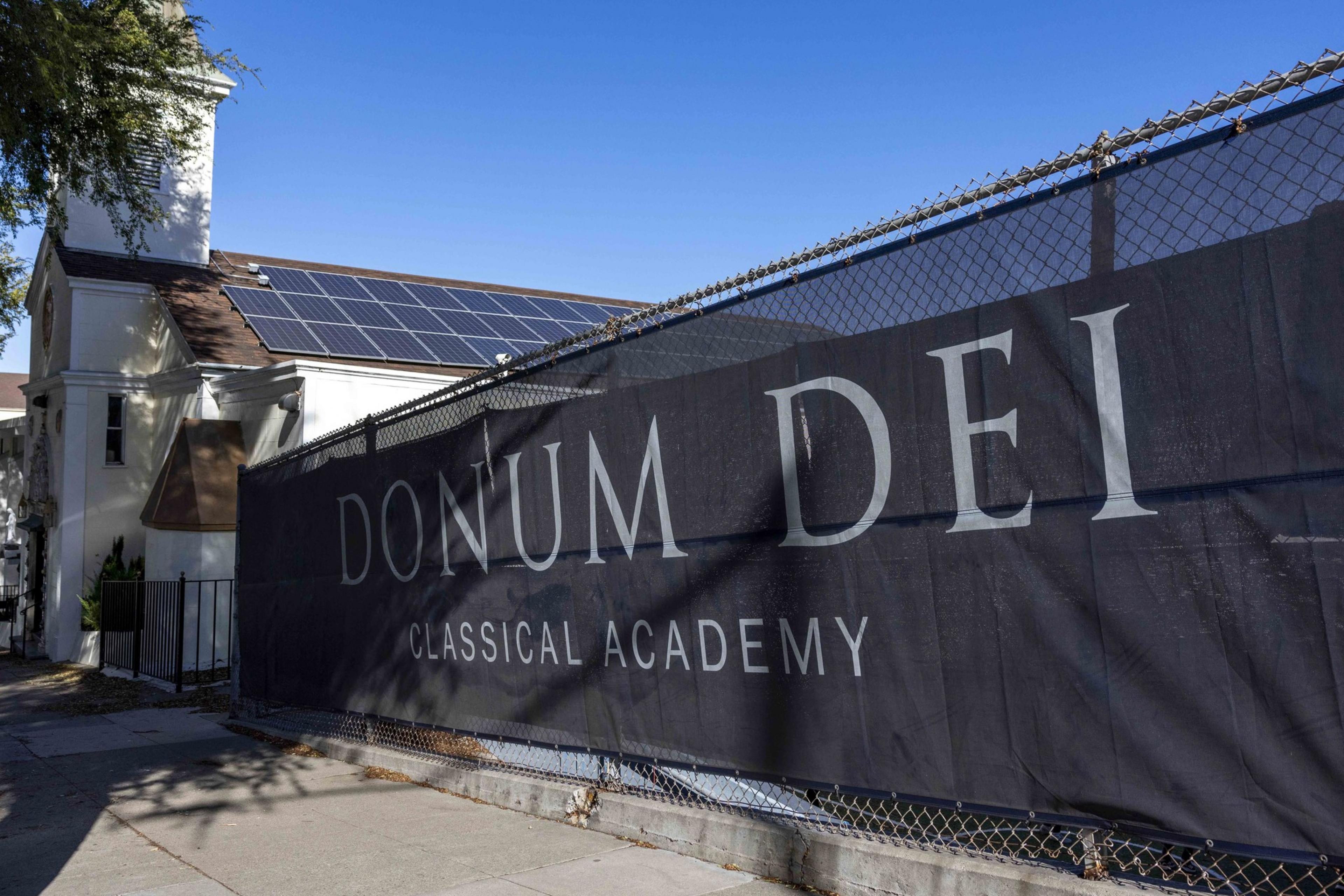

Donum Dei Classical Academy “exists to be a gift of God to the families and churches who call San Francisco home,” according to the school’s website (opens in new tab). “We seek to impart a rich classical Christian curriculum full of Scriptural truth and life-giving experiences … in the hands of our godly, experienced teachers and education partners.”

Far from being a solitary conservative island in a roiling sea of secular progressivism, Donum Dei’s influence is expanding. The small school has grown by roughly 25 students since opening in 2019, and revenue from anonymous contributions increased from $45,692 that year to $773,319 in 2023.

And it’s not the only religious school gaining ground. While enrollment in public schools continues to plummet, classical Christian schools — which combine classical liberal arts training with Christian doctrine — are blooming around San Francisco. Of the four classical Christian schools The Standard identified in the city, three opened in the last five years. Nationally, the number of such schools grew 4.8% in the same period, according to data compiled by consulting firm Arcadia Education.

Donum Dei was founded in 2019 by right-wing venture capitalist Nate Fischer and his wife, Meghan, who live in Dallas. The other founding partners are West Portal residents Christine and Colin McLean. Christine, who serves as the board chair, previously worked at Christian institutions in Texas and at the University of Texas at Austin. Colin is chief revenue officer at Digital Realty, an Austin-based real estate investment trust with offices in San Francisco.

The McLeans declined a phone interview with The Standard, while the Fischers did not respond to requests for comment.

While Nate Fischer has called himself a Calvinist, his ideology and investment portfolio are much closer to those of Dominionism, which promotes a society governed by Christianity and biblical law. “I think that we have a dominion mandate to fill the earth, to subdue it, to take dominion,” Fischer said in an interview (opens in new tab) with the conservative think tank American Moment.

The venture capital firm he founded and runs, New Founding, has an explicit mission (opens in new tab) to fund companies with conservative values that will reinvent the U.S. “through a partnership of the new ‘political right’ and an emerging ‘tech right.’”

As a part of its efforts, New Founding has invested in Armanet, an Oakland-based ad platform that aims to bypass advertising restrictions on the firearms industry, and Presidio Healthcare, a pro-life medical firm based in San Diego that fits the “criteria for Catholics,” Fischer said in the American Moment interview. Presidio’s goal, he added, is to “build an entirely new network of doctors that don’t require Covid vaccines, for instance, or aren’t going to trans your kid.”

A former fellow at right-wing think tank the Claremont Institute, Fischer leads a secretive Christian fraternal society (opens in new tab) and has founded an ammunition company with federal contracts (opens in new tab), according to The Guardian. According to the Federal Election Commission, he donated more than $14,000 to Republican candidates in the past two election cycles, including $2,900 toward the senatorial campaigns of J.D. Vance in Ohio and Ted Cruz in Texas. Fischer has blurbed books arguing for the importance of Christian nationalism and diligently promotes self-proclaimed Christian nationalist Doug Wilson — considered the father of classical education — on his podcast (opens in new tab) and in the publication (opens in new tab) he co-founded, American Reformer.

Though he speaks often about the values of classical Christian education, Fischer is nowhere to be found on the Donum Dei website. When asked about the Fischers’ involvement in the San Francisco school, Christine McLean emailed that the founding couple “live out of state and have little recent affiliation with our school.” Tax filings show that Nate Fischer stepped down from the board after the 2020-21 school year. McLean said Meghan Fischer exited the board this year.

Yonahandi Vaca, a social worker whose child attends Donum Dei, said she had never heard of the Fischers. But she said her family loves the school they co-founded. “We chose it because it aligned with our Christian belief,” she said. “I feel like they have a fresh approach on education. I had never heard of classical, and that was really attractive to me: learning things the old way, with cursive and Latin.”

A blossoming movement

In addition to Donum Dei, which teaches kindergarteners through eighth-graders, San Francisco’s classical Christian schools include Nativity High School, which opened this fall with 20 students in the Inner Richmond; Saint John of San Francisco Orthodox Academy, a 25-student K-8 school in the Richmond that opened in 1994; and Stella Maris, a former Catholic school on the same campus as Nativity that has doubled its enrollment to 86 students since reinventing itself in 2021.

Unlike Saint John, which offers a classical education rooted in Orthodox church teachings, and the Catholic-leaning Nativity High and Stella Maris, Donum Dei is not affiliated with any sect of Christianity. The Catholic and Orthodox schools do not require students to be members of those churches, but Donum Dei requires a “covenantal partnership” wherein at least one parent is involved with a Christian church, with a note from the parishioner to prove it. In effect, this means non-Christians aren’t welcome at the school.

At a recent information session for prospective parents, Donum Dei Principal Trisha Mammen described the school as part of a movement to “recover the liberal arts,” asking parents, “What worries you about educating your child in San Francisco?” A reporter from The Standard attempted to attend two publicly advertised information sessions for Donum Dei but was asked to leave after identifying himself as a journalist.

According to faculty and administrators, classical Christian schools largely appeal to parents who want notions of tradition, faith, and conservative values woven into the curriculum. At Stella Maris, one of the city’s fastest-growing classical Christian schools, “woke books” are culled from the library through a “triage” system, said Marilyn Bridon, an art teacher and assistant to the head of school. Students there attend Mass on Fridays and are incentivized through scholarships to get involved in their parish.

“We certainly don’t talk about pronouns in our school,” Bridon added.

At Donum Dei, STEM and humanities studies are guided by faith — “God as the mathematician and the scientist,” Mammen said at the information session for prospective parents, according to education consultant Tiffany Claflin, who was in attendance. When asked by Claflin if students are taught creationism, Mammen responded, “God made earth and man. We did not come from slime.”

Such teachings are not embraced by other local parochial schools, including Catholic schools, which, under the guidance of the Archdiocese of San Francisco, do not teach creationism. “We teach what science can prove,” said Peter Marlow, a spokesperson for the archdiocese.

“A lot of people in our community have said it’s important to them that we’re not too far out there, too far to the left,” said Helen Sinelnikoff-Nowak, an administrator and teacher at Saint John of San Francisco Orthodox Academy. “I’m not preaching to parents, but I hear them, and that’s what they’re looking for.”

Families flocking to these schools appear to reflect a yearning for stability and tradition. The emergence of classical Christian education in San Francisco may be less a full-scale cultural revolution than a bellwether of a city grappling with its ideological roots.

The movement aligns with San Francisco’s gradual turn to the right in November’s local (opens in new tab) and national (opens in new tab) elections. The percentage of city voters who cast ballots for Trump increased from 12.8% in 2020 to 16.7% in 2024. The results of ballot propositions, including the overwhelming passage of Proposition 36, which reclassifies some misdemeanor drug and theft crimes as felonies, and the failure of Proposition 6, which would have banned forced prison labor (opens in new tab), also reflect a statewide tack to the right.

“In my experience, there are a solid number of parents looking for a school like this,” said local education consultant Vicky Keston, who works with parents navigating the public school lottery and private school admissions processes. She estimated that 10% of her clients are interested in Christian education. “Some parents prefer questions about gender identity to be taught at an older age and for young children not to be actively suggested that they reconsider what their gender is. These parents would prefer schools to focus on academics over politics or social justice.”

San Francisco was once the least religious U.S. city, but earlier this year, it fell behind Seattle (opens in new tab), according to data from the ongoing Household Pulse Survey, a product of the U.S. Census Bureau. Tech, the Bay Area’s main industry, has embraced religion.

Classical Christian schools fuse Christian ideology with the curriculum of “trivium” — a focus on grammar, logic, and rhetoric that has roots in ancient Greece. They teach the “Great Books” (opens in new tab) and pride themselves on small class sizes. They also pride themselves on what they don’t teach: diversity, equity, and inclusion; gender ideology; and, in some cases, evolution.

“Parents don’t want kids exposed to outside influences that are prevalent in our city,” Bridon said. Asked if Stella Maris teaches critical race theory, the administrator blanched. “We don’t teach that,” she said. “We teach Latin, though.”