In the early 1980s, a rubbish-picker sifting through an abandoned storage locker in the Bay Area stumbled upon something incredible: a plastic garbage bag filled with 2,042 processed 35mm color slides and 102 rolls of carefully labeled black-and-white film. The images — all 8,417 of them — captured a seminal moment in San Francisco counterculture, from 1966 through the 1967 Summer of Love to 1970.

The photographer remains unknown, and most of the photos have gone unseen — until now.

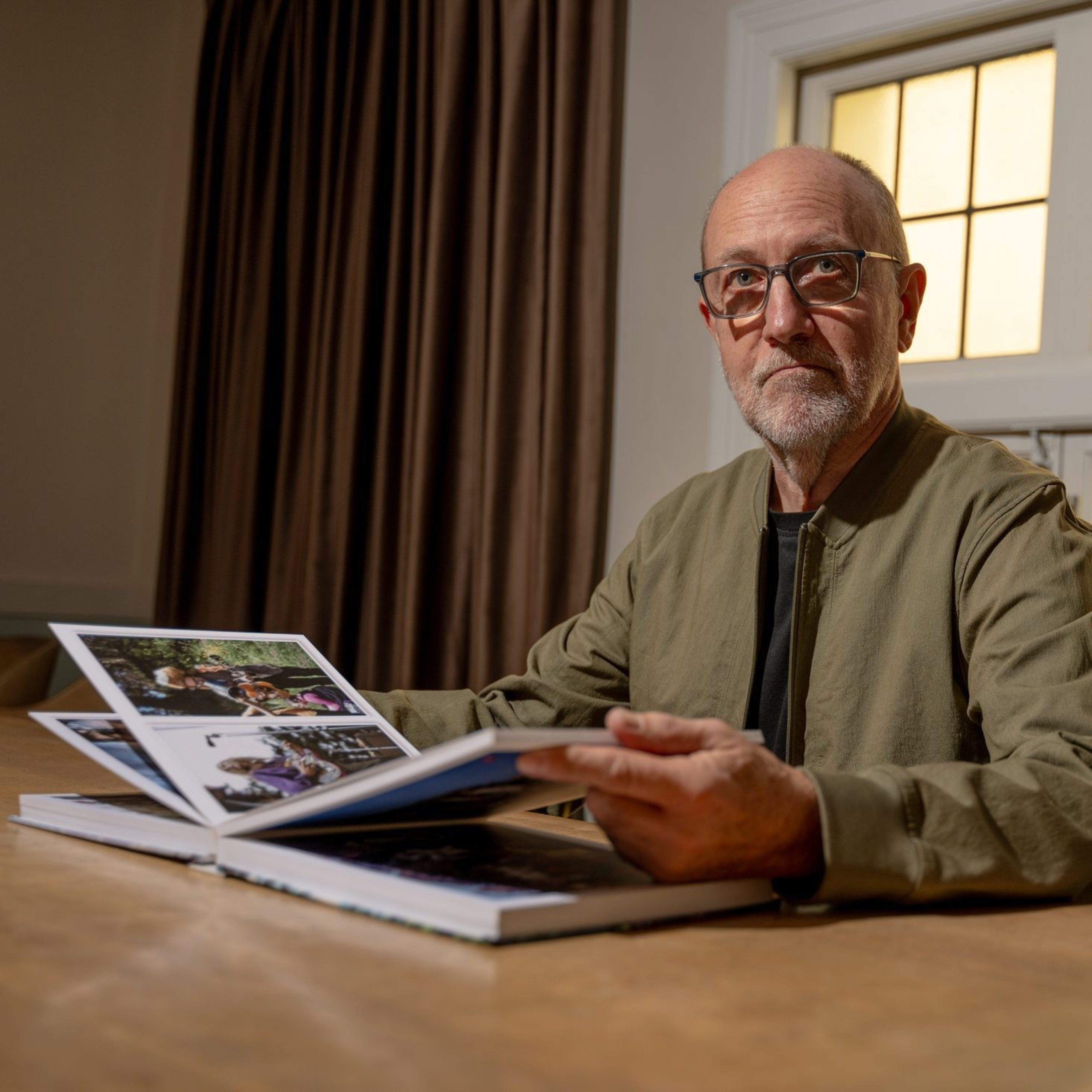

“It’s just a heartbreaking loss to think that someone would have spent five years documenting this and never even had the opportunity to see half of the work,” said Bill Delzell, a photographer who took ownership of the photographs, along with the task of developing them and researching their provenance. “Usually, we run straight back to the lab, but for this photographer to have held onto the work for as long as they did before they lost it — that’s where the mystery lies.”

Delzell, who runs a nonprofit teaching children about photography, was contacted in 2022 by collectors who purchased the photos, which had changed hands several times since being found in the storage unit. The collectors’ identities were not revealed to The Standard, but Delzell said they had developed all the black-and-white photos and sold the collection to him to develop the remaining 75 rolls of Kodachrome color film — around 2,700 photos. They sold the lot for an undisclosed amount.

Delzell is two years into his mission, in a project he calls “Who Shot Me — Stories Unprocessed.” He is puzzling over questions of the photos’ provenance and unknown creator. “How could they have been disconnected from this work?” he asks. “What happened? These are all questions we’re trying to answer.”

Working with a film restoration company in rural Canada, researchers from the Internet Archive, students from a Sacramento charter school, and, perhaps, someone reading this article who may have clues, Delzell is intent on uncovering the stories behind the photographs, preserving them for public access, and above all, finding the missing photographer.

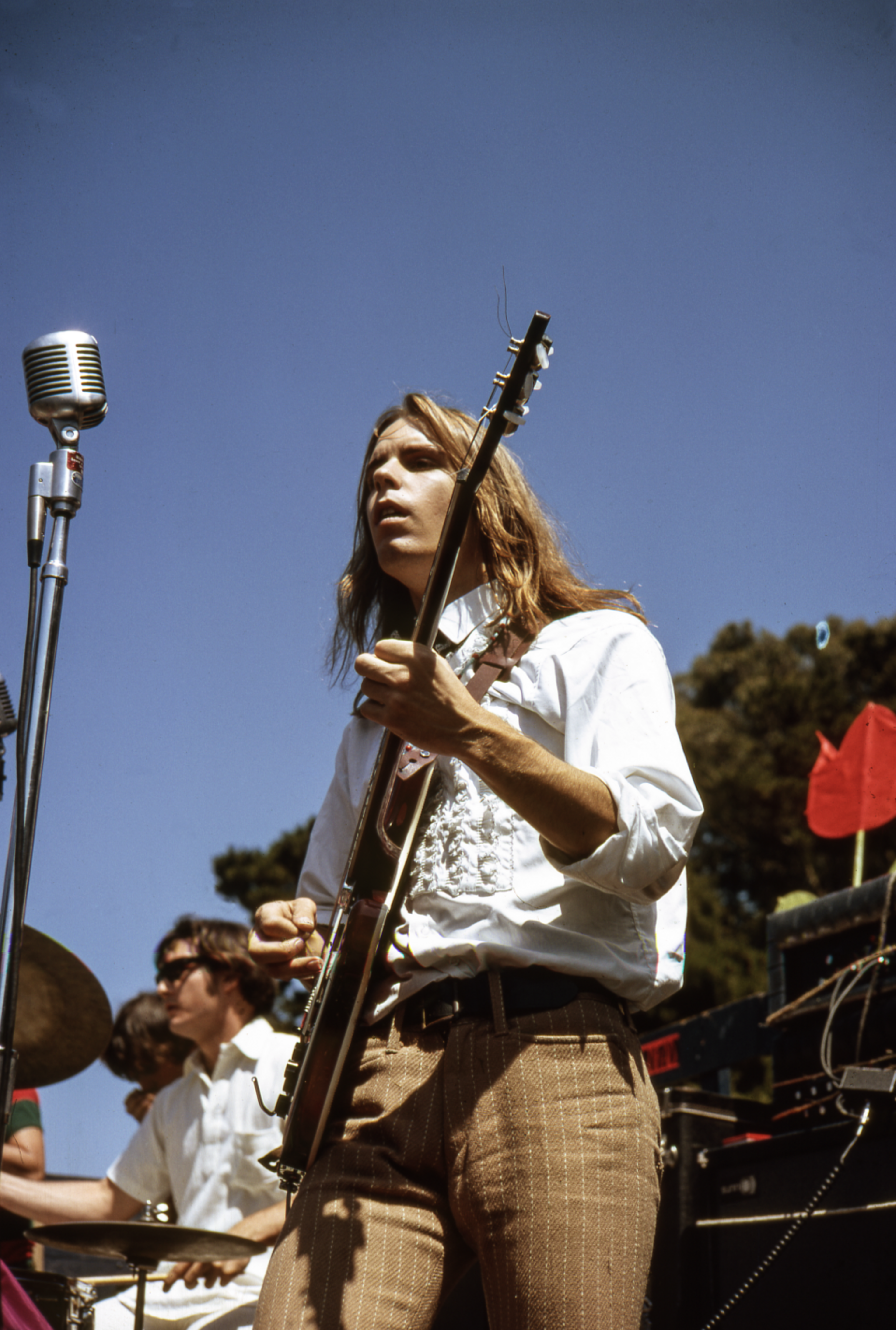

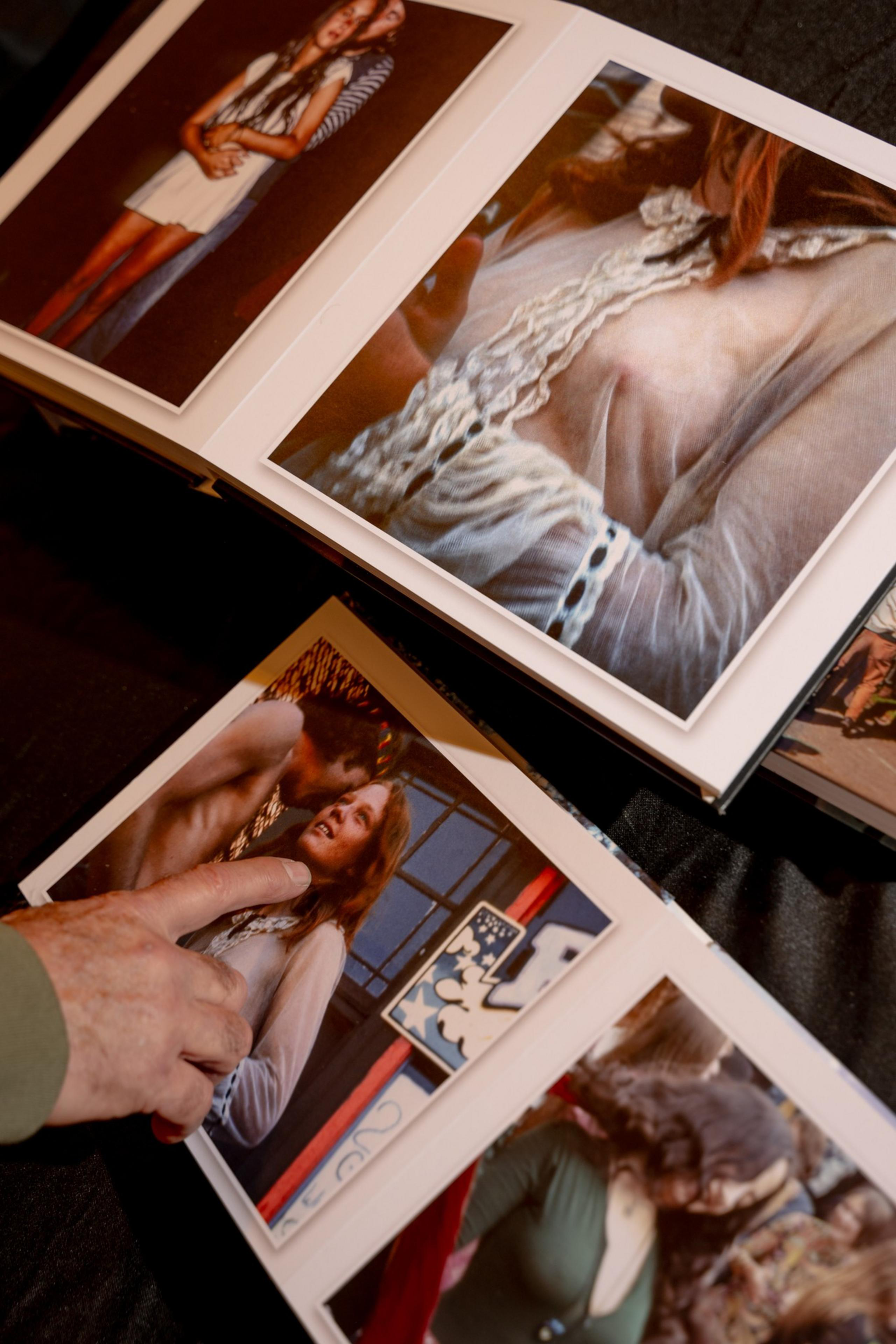

The photos capture historic moments in bursting color. There’s a 1966 American Nazi Party rally outside City Hall, an early Grateful Dead show in the Panhandle, Vietnam War protests, and gatherings in support of the United Farm Workers and the Civil Rights Movement.

Portraits of cultural and political titans were captured when their national relevancy was still budding. There are intimate shots of Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary, Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver, and Muhammad Ali, to name a few.

The photos also contain moments of quotidian magic for Delzell.

Shortly after the collectors recruited him to restore the remaining rolls of film, Delzell contacted a photography friend and Haight Ashbury native, Katy Kavanaugh, and texted her five random screenshots of already-developed color photos. One showed a scene from September 1968, in which farmworkers and residents were marching at the foot of Dolores Park, taking part in the five-year Delano Grape Strike (opens in new tab). She recognized that it was shot on Dolores Street and even saw people she recognized from her neighborhood.

“Then I see a couple with babies and kids in the stroller, and it’s my family,” she said. “My father is standing behind my mother, looking out into the crowd, and I look down and see myself looking at the scene, trying to make something of it. The weight of the moment is both in my dad’s and my face. It was clear that the photographer wanted to capture San Francisco in this moment, with children and families recognizing the plight of the farmworkers.”

Kavanaugh implored Delzell to send more photos.

Within minutes, she spotted a photo featuring her friend Stanley “Mouse” Miller, legendary poster artist for the Grateful Dead (opens in new tab), walking through the Panhandle beside a group of men and women who’d painted themselves orange, green, and blue.

It takes a village

It’s incredibly challenging to develop vintage Kodachrome film, requiring a specialized process that isn’t widely available. So Delzell has turned to Film Rescue International in Saskatchewan, Canada, renowned for developing vintage film (opens in new tab).

“Kodachrome film is something really special,” said Gerald Freyer, a film archivist for FRI. “It cannot be processed in color anymore, because Kodak and the chemical industry stopped making the dye transfer that brings the color to the Kodachrome film. What we can do is process it in black and white, and this process is adapted to these old and expired films.”

The color is sadly lost to history, Freyer said, and cannot be naturally recovered. However, he and his team have begun implementing artificial intelligence to recolor the photos — a tedious and finicky process, he said.

As the film is sensitive to the X-rays used across the United States mailing system, Delzell plans to drive to the company’s U.S. office in Westby, Montana, to deliver the film. From there, it will be driven across the border to Indian Head, Saskatchewan, to be developed.

Jeff Pollard, a social studies teacher at Natomas Charter School in Sacramento, has been assisting Delzell with determining the provenance of the photos based on visual clues in each.

“What I like about it is the intersectionality,” Pollard said. “The photographer doesn’t have a journalistic role as much as a participant — like an insider. It looks like the photographer hung out around an event and took photos of everybody there. You have Nazi counter-protesters, Hells Angels, the United Farm Workers, the counterculture kids, and you just have the neighbors walking through the park.”

One Natomas student, Amari Kiburi, 17, has made it his senior project to digitize a trove of photographs, several of which will be featured in a school exhibition at the end of the year and lay the groundwork for paid internship opportunities for students, Pollard said. Delzell has started a Kickstarter campaign (opens in new tab) to help pay for these internships and develop the photographs in Canada. Scanning 8,417 photographs, he said, will take thousands of hours and tens of thousands of dollars, with the ultimate goal of creating an accessible database available at the Internet Archive, a massive digital library built by a San Francisco-based nonprofit.

“My goal with Kickstarter is really to try and turn this into a community research project that can connect people … and learn something about the past through the lens of one photographer,” Delzell said.

Gallery of 20 photos

the slideshow

After two years of working on this project, Delzell has made little headway in identifying the missing photographer, but he has his speculations.

“It’s hard to imagine that the photographer is living,” he said. “No journalist or artist would let the images of such iconic figures knowingly sit untouched for so long, which suggests a student or an avid hobbyist. But the quality of the work is what’s so stunning.”

There is, however, one clue about the photographer’s identity. In one of the developed photos is a storefront window, decorated with an art nouveau scene. In a faint reflection, the photographer can be seen holding the camera to their face.

Delzell sees in the reflection a young woman, but the artist could be anyone.