San Francisco was in the middle of a political dogfight over the deadly fentanyl epidemic when drug activist Nova Schultz entered the public eye in the summer of 2023.

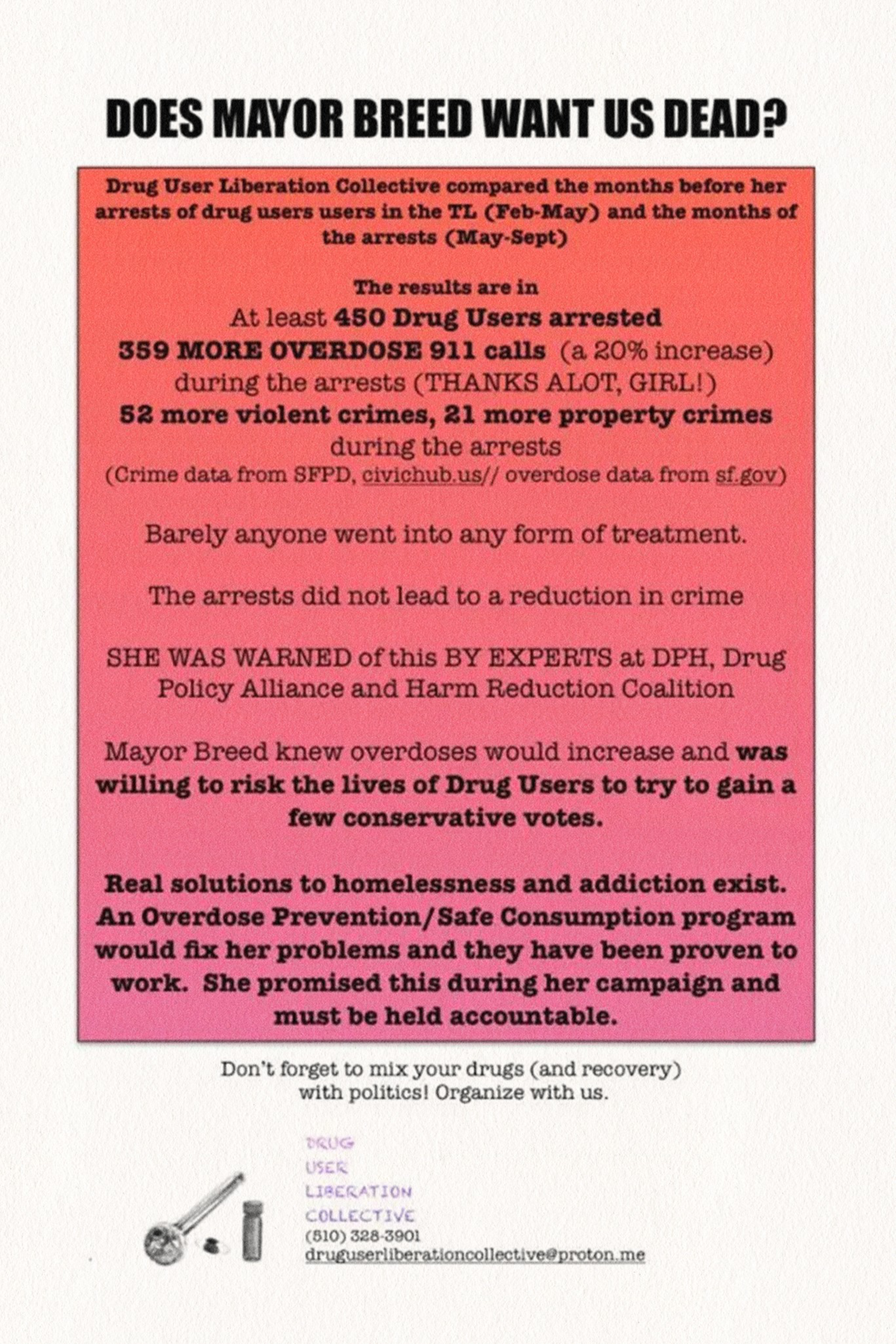

People were dying of overdoses at a record rate. Drug markets engulfed many downtown sidewalks. And for the first time in years, police were arresting people for using drugs after a crackdown began in the spring.

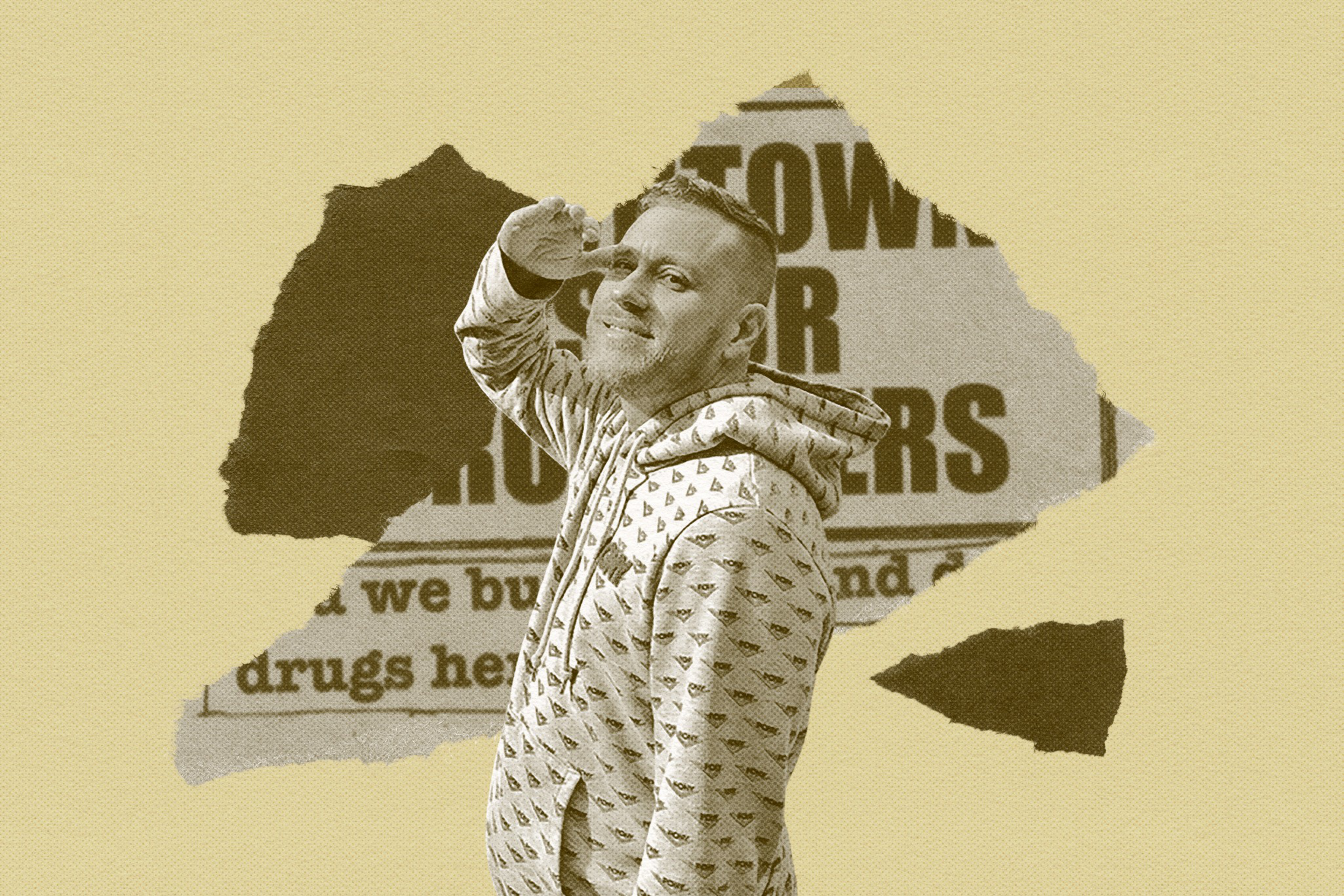

By Aug. 31 of that year, International Overdose Awareness Day, the city’s ideological factions were fuming over the crisis. That day, Schultz stood on the steps of City Hall, flanked by progressive politicians and nonprofit leaders, holding a homemade sign.

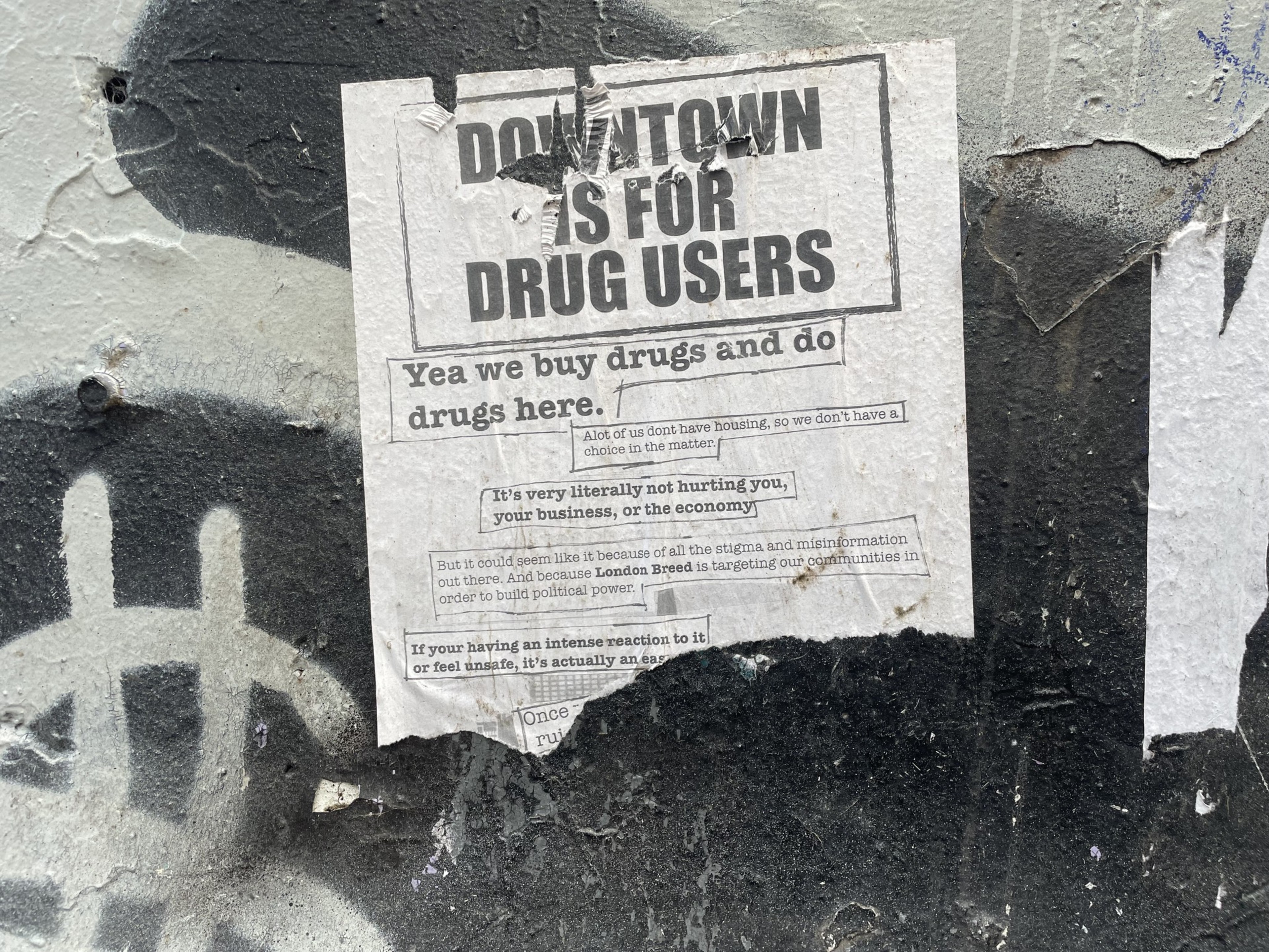

“Downtown is for drug users,” it read.

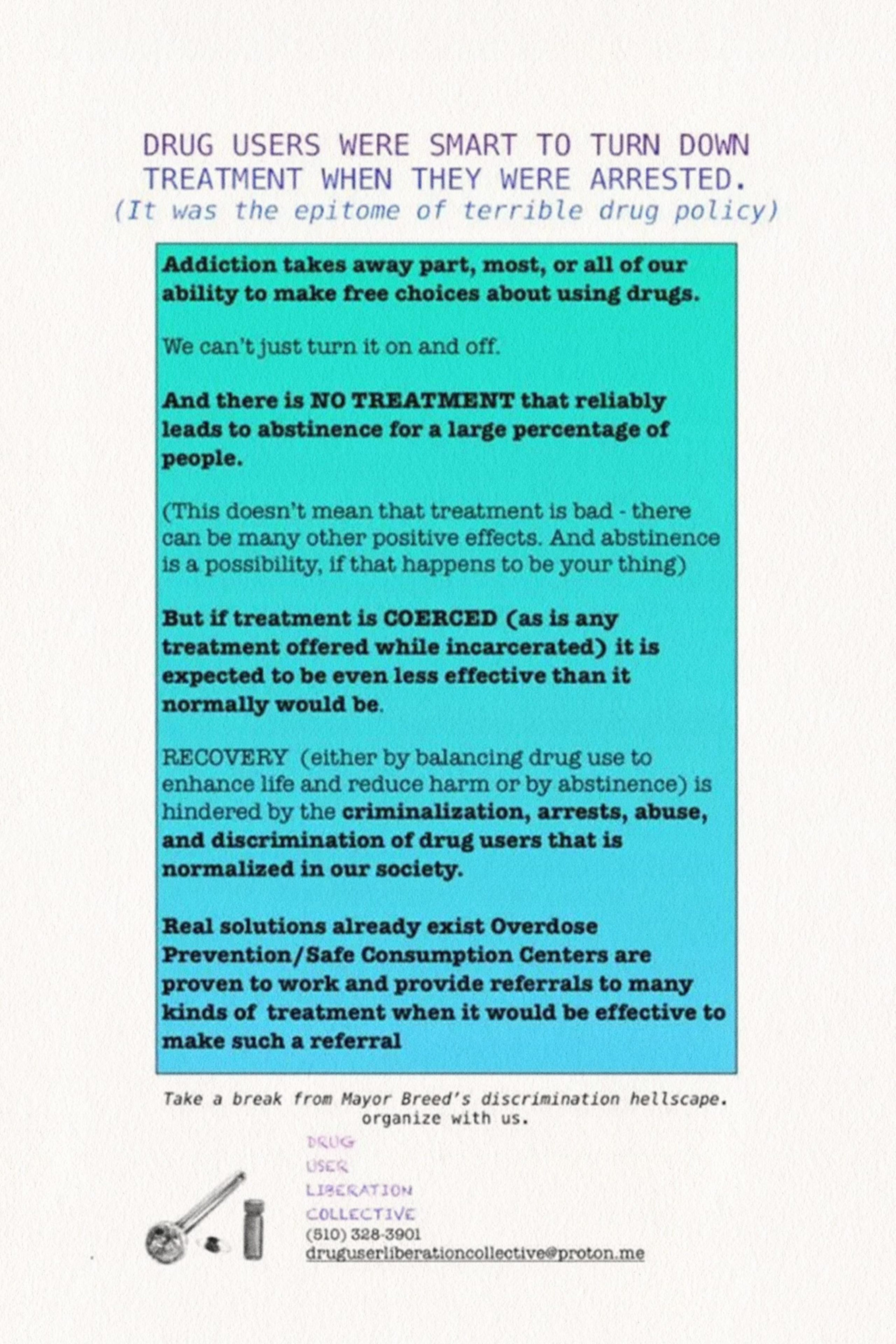

Images of the placard immediately went viral. Tenderloin leaders and online critics seethed over the message. But Schultz, always a provocateur, pressed on, hanging posters with the slogan around downtown and forming a coalition of like-minded activists, the Drug User Liberation Collective.

Schultz, who used they/them pronouns, said they hoped to sway the city from its shift to anti-drug policies. Ultimately, the opposite happened.

City leaders have since introduced a slew of drug enforcement measures. And on Oct. 30, at age 42, Schultz fatally overdosed on methamphetamine, anti-anxiety meds, and three types of fentanyl in their apartment at Sacramento and Polk streets, according to the medical examiner’s office.

They’re remembered by family and friends for their intelligence and generosity. But they were also known for their willingness to be controversial — a tendency that may have proved counterproductive in their campaign to win public sympathy for drug users.

“They liked shocking people,” said Andrea Schultz, Nova’s sister. “Sometimes that worked out really well for them. Other times it caused friction.”

‘A trailblazer’

Growing up in Kentucky, Nova was a talented piano player who graduated at the top of their high school class at 16, according to their father, Marvin Schultz. At 19, they moved to Cincinnati and were immersed in the anti-police riots of 2001. Later that year, they came out as gay and moved to San Francisco.

They couch-surfed and attended a master’s program for social work at UC Berkeley in 2011, according to Andrea.

They interned for the Drug Users Union, creating a healthcare guide for users. They appeared to be mostly sober at the time, said founding union member Isaac Jackson.

“They were a trailblazer,” Jackson said. “And they were very proud of their work with us.”

Friends and family aren’t sure when Nova became addicted to drugs. But in an interview with The Standard last January, they said they were a “drug user in recovery.” For 20 years, they had cycled in and out of rehabs, they said, fighting their addiction and the stigma associated with it.

They used their story to argue that many drug users are incapable of kicking their habit, and that legal persecution only worsens their condition.

“Our lives are inherently criminalized. It’s illegal to be us,” Nova said. “People who use drugs are not morally corrupt.”

Even as a practicing psychologist, Andrea is unsure what the answer is for people like Nova with severe addictions. Attempts by family and friends to confront Nova on their drug use often drove them further apart.

Nova severed relationships, cycling in and out of hospitals, rehabs, and housing. But still, they often told loved ones they thought they were immune to dying from drugs.

“I understood it wasn’t a decision I could make for them,” Andrea said. “Because if it was, I would have made them move home. I would have made them live in my basement. I would have said, ‘No fucking drugs.’”

That said, Andrea believes Nova’s radical understanding of harm reduction contributed to their demise. She said Nova was selectively leaning into certain principles in a way that was fueled by their own addiction.

“They didn’t want to stop. … It was almost like harm reduction gave them a license to use,” Andrea said. “I don’t think that from a policy standpoint, going back to abstinence-only and enforcing that alone is a good thing. But there has to be something between the form of harm reduction Nova practiced, and abstinence only.”

Even Jackson, who has spent much of his life advocating for the rights of drug users, said he was concerned by Nova’s habit.

“I thought fentanyl was extremely dangerous,” said Jackson, who only uses stimulants. “I kept asking them if they could somehow stop doing it.”

A few months before their death, Nova was evicted from a group home due to their drug use, Jackson said. They moved into a studio apartment, often using drugs alone. Jackson believes if they had a safer place to use, such as a safe consumption site, they may still be alive.

“That was the beginning of the end,” Jackson said.

In their last days, Nova’s body broke down, friends say. A final text message indicated they wanted to quit using. After they died, paperwork about a drug rehab was found in their apartment along with the body.

“They were an incredibly generous human being,” Andrea said. “But they lived hard. They always did. I accepted many years ago that I was going to get this phone call.”