Just a year ago, a state bill aimed at rolling back environmental review for new development solely in downtown San Francisco was deemed so politically toxic it never made it to a floor vote in Sacramento.

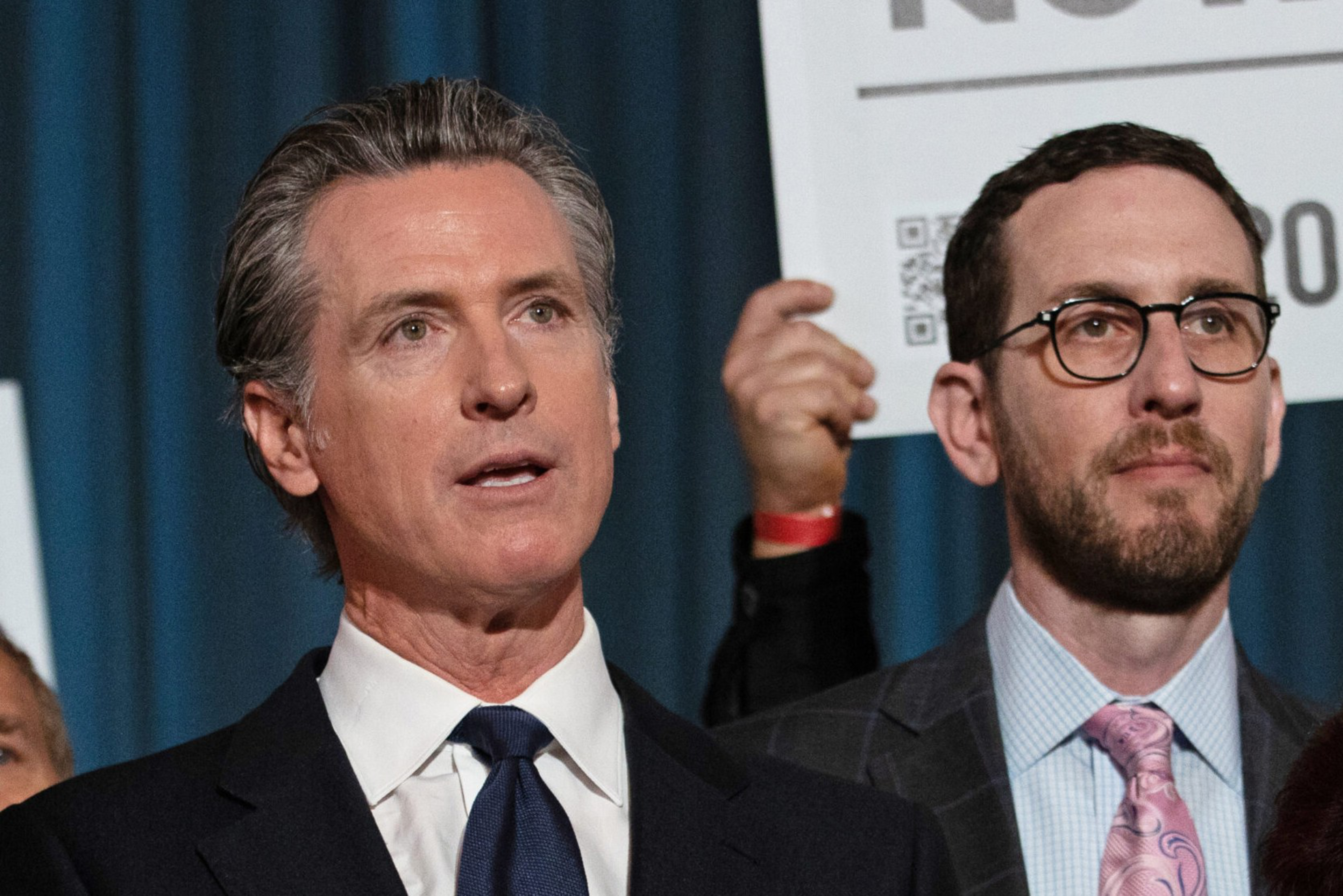

But last week, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed two bills meant to curtail the California Environmental Quality Act for certain new housing and infrastructure projects.

To hammer home just how much the discourse around CEQA has changed, Newsom called the new laws “the most consequential housing reform that we’ve seen in modern history in the state of California.”

“Go YIMBYs!” he said at a press conference June 30. “Thank you for your abundant mindset.”

In the YIMBY-NIMBY housing war that’s been brewing for more than a decade, CEQA — implemented by Gov. Ronald Reagan in 1970 — had become a whipping boy for the pro-housing coalition, which painted it as a well-intentioned law gone awry. Mechanisms meant to prevent unnecessary pollution or protect endangered species were instead used to stall much-needed housing production.

While Newsom’s messaging makes it sound as though CEQA has been wiped away, the effects of AB 130 and SB 131 are limited to carve-outs for projects in so-called urban infill environments. Any proposal that meets the criteria in the bills would be exempt from environmental review, theoretically cutting down the timeline and cost to get a project approved and built.

The new laws apply to projects that:

- Are smaller than 20 acres (five acres in the case of Builder’s Remedy projects);

- Have previously been developed or have a majority of the footprint adjacent to or nearby urban uses;

- Fit with planning guidelines, zoning ordinances, and abide by labor standards.

William Fulton, an urban planning policy expert, described the strategy lawmakers have taken to CEQA as a “Swiss cheese” approach, punching holes in the landmark legislation as new needs arise.

For example, state lawmakers passed a last-minute exemption last summer to clear the way for a renovation of the Capitol building’s annex. Same for the People’s Park ruling in Berkeley, which helped unlock a proposed 1,200-unit housing project that had been held up due to concerns from neighbors about the environmental effects of noise.

“The good part about [AB 130 and SB 131] is that they further the state’s overall policy direction of building as much as we can in dense places,” said Fulton, who publishes the popular urbanist newsletter The Future of Where.

“The downside is that it’s all very reactive,” he said. “Maybe we should take a step back and examine the purpose of CEQA as a whole rather than keep passing more bills.”

One of Fulton’s main critiques is that the law fails to address inefficiencies in the environmental review for “greenfield” developments — projects built on undeveloped areas. This week’s CEQA exemptions, for example, won’t apply to key infrastructure projects like the BART extension into downtown San Jose or the California Forever project in Solano County.

Still, AB 130 and SB 131 are the latest in a long line of reforms that local governments like San Francisco have undertaken to reduce friction for developers, said Andrew Junius, a land-use attorney at Reuben, Junius & Rose.

“It will take some time to sort through the nuances of the laws, but it’s yet another thing to keep the pressure on cities to make sure CEQA is not an impediment,” Junius said. “We’re telling our clients that this is simply good news. We just don’t know how positive this will be.”

Multifamily housing developers polled by The Standard struck a more measured tone. Tens of thousands of housing units in the region have been approved but never constructed, since financing and cost barriers are prohibitive. Moreover, even if a developer were able to skip the costly and time-consuming environmental impact review process, the risk of being sued later would remain.

“This will give pro-growth city leaders more cover to throw up their hands and blame Sacramento if NIMBYs get upset,” said a housing developer who requested anonymity to preserve working relations with local governments. “But anti-growth cities will still find ways to create speed bumps and road blocks.”

The laws, which were part of the larger state budget package, have already taken effect. Developers, attorneys, and city officials are still trying to parse the language and gauge the impact.

“The new streamlining provisions are complex, presenting both opportunities and obligations as well as special carve-outs unique to San Francisco,” said Dan Sider, chief of staff at SF Planning. He said the on-the-ground effects likely won’t be felt for months, until the department starts processing applications that invoke the new laws.

In a podcast interview with Derek Thompson, who cowrote the book “Abundance” with Ezra Klein, state Sen. Scott Wiener was asked how success would be measured given that California has passed many pro-housing measures, yet new construction remains scant.

“We’re very aware that the last five years have been rough,” Wiener said of supply-chain disruptions and high interest rates. “My view is that we need to get the rules right and in place so that when the economic stars align again, we can build a ton of housing.”