San Franciscans have long blamed lax traffic enforcement for deaths and injuries on city streets.

Politicians have reprimanded (opens in new tab) the cops. Angry San Franciscans have written to The Standard. And residents routinely take to social media to blast the “fucking lazy (opens in new tab)” police.

That came to a head last month when a civil grand jury castigated the San Francisco Police Department for its decade-long decline in traffic tickets.

The report (opens in new tab), which aimed to identify why the city failed in its goal of eliminating traffic deaths by 2024, acknowledged that many factors play into the issue. But it saved its most scathing language for the SFPD.

“Police leadership does not prioritize traffic enforcement,” the report says. “The result is the virtual abdication by SFPD of its essential role in keeping our streets safe.”

If San Francisco wants to achieve its Vision Zero goals, police officers will need to start doing their jobs, the jury wrote.

But The Standard’s analysis of two decades of traffic data shows little correlation between enforcement levels and the number of deaths or severe injuries of pedestrians, cyclists, and motorists. Experts, some of whom were cited in the report, agree that it’s unclear whether increased enforcement would have a measurable impact on injuries.

“I think it’s a really crude metric,” said David Ederer, a traffic safety researcher at Georgia Tech. “Let’s say you’ve got a lot of leaky pipes. Enforcement is like putting your thumb in one of those leaks, and then you take it off. You’re not actually patching it up.”

A weak relationship

In 2024, the SFPD issued 90% fewer traffic tickets than it did in 2014. But the number of annual traffic deaths has remained virtually flat since 2005.

Calculations using a number known as the correlation coefficient (opens in new tab) confirm that there is a weak relationship between numbers of deaths and traffic citations. Severe injuries show a stronger, but still moderate, relationship with citations.

This fact is more evident when the data is shown on a scatter plot. Each point on these plots represents one year. The bottom axis shows the number of severe injuries or deaths that year, and the left axis shows the number of traffic citations.

If there were a significant correlation between the two variables, the dots would form a rough line between the top left corner and the bottom right, or vice versa.

However, traffic citations include a broad category of violations — some of which, like expired tags, may have little effect on road safety. So city officials, including the grand jury, have directed the SFPD to home in on citations that are most likely to put people at risk.

These are known as “Focus on the Five” violations, which the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency says most commonly lead to collisions: speeding, violating pedestrian right of way, running red lights, running stop signs, and failing to yield while turning.

But Focus on the Five citations show an even weaker relationship with severe injuries, and further statistical analysis — using what’s known as a p-value (opens in new tab) — shows it’s likely that these same (or more extreme) figures would appear by chance, even if there were zero relationship between citations and deaths or severe injuries.

Rune Elvik, a lead researcher at Norway’s Institute of Transport Economics, analyzed San Francisco’s data and came to the same conclusion.

The analysis is not perfect. For instance, it doesn’t account for the multitude of other factors at play on the streets, or other efforts the city has made to abate crashes. But experts agree that the numbers show it’s dubious, at best, to directly link enforcement to deaths and injuries.

“It makes you question the argument that enforcement is the thing that’s needed,” said Julia Griswold, director of UC Berkeley’s Safe Transportation Research and Education Center. “The level of enforcement you’d need to have sustained effects is maybe not feasible.”

An SFPD spokesperson noted that the department has increased enforcement in recent years and said “keeping people alive and safe” is its top priority.

“We are using the personnel available to have the maximum impact,” the spokesperson wrote. “Our officers are identifying hot spots, collaborating with our city and community partners, making highly visible stops, and increasing citations.”

A new traffic safety philosophy

Traffic safety experts polled by The Standard said it’s possible for enforcement to make streets safer. The question, they say, is which measures are worth prioritizing in a city with limited resources and a low number of deaths per capita compared to other U.S. cities.

“If you were going to empower the SFPD to have 20 motorcycle units solely dedicated to traffic enforcement, and they were getting the red-light runners and DUIs and everything else, I suspect you would probably see a difference,” said James Davis, a professor of clinical surgery at UCSF Fresno who led a study of traffic enforcement in the Central Valley city. “But I don’t know that it’s fair to say that [the lack of progress] is the SFPD’s fault.”

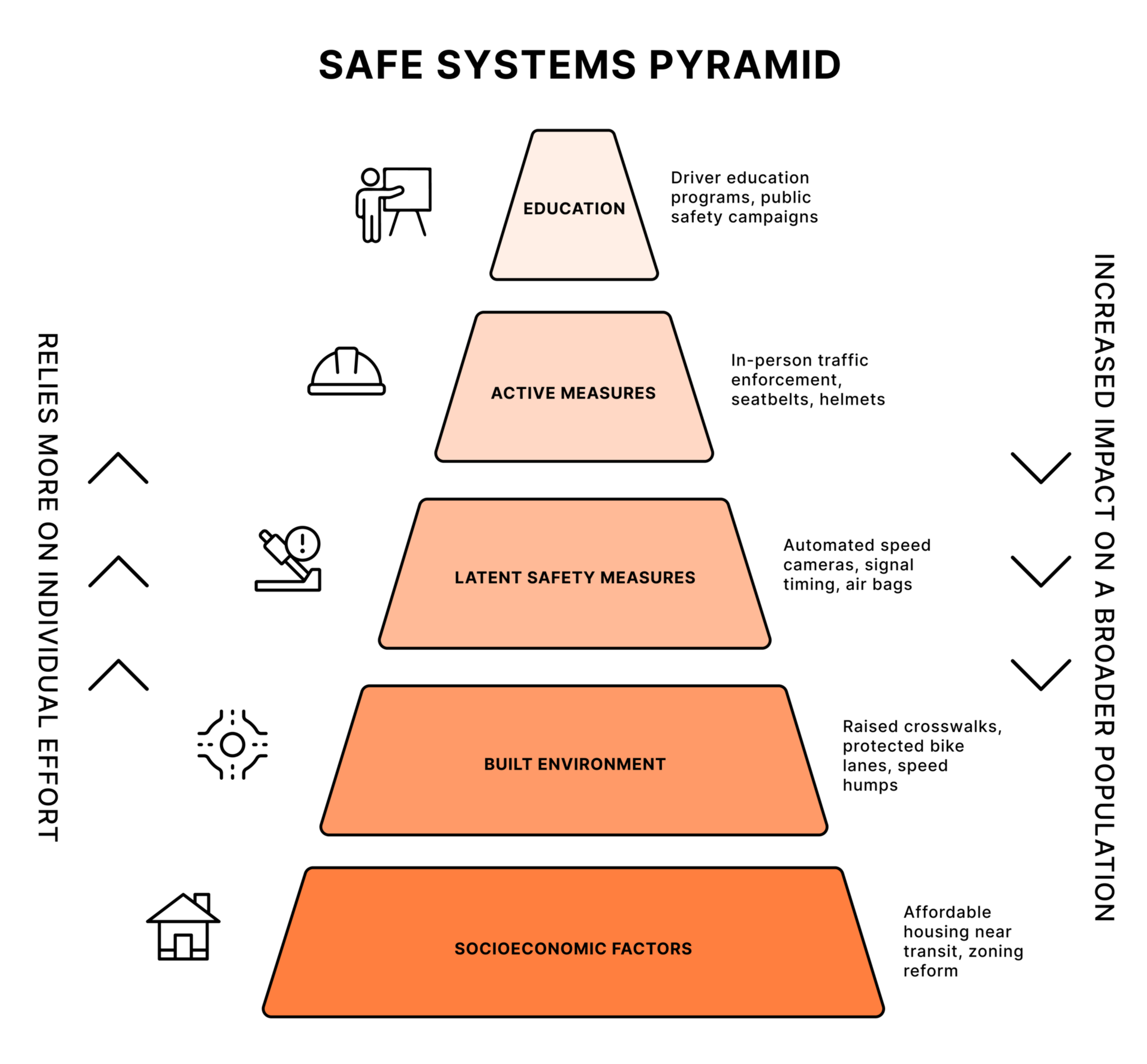

A new movement among researchers supports this idea. Known as the “safe systems pyramid,” it argues that officials should treat traffic deaths as a public health epidemic.

The philosophy is a notable divergence from the so-called Three E’s of street safety — engineering, enforcement, and education — that first gained popularity in 1923 and continue to dictate Vision Zero plans.

“Three E’s implies a false equivalency between the different factors and interventions,” Georgia Tech and UC Davis researchers argued in a 2023 paper (opens in new tab). “They often attribute outsize effectiveness to behavioral interventions and falsely assign blame to individuals in the roadway environment.”

Public health principles maintain that changes to systems, rather than a reliance on the choices of individuals, should be a priority. For instance, in a pandemic, issuing a stay-at-home order is more effective than relying on people to wear masks.

Under this framework, traffic enforcement by in-person police is one of the less effective measures to reduce deaths. It relies heavily on individual officers to fight the “pathologic agent” — kinetic energy — and has only a limited, sporadic effect on the broader population.

“In-person speeding enforcement is likely to target the fastest drivers, which is akin to only targeting the ‘sick’ individuals rather than the entire population,” the Georgia Tech and UC Davis researchers wrote.

Instead, installing traffic-calming measures like speed humps and raised crosswalks is more effective because it forces every driver to slow down. That doesn’t mean cities should stop enforcing traffic laws, nor does it mean increased enforcement can’t help; it suggests that cities should first divert resources to the most effective measures.

Ederer, the Georgia Tech researcher who was the lead author of the paper, said enforcement works best on “outlier behaviors” like speeding and drunk driving — “inexcusable” violations that police need to cite.

The problem is that many crashes occur when normal people make mistakes, Ederer said. That means the best solutions will force the entire population of drivers to change their behavior.

“We tend to moralize driving behavior, and I don’t think that’s correct,” Ederer said. “You should drive safely. But you can be doing everything right and still injure yourself and someone else in a crash. That’s how this system works, unfortunately.”

The safe systems pyramid argues that, despite posing massive political hurdles, changing street design and socioeconomic factors like how far people live from public transit are the most effective ways to reduce injuries.

“Instead of saying ‘Let’s try to make driving safer,’ how about we get people out of cars?” said Nick Ferenchack, who studies transportation systems at the University of New Mexico. “Get them walking, get them biking, get them on public transit. Not force them — but give them the option.”

Kate Blumberg, the grand jury’s investigation lead, said the group didn’t believe that police were “fully to blame” for San Francisco’s traffic deaths. She noted that the report considers the Three E’s.

“I don’t think you can ever say there’s one thing that’s going to make all the difference,” Blumberg said. “We see this as a three-legged stool. When you’ve taken off one of the legs, it’s not working.”

(In this analogy, she clarified, a toppled stool wouldn’t necessarily mean deaths and injuries would go up; only that they wouldn’t decrease.)

Indeed, the grand jury argued that while the SFMTA “has made real progress” in implementing street safety measures, it could be “more efficient and timely.”

“SFMTA shouldered much of the burden of Vision Zero, and clearly feels the weight of that responsibility,” the report says.

The report suggested that the SFMTA develop a street safety education campaign that focuses “on ways all road users can prevent the traffic violations that result in the most severe and fatal injuries.”

“We’re not saying it’s all the police,” Blumberg said. “But these things go together, and I do think it’s fair to say the reduction in citations does increase risk.”

Looking ahead

San Francisco may not have hit zero traffic deaths by 2024, but experts say they have hope for progress. That’s partially because of one promising development that has come to the city: automated speed cameras.

The 33-camera system started issuing warnings to drivers in March, but fines don’t start until Aug. 5. It’ll take more time to learn how effective they are. Under the “safe systems pyramid” framework, though, they’re considered more effective than in-person police enforcement: Cameras theoretically encourage all drivers at all times to slow down.

Most cameras are issuing 100 to 200 violations per day, SFMTA officials say. Some locations — like Geneva Avenue between Brookdale Avenue and Prague Street — are racking up as many as 1,779 violations per day, according to ABC7 (opens in new tab), although Ederer said that in other cities, automated citations tend to fall after an initial spike.

SFMTA officials, for their part, have argued (opens in new tab) that Vision Zero helped direct attention to traffic safety. That will become increasingly important as advocates push (opens in new tab) Mayor Daniel Lurie to adopt a new policy after the original one expired last year.

When asked whether Lurie plans to readopt a Vision Zero plan, a spokesperson pointed to remarks the mayor previously made where he lauded speed cameras and said, “We are going to keep doing whatever it takes to keep our residents and visitors safe.”

Meanwhile, the SFMTA temporarily suspended (opens in new tab) a program in June that allowed residents to request traffic calming measures in their neighborhoods, saying it was flooded with more requests than it could handle. The agency delayed plans to fully enforce the state’s new daylighting law until next year.

“We’re going through a paradigm shift where we’re understanding traffic crashes in a new way,” Ederer said. “We’re looking bigger at what might be causing these crashes. We’ve been a little reductive for a couple decades.”