Lee Datrice has been on the road since selling his Fresno ranch six years ago. He could live with his daughter in Oakland, but he prefers an RV parked in San Francisco.

“All my kids are grown. All my grandkids are grown,” said Datrice, 72. “I just like being free.”

So he was perturbed to hear about Mayor Daniel Lurie’s plan to get RVs off the streets and offer housing vouchers to those living in them.

“What kind of housing is it? Living with a bunch of crack addicts or something?” Datrice asked.

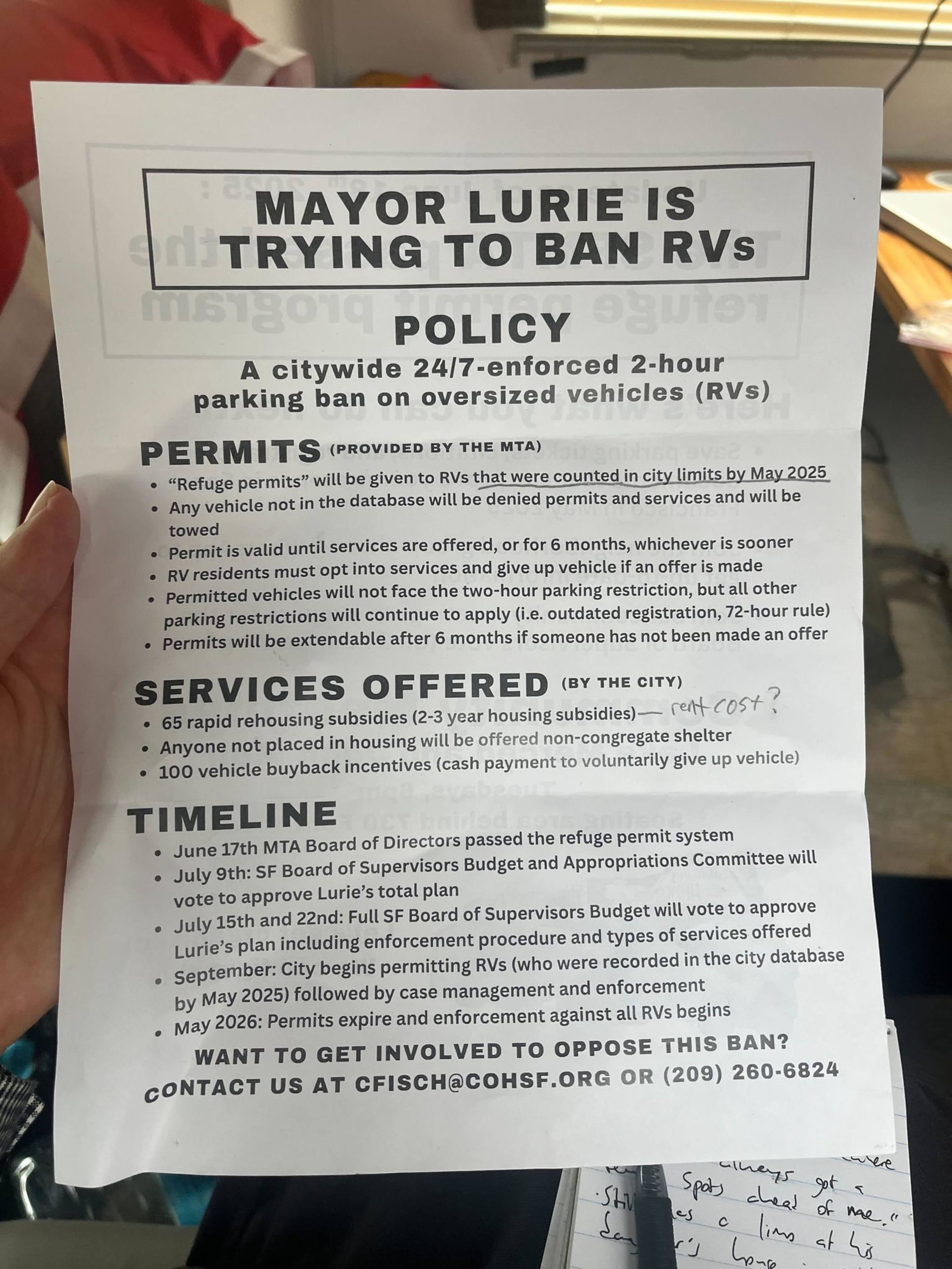

Lurie’s legislation (opens in new tab), introduced last month, would make it illegal to park large vehicles on city streets for more than two hours. The bill passed the Budget and Finance Committee on Wednesday and is expected to pass the full Board of Supervisors in September. If so, the city will begin distributing “refuge permits,” allowing RVs that have been here since May or earlier to avoid being towed for up to a year. Permit holders would be offered housing vouchers or cash to give up their vehicles.

The incentives will include housing subsidies — money for rent — for two to three years, or private rooms in a shelter.

But whether or not residents accept those incentives, city workers would begin towing non-permitted RVs in mid-October. By next fall, all refuge permits would expire, barring special intervention by city officials, and RVs will be fair game for towing even if their residents have not received a housing offer.

Datrice said he would rather pay a modest amount — say, $300 per month — to live in a legal RV park with sewer and water hookups. A safe RV site that operated for three years at Candlestick Point shut down in April amid persistent complaints from neighbors.

Many RV dwellers are not there by choice. Devin Plant scrapes by tutoring SF State students in data analytics, he said, and has a job canvassing against the recall of Supervisor Joel Engardio. But it’s not enough to live on, and he’s flat broke. He said a city crackdown is the last thing he needs.

“It’s further displacement, harsher conditions, pushing the most disadvantaged further into the crevices,” Plant said, adding that he’d rather get a voucher for repairs at a mechanic’s shop. “It’s funny they want to give me a voucher to, what, discount the money I’d pay to a landlord? I can’t afford to pay a landlord, even with a discount. That’s why I’m here.”

He shared a flyer he’d found on his windshield with information about Lurie’s bill and a Coalition on Homelessness email address. “Let’s get organized!” the flyer says. “We can fight this!”

When the crackdown comes, Plant will likely just park outside city limits, even though he’d rather stay local, he said. Originally from Florida, Plant has stayed in San Francisco — “one of the coolest places to live” — on and off for a decade.

Kunal Modi, Lurie’s homelessness chief, told supervisors at a committee meeting Wednesday that the city owes RV residents compassion, but the public deserves “safe and clean public spaces,” KQED reported (opens in new tab).

Coalition on Homelessness organizer Lukas Illa, who has been involved in recent outreach efforts through the End Poverty Tows Coalition (opens in new tab), learned of Lurie’s plan in May.

“When the city has an issue with parking on a major corridor, they talk to the business owners, and they talk to the housed residents,” Illa said. “But nobody ever engages someone living in an RV.”

Illa said the plan was designed to appease residents who don’t want to see RVs in their neighborhoods, not to help those living in the vehicles, adding that the city does not have enough housing vouchers, shelter beds, or administrative capacity to accommodate all vehicular residents.

“None of this follows the public health guidance (opens in new tab) that has come out about vehicular homelessness,” Illa said. “None of it says, ‘Yup, further criminalization.’”

A spokesperson for the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing said the city had enough resources to accommodate families living in vehicles, but did not mention single adults.

Anthony Feranchek, 39, said he has lived in his RV for about a year and works as a caregiver for an elderly disabled man. When he’s not doing that, Feranchek drives for Lyft in his Tesla Model S, which he parks next to his RV. But he still doesn’t earn enough to rent an apartment.

A few months ago, city workers told him about a program through which he could get a tiny home if he gave up his RV, he said. He was interested but ended up not qualifying.

“Most people in RVs are willing to compromise,” he said, “if it’s a good compromise.”

Feranchek, who has two dogs, is worried about his and his pets’ safety if they were to move to a shelter.

“That’s a step down for people in campers,” he said. “We want them to work with us.”