Few understand the complications of genius better than Walter Isaacson.

The journalist and biographer has trailed Elon Musk across a Tesla factory floor. He listened to Steve Jobs retell his whirlwind life story in the weeks before his death. He chased Leonardo da Vinci and Benjamin Franklin back through the centuries, from their public triumphs to their most intimate notebook entries.

He has asked sweeping questions about what makes visionaries and technocrats click: how they manage to see what we miss, and where they want to take humanity next.

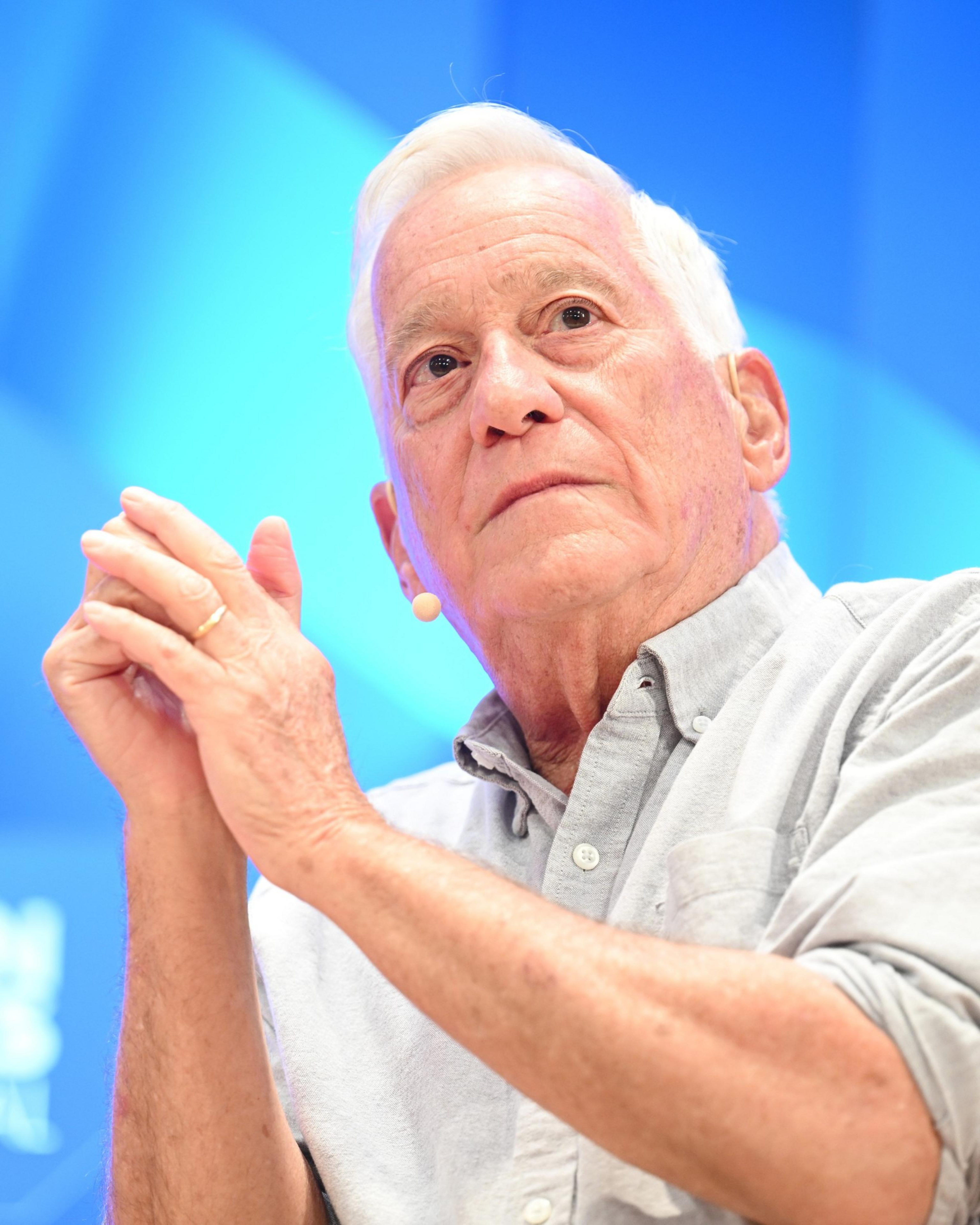

In The Standard’s “Life in Seven Songs” live show last month at the 2025 Aspen Ideas Festival, Isaacson, a former editor of Time and president of the Aspen Institute, sat down with host Sophie Bearman to tell his own story: what drives the biographer behind our most polarizing geniuses.

‘Money-making engine’

It was 1967. Inside the bustling Preservation Hall at the heart of New Orleans’ French Quarter, Sweet Emma Barrett was all the rage.

Most nights, 15-year-old Isaacson wove between the benches to the front row. Onstage was Sweet Emma, a fiery 70-year-old New Orleans institution whose entire frame seemed to bounce as her hands capered across the keyboard. He curled up on the floor, practically at her feet.

How actress Pepi Sonuga keeps the faith — even when Hollywood says, ‘We don’t need you’

Before becoming a drag icon, Peppermint found inspiration in Prince

Before Sam Sanders became an American culture guru, pop music was ‘forbidden fruit’

“She wasn’t all that sweet,” Isaacson quipped six decades later, his wrinkles blooming into a smile. He remembered the Preservation Hall crowd tossing dollar bills into a hat late into the night, keeping the song requests flowing alongside the applause. One request — at $5, 500% the price of a usual ask — always topped the list: “When the Saints Go Marching In.”

“They made it a money-making engine,” Isaacson said. It’s only fitting that he’s made a career shadowing Silicon Valley wizards spinning up money-making engines of their own.

‘Those demons that still may be lurking’

Jobs was gravely ill. Isaacson was beside him, writing the story of his life.

Away from the public eye and fortune-telling about the products that would shape our future, the tech titan had turned to music as his way to hold on. “All his songs. He played them over and over when he was dying,” Isaacson remembered.

Isaacson asked most of the questions across their scores of interviews, but Jobs had one of his own as he lay dying. “If the building catches on fire — and you can save only one set of originals — would you save: the Beatles or the Stones or Dylan?”

Jobs’ own answer was clear. “My model of business is the Beatles,” he had told (opens in new tab) “60 Minutes” in 2003. At the launch of the iPhone, he played (opens in new tab) “Lovely Rita” as the crowd erupted in applause. But if Isaacson could get behind Jobs’ genius, he was slower to get behind Jobs’ taste.

“I ended up being a Stones person,” Isaacson remembered. In college, he had fallen in love with “Sympathy for the Devil.”

“I write about really creative people, and one thing they have in common is they’re all misfits,” Isaacson said. Leonardo, illegitimate, left-handed, gay. Einstein, Jewish in Germany. Jobs, abandoned at birth. “Sympathy for the Devil” held a microphone to “those demons that still may be lurking in all of us,” Isaacson said.

‘We would come back’

When Hurricane Katrina tore through New Orleans in 2005, the levees failed. So did Isaacson’s faith. “We thought the city wasn’t coming back.”

“We had to make a deal with the good lord,” he recalled. More than 1.2 million residents had fled the city. But one thing could not go for good. “Jazz Fest has to come back.”

In 2006, it did. At sundown, as hundreds of thousands of outstretched hands cupped the fading light, Bruce Springsteen roared (opens in new tab) into “My City of Ruins.”

“Everybody’s singing, ‘Rise up.’” Nearly two decades later, Isaacson’s retelling tapered to a whisper. His voice quivered.

Springsteen had growled the “rise” with a bellow, as if carrying an entire city’s resolve in a single syllable.

“I’m choking up here,” Isaacson gulped, pressing his hands to his lips. “Imagine 20,000 people singing that. I knew it: We would come back.”

‘The magic words’

On the gilded Aspen campus, where conversations zip across well-manicured lawns like hummingbirds, Isaacson paused to scratch his head.

“Geniuses? Part of it is the cradle of creativity that allows that genius,” he concluded.

In 2018, after a life ricocheting around the world, he decided to return to his: the city that raised him. Today, Isaacson teaches at Tulane University. His office sits within a five-mile radius of Preservation Hall and Springsteen’s stage at the 2006 Jazz Festival.

“Cradles of creativity. That’s what’ll bring America out of its current crisis,” he said.

So it all came back to New Orleans. “This place is rich with idiosyncrasies and struggle and all the things you look for in a character,” Bearman said. “It shaped him.”

If Isaacson’s New Orleans was magical, he now carries a piece of it with him. He can channel it on command.

“The magic words are: Let me tell you a story.”

Listen to the full episode here (opens in new tab). Find Isaacson’s playlist on Spotify (opens in new tab) and transcript (opens in new tab) on our website. Email us at [email protected].