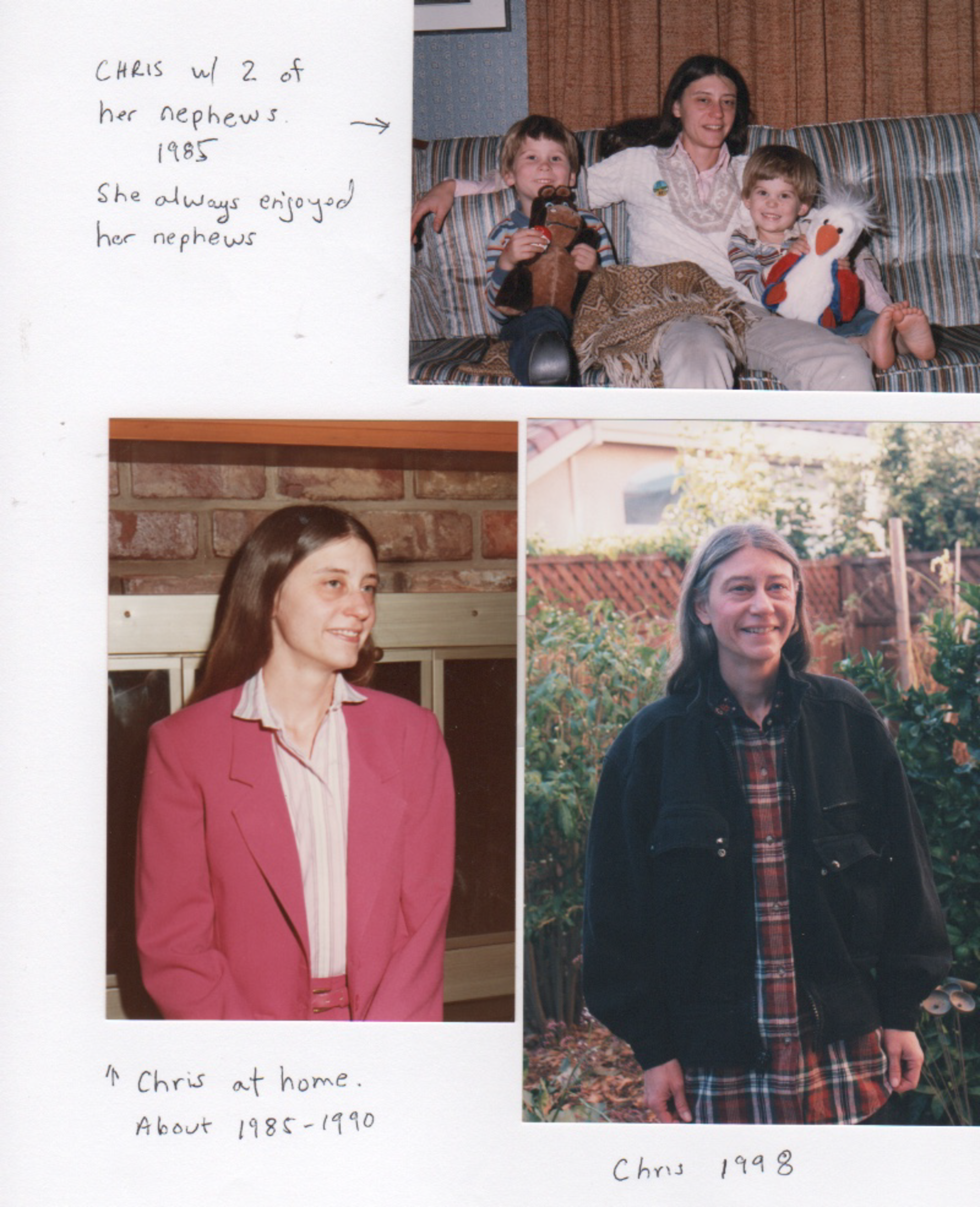

Chris Moyer never felt quite at ease growing up in the flatlands of Oklahoma City. Slender, with straight brown hair and a subtle, wan smile, she read books with near obsession, immersing herself in stories of elsewhere.

Like many before her, she was drawn to the idea of San Francisco and moved west in the early 1980s to chase a Summer of Love that had ended more than a decade prior. Over the next 30 years, she made a life for herself, settling into the Rose Hotel in SoMa where she had a community of friends and proudly expressed her fierce loyalty to her adopted home.

That life came to an abrupt end in a back alley on Christmas Eve in 2018 (opens in new tab). Michael Jacobs — four days out from a state-run mental hospital — allegedly snuck up behind the 64-year-old Moyer as she was smoking, stabbed her in the back, and slashed and sawed at her throat with a butcher knife, nearly decapitating her.

Before approaching Moyer, Jacobs, who was 27 at the time, removed his shoes and tossed his hood over his head, according to video footage. After she fell into his arms, then flopped to the ground, he wiped the blade on his pants and walked away, leaving a trail of bloody footprints, court records allege. He then calmly put his shoes back on and left the scene.

She bled out within seconds, according to her brother Robert Moyer.

“It was a very brutal attack,” he said. “You wouldn’t want to encounter this guy or have him encounter you and decide you are some kind of target. You wouldn’t stand a chance.”

Just six hours after allegedly killing Moyer, Jacobs struck again outside Third Street’s California Pizza Kitchen, allegedly lacerating Maritza Mercado’s throat while she sat at a table, according to court documents. She barely survived.

Jacobs was arrested Dec. 25, 2018, a few blocks away. His boots, face, and clothes were covered in blood. A knife was stashed in his jacket. Authorities moved quickly, charging him in January 2019 with murder and attempted murder. Jacobs pleaded not guilty despite the strong evidence police had collected, including video of the killer matching Jacobs’ description, a witness identifying him in the second attack, and DNA on the knife and his sock matching that of both victims.

But six years later, the case remains in limbo as Jacobs is unable to stand trial because courts have ruled that he lacks mental competency. By law, he can’t be kept in jail for a crime of which he has not been convicted. But he also can’t be sent to the overcrowded Napa State Hospital, whose doctors tried but failed to improve his condition so that he could stand trial.

Instead, despite serious warnings from doctors and prosecutors, Jacobs has been stashed in the only place the law allows: the privately run Crestwood treatment center on the fifth floor of UCSF Health St. Mary’s hospital. Located next to Golden Gate Park, near the bustling corner of Haight and Stanyan streets, Crestwood has a long history of patients going missing. In the past three years, in fact, at least 20 patients were reported missing by staff, according to 911 dispatch records.

Jacobs’ story is an extreme example of how California’s byzantine and overstrained mental health system intersects with a criminal justice process that doesn’t always kick in until it’s too late. Having cycled in and out of mental institutions for years, Jacobs personifies the state’s complex conservatorship process, illustrating the limits of what can be done legally to protect the public from someone who remains dangerously sick.

“This defendant is homicidal,” Assistant District Attorney Sean Connolly wrote this spring in a filing requesting a more thorough review of the threat Jacobs poses to society before his transfer to Crestwood. “The last time he was released, he murdered one person and tried to murder another.”

Revolving door

It’s impossible to know what drove Jacobs to allegedly kill Moyer. Much of his mental health history is locked away in confidential files. However, some of his life since 2018 can be tracked through public documents. What they show is a fragmented mental health system that cycles patients in and out of crowded and overtaxed institutions and passes responsibility from one authority to another.

Jacobs’ recent spell of institutionalization began in spring 2018, after he was arrested and charged with burglary in Merced County. A judge ruled him mentally incompetent, and Jacobs was sent to Napa State Hospital, one of six facilities in California that handles cases of mentally ill people facing criminal charges. A few months later, after being deemed competent to stand trial by the hospital’s doctors, he was returned to Merced County.

He pleaded no contest to burglary charges and was sentenced to time served. A week later, he was sent to another county jail, this time in San Mateo County, on a warrant for failing to appear in court for a petty theft case. He pleaded guilty, was again sentenced to time served, and was released Dec. 20.

Less than five days later, he was in San Francisco, allegedly killing Moyers and attempting to kill a second person.

With Jacobs behind bars on the murder charge, the pattern began anew. For the next six years, he cycled in and out of San Francisco County Jail and state mental hospitals, with little improvement and continued debate on whether he could be in front of a jury. In one instance, the state hospital declared him fit to stand trial in March 2023, only to have a judge express doubts about his competency three months later.

“He has been in this revolving door,” Moyer said. “They will get him back on his feet, where he at least can be released from the facility, presumably to stand trial. He goes back to the county jail, where he deteriorates psychologically, and then he ends up back in the hospital.”

One of the sole resources for people like Jacobs, who face grave criminal charges yet cannot care for themselves because of mental health issues, is involuntary conservatorship, wherein they are placed in privately run mental health facilities like Crestwood.

Since the dismantling of the state mental health system in the late 1960s under then-Gov. Ronald Reagan, California counties have taken charge of most mentally ill people in crisis.

“He can’t stand trial, and you can’t lock him up forever for a crime he has not been convicted of,” said former San Francisco public defender Kara Ka Wah Chien, who specialized in such cases but did not represent Jacobs.

By early 2025, authorities decided to put Jacobs in an involuntary one-year conservatorship, which allows the county, through the Public Conservator, to have legal power over where he would live and the kind of treatment he would receive. The aim was to bring him back to a competent level to face trial, or remain in some kind of care indefinitely.

Such conservatorships don’t have a great track record of success. More than half of all conserved people fall back into the criminal justice system because of mental health crises, according to a 2020 state audit (opens in new tab).

In response to the audit, San Francisco public health officials admitted that the city is “struggling with the severity of needs of our residents who have mental illness, particularly when this is impacted by the effects of psychoactive substances, complex trauma, homelessness [and] racial oppression.”

Officials laid the blame, in part, on a lack of beds in state mental hospitals to deal with the most severe and violent cases. The shortage has had a direct negative impact on San Francisco, where, as of April, there were 700 people under conservatorship, among the highest number per capita of the 12 large California counties reviewed in a 2022 report (opens in new tab).

In 2022, former prosecutor Michael Menesini and others warned that the city attorney’s office should not handle conservatorship cases due to its focus on civil rather than criminal cases. Those concerns were overridden.

“It’s only a matter of time before the dam breaks,” Santa Clara Deputy District Attorney Brandon Cabrera said of the rise in conservatorships in his county. “Capacity, bed space, and appropriate facilities and supervision to manage this population have become challenging for all.”

A secure healing center

Few would disagree that Jacobs should be in a secure facility where he can get treatment without risking harm to himself or others. At first blush, Crestwood seems to fit the bill.

In court for a hearing on Jacobs’ transfer, Deputy City Attorney Kimiko Burton described 54-bed Crestwood (opens in new tab) as “a private, secure facility. This is a locked facility.”

But despite these assurances, the center has a spotty history of keeping patients inside its walls. In the past three years, at least 20 have gone missing, according to 911 call records. In 2022, a 35-year-old man “ran away.” The next year, a “client awol’d,” and in 2024, a patient went missing after an outing in Golden Gate Park. In one of the five reports made this year, a patient went AWOL while a staffer escorted them to the Social Security office. Crestwood reported its most recent missing person in April.

In a statement sent after this story's publication, a Crestwood representative acknowledged that 23 patients had left without authorization in recent years and that "approximately 40% of these same individuals returned to the facility" after police were called.

A social worker who had several clients escape from Crestwood over the past six years said the facility is neither secure nor a place where many people recover. When her clients did depart the facility without authorization, she was not made aware by Crestwood.

“I think that someone like [Jacobs] … needs to be in an actually well-staffed, locked facility, and Crestwood is just not competent,” said the social worker, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of professional reprisals. “If these facilities actually were what they purport to be, which is a secure psychological facility, it would be another story.”

When a reporter from The Standard visited the hospital April 4, he easily made it to the fifth floor by following a nurse who used a secure key-card to access the facility via an elevator. The reporter wasn’t asked for security credentials nor stopped when he entered a day room with a view of Golden Gate Park. In an adjacent room, a man who appeared to be a staffer sat chatting with a woman. On a far wall, a hand-written poster congratulated the staff for an “AMAZING state survey!!!” After milling around for a few minutes without being questioned, the reporter departed.

“It’s not secure,” said Kelly Kruger, a recently retired SFPD police officer who has experience working with the facility. “If someone was halfway plotful, they are gonna be able to leave.”

UCSF Health referred questions to Crestwood. The city attorney’s office said in a statement that Crestwood is secure, but the office could not speak on the details of Jacobs’ case other than that it followed the law.

The state’s licensing agency, the Department of Healthcare Services, said in a statement that the facility was issued citations in its most recent review but would not provide those citations or comment on whether it was aware of patients missing from Crestwood.

In its statement, a Crestwood official said it could not comment on the Jacobs case, but is conducting a review of visiting protocols in light of The Standard reporter accessing the facility's lobby.

The official explained further that "a locked psychiatric facility is not a prison, and residents do not 'escape' in the same way one might think of a correctional facility. A key part of the recovery process is gradually reintegrating residents into the community as a first step toward rebuilding productive lives."

‘Currently dangerous’

The fight over Jacobs’ future has pitted city officials against one another as they litigate in mental health courts the public threat he may pose.

There are two kinds of involuntary conservatorships related to severe mental health issues: Lanterman-Petris-Short, or LPS, and Murphy. LPS conservatorship is for people who can’t care for themselves but are not a danger to others, while Murphy is for the small group who may be seriously violent. While both can result in involuntary locked housing, any change to housing or treatment in a Murphy conservatorship must be approved by a judge, adding an additional safeguard.

Jacobs was initially put in the less-restrictive LPS conservatorship because a doctor deemed he did not pose a safety risk. But the DA’s office asked the judge to seek another assessment, arguing that Jacobs remains dangerous and should be transferred to a facility with the highest level of security. Prosecutors cited recent reports of Jacobs’ behavior in the county jail, where he wasn’t cooperating with mental health services and often refused his medication, leading staff to sneak the drugs into his food.

An Oct. 20, 2024, evaluation noted that he “continues to present as a danger if his symptoms are left untreated” and “would pose a risk to the community” if released, according to court documents. On Nov. 1, a doctor wrote that Jacobs needs a locked treatment facility because of his “severe symptoms” and “assaultive behavior.”

The city attorney, who represented Jacobs via the Public Conservator, countered that a consulting doctor found him not dangerous and that he’d be sent to Crestwood regardless. A judge ruled in favor of the city attorney’s office and against a second medical opinion.

Jacobs’ criminal defense attorney, Peter Fitzpatrick, contends that his client needs treatment and that he will never be allowed back on the street. “There’s no issue about what’s going to happen to this guy. This guy’s going to be in a locked facility no matter what.”

Despite such reassurances, Fitzpatrick acknowledged that the system is less than perfect. “It’s obvious that the system doesn’t accommodate people with serious mental health issues,” he said.

In a year, when Jacobs has his annual conservatorship reassessed, the Public Conservator responsible for his care has the power to change his medication or move him to a less secure facility without going before a judge.

For Chris Moyer’s brother, the potential of Jacobs escaping or being released to a less secure facility is harrowing.

“She does not have a voice other than this. She was brutally murdered,” he said. “Everybody should be concerned about this guy falling through the cracks.”

This story has been updated with additional comment from Crestwood.