Welcome to The Looker, a column about design and style from San Francisco Standard editor-at-large Erin Feher.

When Brett Terpeluk arrived in San Francisco, he didn’t start small. The young architect was sent to the city in 2004 to lead the design and construction of the avant garde renovation of the California Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park.

“It was sort of a very expensive science experiment, but it worked, ”said Terpeluk, whose boss, the famed Italian architect Renzo Piano, had shipped Terpeluk over to the States as his emissary. Once here — and once the beast of that initial high-profile project was wrapped four years later — Terpeluk settled into his own architectural practice, often collaborating with his wife, the landscape designer Monica Viarengo, whom he had met during his decade-long stint in Genoa, Italy.

Fifteen years later, it was Viarengo who brought Terpeluk onto another quintessentially San Francisco project — one with a rich local history and some thorny design challenges. A couple had purchased a 1970s time capsule of a house in Noe Valley designed by Albert Lanier, the husband of Ruth Asawa. They had hired Viarengo to design the landscape, but the structure itself was proving harder to pair with an architect.

Clocking in at just 1,800 square feet, the house wowed at first glance — the main space was all provocative angles and skylights that created an ever-shifting gallery of sunlight and shadows. A wall of windows framed a triple-threat of a view: the downtown skyline, the signature Twin Peaks stacked with houses, and the bay beyond. But the property was showing its age: The kitchen and baths were dreary and dated and the exterior shingles and rafters were rotting from years of exposure to the fog that tumbled down over the hill each afternoon. An overlayering of dark interior wood — redwood, pine, cedar, and oak — was aesthetically stifling, especially in the warren of rooms on the lower levels, where the ceilings dropped and the windows were sparse.

By the time Viarengo recommended her husband for the job, the homeowners had already dismissed two previous architects, whom they described as wanting to leave too much of their own mark on the property. They were looking for a lighter touch — someone who would honor the property’s existing DNA.

Terpeluk immediately hit it off with the owners. Like them, he felt a mix of awe and protectiveness when he first visited the home. “It was clear to me immediately: We really need to be careful with this house,” Terpeluk recalled. “To not cannibalize what’s here or alter that incredible feeling you have when you walk through the front door.”

That feeling could be credited to Lanier, who designed a handful of houses in Noe Valley, including one nearby that he shared with Asawa and their six children. That home’s iconic living room was recreated inside SFMOMA as part of the museum’s current Ruth Asawa retrospective (on view until Sept. 2). Lanier died in 2008, just three years before this house landed on the market. It was listed just north of a million dollars, and more than 20 offers stacked up quickly. Terpeluk is grateful his clients came out on top. “They were totally committed to this old house, and to taking care of it,” he said.

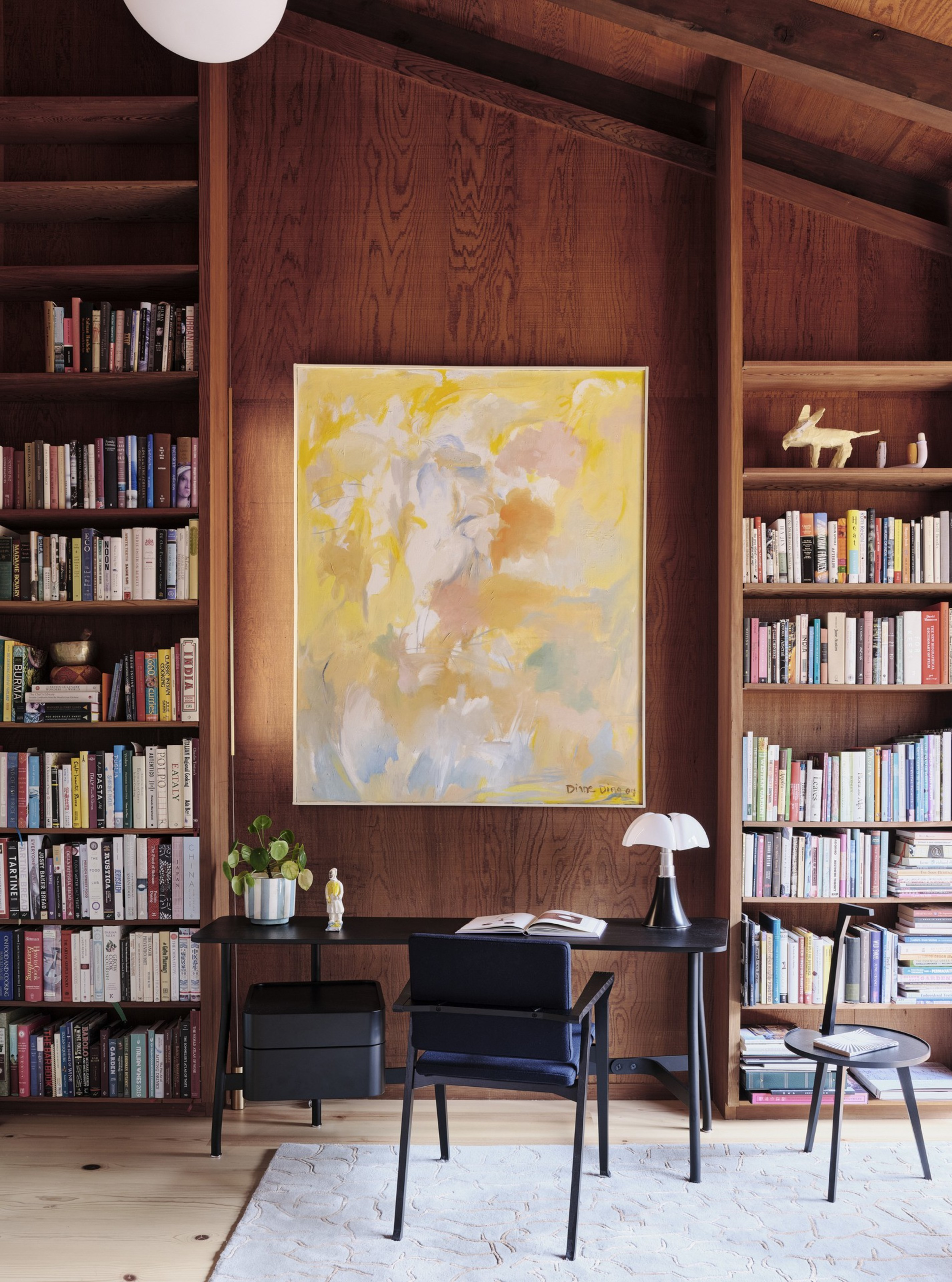

The design and construction process took about four years, during which Terpeluk acted as a surgeon, gingerly removing large wall panels of rough-sawn redwood — nearly impossible to source today — restoring them, and reinstalling them. “The client and I really felt connected to this material, even though it darkened the space,” said Terpeluk. “It created this cocoon-like environment.”

While the team was committed to keeping many existing elements, they were also eager to reimagine others. The original single-pane windows were all replaced with modernized versions, and the dark oak floors were swapped for lighter douglas fir planks freckled with tight black knots. Terpeluk chose the material both for its history — they were rescued pier pilings from Treasure Island — and the way the black knots echo the new blacked steel railings lining the open tread stairs now connecting the home’s three levels.

But the most eye-popping update is the collection of high-gloss kitchen cabinetry in perky pastels, the shade and shine reminiscent of a sweet handful of Jordan almonds candy.

“The rough-sawn redwood had such a strong presence, I thought it would be really nice to have something with a sharp contrast or high gloss to play off of it,” Terpeluk said. The architect knew that bringing bold colors into the sacrosanct space was a high-risk move, so he called in an expert. Color consultant Beatrice Santiccioli was a friend and fellow Italian transplant with an instinct for picking perfect palettes — during her time with Apple she curated the collect-them-all colors for the iconic iPod Nano.

“She just lives in this chromatic world, and she has such a deep understanding of color,” said Terpelek, who admits the combination of pink, minty green, and yellow that coats the kitchen would have never occurred to him. Even with the daring infusion of contemporary color, the main floor retained its spirit of 1970s Northern California, a womb of unfinished wood and slices of sky.

The bottom two floors, carved into the hillside, received a more dramatic revamp. Terpeluk chose to rid them of the heavy wood treatment altogether, and added additional square footage (and higher ceilings) by excavating beneath the house and taking over dead space beneath an old deck. Where the lower two levels once felt like an awkward architectural afterthought, they now possess the same signature connection to the outdoors as the showstopping main floor.

Santiccioli sprinkled her prismatic fairy dust throughout the downstairs, too, coating an indoor-outdoor kitchenette in foggy blue and adding a splash of deep crimson to a new bath. The colors harmonized with the flowers, fog, and sky just outside. Each floor opens to its own thoughtfully landscaped green space designed by Viarengo. One imagines that Lanier, a passionate gardener who was often clad in farmer’s overalls, would be proud of the house’s evolution.

“There are times as an architect to be really bold and aggressive stylistically with interventions,” Terpeluk said. “And then there are times where you really have to step back and understand what kind of dialog you want to have with the history and the DNA of the structure. This house is almost like a living, breathing organism. And we wanted to keep it alive.”