Every time Gary McCoy applies for a job, he discloses his extensive criminal record. And with that declaration comes the familiar anxiety over what his prospective employers will find.

Grand larceny. Felony theft. Probation violations. Failure to appear in court. Driving on a suspended license. Drug charges.

McCoy’s record has shadowed him throughout his life, even as he got clean and found work that propelled him to the top of San Francisco’s political hierarchy.

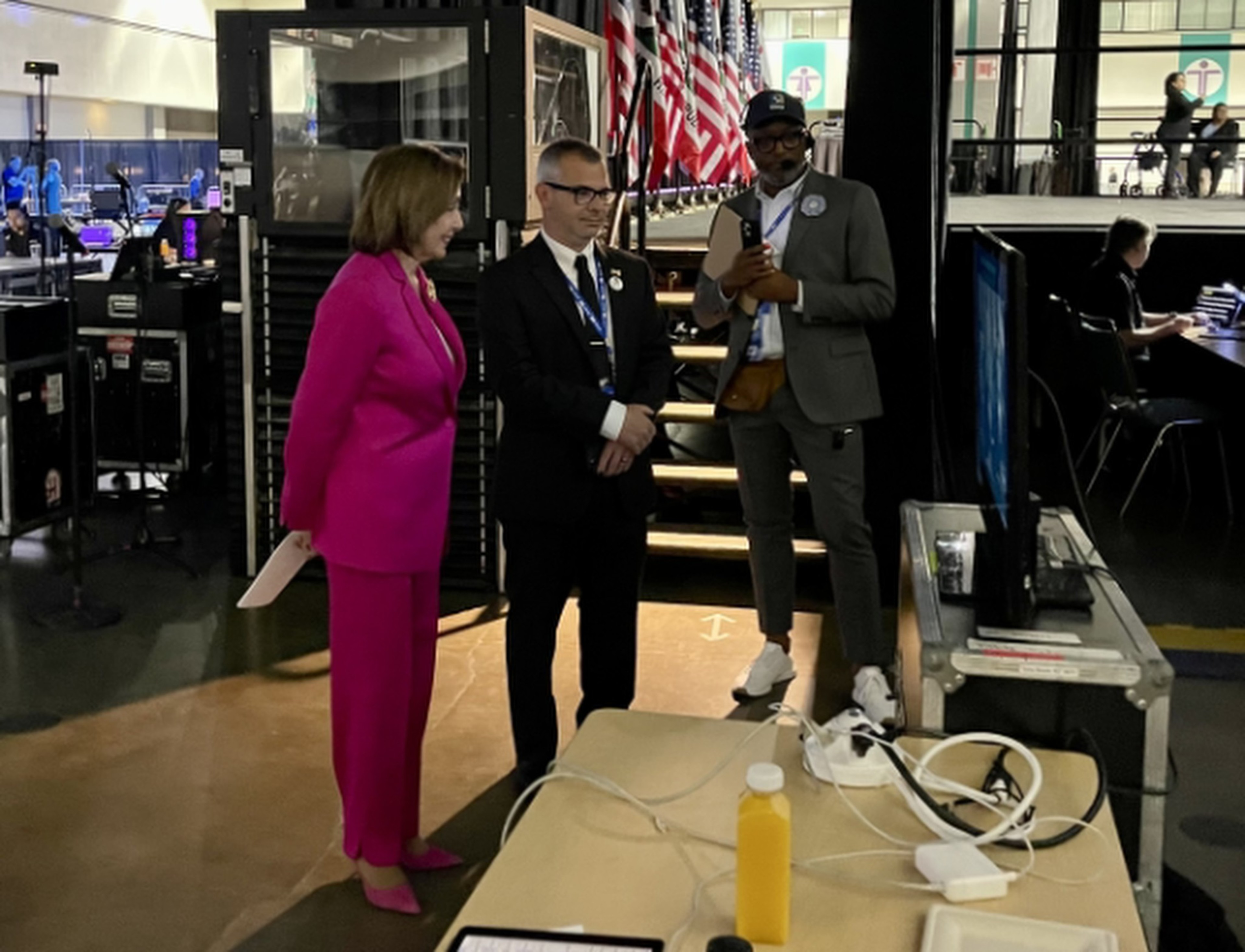

It haunted him in 2011, when he was hired as a legislative aide in then-Supervisor Scott Wiener’s office. It resurfaced in 2014, when he joined then-Supervisor London Breed’s team, then three years later, when he became a congressional aide to Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi.

Now, McCoy, 47, is disclosing his criminal past as part of his most consequential job application yet: his campaign for District 8 supervisor.

Nearly 15 years after McCoy first ventured into politics, he filed paperwork this week to run for supervisor, with plans to formally launch his campaign at an event on Saturday.

He is sharing his partially expunged criminal record exclusively with The Standard to demonstrate transparency and so voters can see how far he’s come. He also wants the 85,000 constituents of D8, which includes the Castro, Noe Valley, and part of the Mission, to see how his experiences make him uniquely qualified to tackle San Francisco’s housing crisis, drug use, homelessness, and crime as their supervisor.

“I wouldn’t be passionate about the things that I’m passionate about today if it weren’t for that,” McCoy said during a recent hours-long interview on the back patio of the Castro Country Club. “And I wouldn’t have the outlook and the perspective on things that I have today.”

‘I wanted to die’

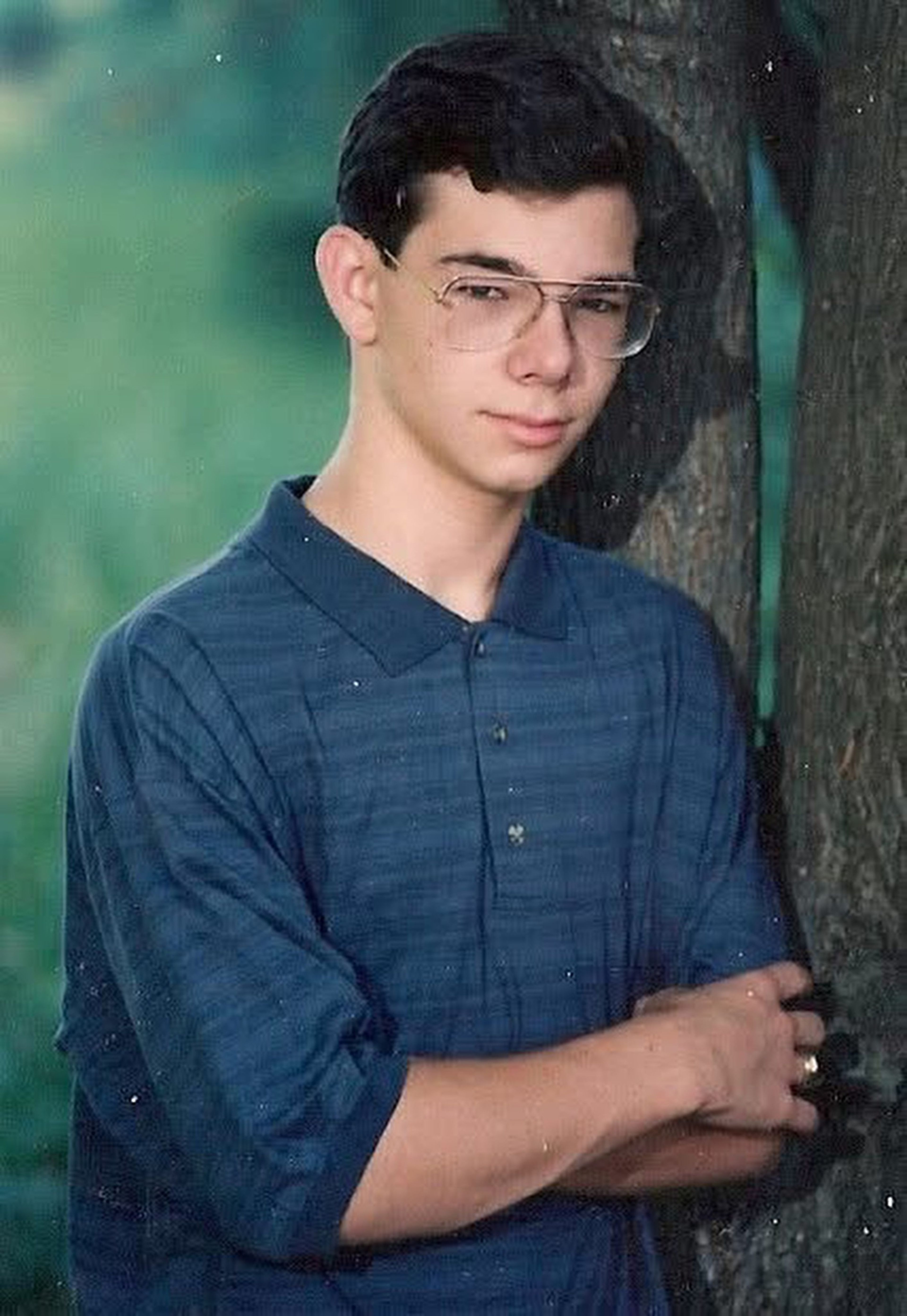

McCoy’s criminal behavior began in 2000 in his hometown of Norfolk, Virginia, and spanned a decade that included a move to San Francisco around 2002.

It started when McCoy was better known as Sharky, a 20-year-old punk with a gleaming silver mohawk who booked bands at venues across northern Virginia. Between sets of the ska-like brass horns of Buck-O-Nine and the thrashing guitars of the Voodoo Glow Skulls, Sharky would sneak to a bathroom and snort meth off a key.

What had started as teen drinking evolved into a hard-drug habit that helped him tune out memories of his father’s physical abuse and alcoholism and the fights between his parents, who ultimately divorced.

McCoy, who is gay, lived with a woman he called his drug “partner,” injecting heroin with her in an apartment adorned with little besides air mattresses and needles. They financed their habit with petty theft, stealing small items from one Walgreens location and returning them at another for cash. They elevated that grift one day with a trip to Walmart, where they were caught trying to steal a computer. McCoy was charged with grand larceny.

That crime stands out as one of the most serious charges on his rap sheet, which also includes drug offenses and misdemeanors. In 2000, he served roughly nine months in a Chesapeake, Virginia, jail for probation violation in the wake of the grand larceny arrest.

The court drug-tested him at each probation check-in, and he tested positive for heroin each time. Eventually, he stopped going.

In 2002, McCoy sought a fresh start in San Francisco, telling his family he could get sober. He made it barely a month before he was arrested on 16th and Mission for possessing and attempting to distribute heroin.

McCoy spent a weekend in jail and was bailed out on a $10,000 bond. He quit his job as a promoter for a radio station, started using meth again, lost his home, was sentenced to drug court, and learned that he and his then-boyfriend were HIV positive.

“I wanted to die,” McCoy said, “and I had hoped my next use would be what took me out.”

It was not an overdose but another medical emergency that helped McCoy turn a corner.

A doctor at UCSF’s Ward 86, where many sought treatment during the AIDS crisis, diagnosed him with Kaposi’s sarcoma, a cancer common in AIDS patients that causes painful lesions. They had ravaged the roof of his mouth and esophagus and scarred his lungs.

McCoy heeded the warning signs and finally went to drug court. He attended harm reduction programs at Stonewall, Ferguson Place, and the Castro Country Club.

In San Francisco, McCoy experienced something he hadn’t in Virginia: empathy. The drug rehab staff he encountered didn’t condemn him, despite his continued meth use, but supported him through his recovery.

After McCoy completed a drug diversion program in 2009, a letter from the late Public Defender Jeff Adachi declared that his criminal record in San Francisco would be expunged.

‘Principles, not personality’

The D8 supervisor race will be one of the most closely watched, and likely one of the most expensive, in San Francisco next year. Another prominent contender, business owner and event organizer Manny Yekutiel, announced his candidacy last month, raising $120,000 in his campaign’s first 24 hours. (opens in new tab)

Despite his opponent’s fundraising lead, McCoy could prove formidable in the race, given his prodigious connections across the city’s moderate and progressive factions.

In a statement, Pelosi called McCoy a “trusted, tested advocate who will bring thoughtful leadership and deep experience to the Board of Supervisors.”

His broad support is reflected in his endorsement list. Among those backing his campaign are Supervisors Matt Dorsey, a moderate, and Connie Chan, from the board’s progressive wing.

Additionally, McCoy has led the city’s two most powerful LGTBQ+ political clubs: the moderate-aligned Alice B. Toklas LGBTQ Democratic Club and the more progressive Harvey Milk LGBTQ Democratic Club. He’s only the second San Franciscan to have helmed both.

Chan said she sees McCoy as a bridge-builder.

“Along the way, I’ve known Gary McCoy to be someone who is independent and who focuses and prioritizes on the policies, not the politics,” she said.

Dorsey, who is also in recovery from a meth addiction and has endorsed a tougher approach to battling San Francisco’s drug crisis, said McCoy’s experiences would serve him well as a supervisor.

“There are sayings in many recovery programs about progress, not perfection; principles, not personality,” Dorsey said. “If you embrace that and make it part of your life, that is an absolute superpower in politics: the ability to not let things get under your skin.”

As supervisor, McCoy said, he would take that balanced approach to focus on solutions to the city’s crises. He wants San Francisco to build housing across income levels but with an emphasis on affordable options for poorer residents. He favors both abstinence-based drug treatment programs and the harm-reduction options championed by his former employer, Healthright 360.

“Handcuffs didn’t get me sober, almost dying several times didn’t get me sober, overdoses didn’t get me sober,” McCoy said. “There should be a balance.”

Instead, he said, it is the people he has met in San Francisco, and the work he’s done to make their lives better, that keep his head above water.

“I think people need to know what they’re getting,” McCoy said of the voters whose support he hopes to earn. “They’re getting a person that no longer lives that life, that has learned from that life, that has done a lot.”