In September, during an otherwise cerebral game-design conference in Berkeley called Metagame 2025 (opens in new tab), two men climbed into a makeshift ring to do battle. One was short and muscular, dressed all in black, the other tall and slender, wearing wire-framed glasses and a Snuggie.

Each clutched a taser knife, a 7-inch rubber blade outfitted with an electric taser that crackled ominously. The rules were minimal: no zapping hands or heads, and every combatant must endure a pre-fight jolt.

It was a best-of-three-rounds match, announced the duel’s organizer, Verda Korzeniewski, a curly-haired 20-year-old who works in robotics. In the ring, one man jabbed forward as the other circled. There was a zap and a yelp from the Snuggie guy. First contact — end of Round 1. They went again, and the beefy guy quickly finished off his opponent with a zap. New fighters rotated in.

Then one knife hissed and went silent. “Shitty Chinese parts,” grumbled Korzeniewski. The combatants switched to rubber swords, while she went home to resolder the tasers. “Back in an hour!”

Device failure happens a lot with first-time taser knife fighters, said Cory Lord, an electrical engineer who has designed those of the type used at Metagame. “There’s so much adrenaline they don’t realize how roughly they’re handling it.”

Over the past year, DIY contact-shock duels using “tasers” wired to rubber or aluminum foil blades have jumped from biohacker side-games to hacker houses and pop-ups, like Frontier Tower’s Taser Knife Fight Club. They also serve as undercard bouts during robot fight nights, which are growing in frequency and popularity as “the most San Francisco sport ever.”

Organizers say taser knife shocks are quick stings that don’t floor the recipient. For many players, the pain is the point; a zap’s the quickest way for the most online generation to feel something unmistakably offline.

How it all began

Despite the growing hype around taser knife fighting, this isn’t a new sport but a revival. Also, the devices technically aren’t tasers, which were created in the late 1960s by NASA scientist Jack Cover, and which fire barbed darts that deliver electrical pulses to seize up muscles. These “tasers” are actually stun guns embedded in mock blades with a voltage that stings rather than incapacitates, according to knife designer Lord.

The dangers are real, of course; people stunned by a taser can fall and hurt themselves, and those with cardiac issues should steer clear. But studies generally report low (opens in new tab) adverse (opens in new tab) outcomes from stun guns. Critics say most studies use (opens in new tab) healthy volunteers — although that likely aligns with the typical taser knife crowd of adrenalin-seeking young people.

The first taser knife fights began around 2013 as an offshoot of “taser tag,” a rowdy game at Grindfest, the annual gathering of the Grinder community, a biohacking subculture devoted to DIY body modifications and cybernetic implants. These matches “were kind of dangerous,” said Jeffrey “Cassox” Tibbetts, a registered nurse and founder of Symbiont Labs (opens in new tab), a subdermal-implant startup. “They’d leave a burn on you.”

The following year, a taser-making workshop was added to Grindfest, and the wattage was dialed down. Participants were told to build “your own knife and then go fight with it,” said Tibbetts.

It became a tradition with written-down house rules, like “No sharp edges or points,” “No boost converters … we don’t want to BBQ anyone’s eyelashes,” and “Ask yourself: ‘Will this harm my friend?’” If the answer was yes, participants were told, “make some changes.”

Grinders fought with swords, rapiers, and even an electrified baseball bat — but eventually, knives became the standard. Women win some of the competitions, Tibbetts said: Taser knife fighting is “not macho, it’s skill-based.”

The games stayed largely underground until Prospera, a libertarian-styled charter city on the Honduran island of Roatán, cropped up in 2020. The isle’s focus on experimental biotech and access to experimental gene and stem-cell therapies attracted Bryan Johnson and his Silicon Valley longevity stans.

The Prospera scene pulled Tibbetts and Lord into the orbit of Gen Z techies, who, like so many Grinders before them, became transfixed by an emerging martial art that literally shocked the conscience.

Emerging from the underground

In recent months, taser knife fights have gone mainstream in San Francisco, thanks in part to the emergence of a robust bot-fighting scene that has taken hold of the city’s tech underground.

Elliot Roth, president of Biopunk Community Lab (opens in new tab), who has built taser knives and organized fights at the Frontier Tower’s Biopunk Unconference basement rave, attributed the appeal to the hard-tech grindcore movement.

“There’s now a release valve for all of this pent up frustration … the ability for people to get out of their heads and into their bodies a whole lot more,” he said. “We’re constantly surrounded by all this AI in the Bay Area, and it’s really important to connect human to human.”

Roth used to be secretive: “The first rule of taser fight club is we don’t talk about taser fight club,” he told The Standard. But recently, he has reversed course. “I’d rather people know about it and be safe. People should never get hurt doing these things. Ever, ever, ever.”

There have been some rules drift since the Grindfest days; some organizers now allow head and limb taps, for instance. But these rules are unevenly enforced. And the fights exist in a legal gray area untouched, for now, by city permits or state oversight, though many require attendees to sign waivers. The San Francisco Police Department Permits Unit and the California State Athletic Commission, which oversees boxing and other combat sports, did not respond to requests for comment.

Korzeniewski, who spent the past two months building the city’s first humanoid Robot Fight Club, was worried about the glitchiness of the bots, so she added taser knife fights as undercard bouts. “I brought the taser knives to distract from robot malfunctions and make it a little more interesting,” she said.

In July, Robot Fight Club took over the Frontier Tower basement. There was a cage ring, pink lights, a Roomba ring girl, and at least $100,000 worth of robots. Between bouts, or whenever a bot hiccuped, taser knife fights filled the gaps.

Inside the cage, Shawn Park, 22, faced off against Nicole Summer Hsing, 24, founder of Arcarae, an AI self-reflection app, and a practicing Muay Thai boxer. The bout was “exhilarating” Park said, “a childhood fantasy” straight out of “Real Steel,” a 2011 movie starring Hugh Jackman and fighting robots. As a taekwondo black belt, “in theory I should be good,” Park said. But he was out of practice thanks to “the tech grind.”

Hsing leaned into the spectacle in a sleeveless crimson top, a sash belt, and wide-leg black cargo pants. Neither used their martial skills. “I don’t like hurting people, believe it or not,” Hsing said. “I was just dodging and trying to get it in.”

It was Hsing’s first time with a taser. “When I heard it, I thought, oh my god, this sounds so scary.” But after a test zap — “it stung but didn’t burn” — she entered the ring and proceeded to win the next two bouts.

“Gen Z are starved for novelty and are willing to pay a lot for experiences,” Hsing reasoned. “Me and my friends talk about this all the time.”

Taser knife date nights

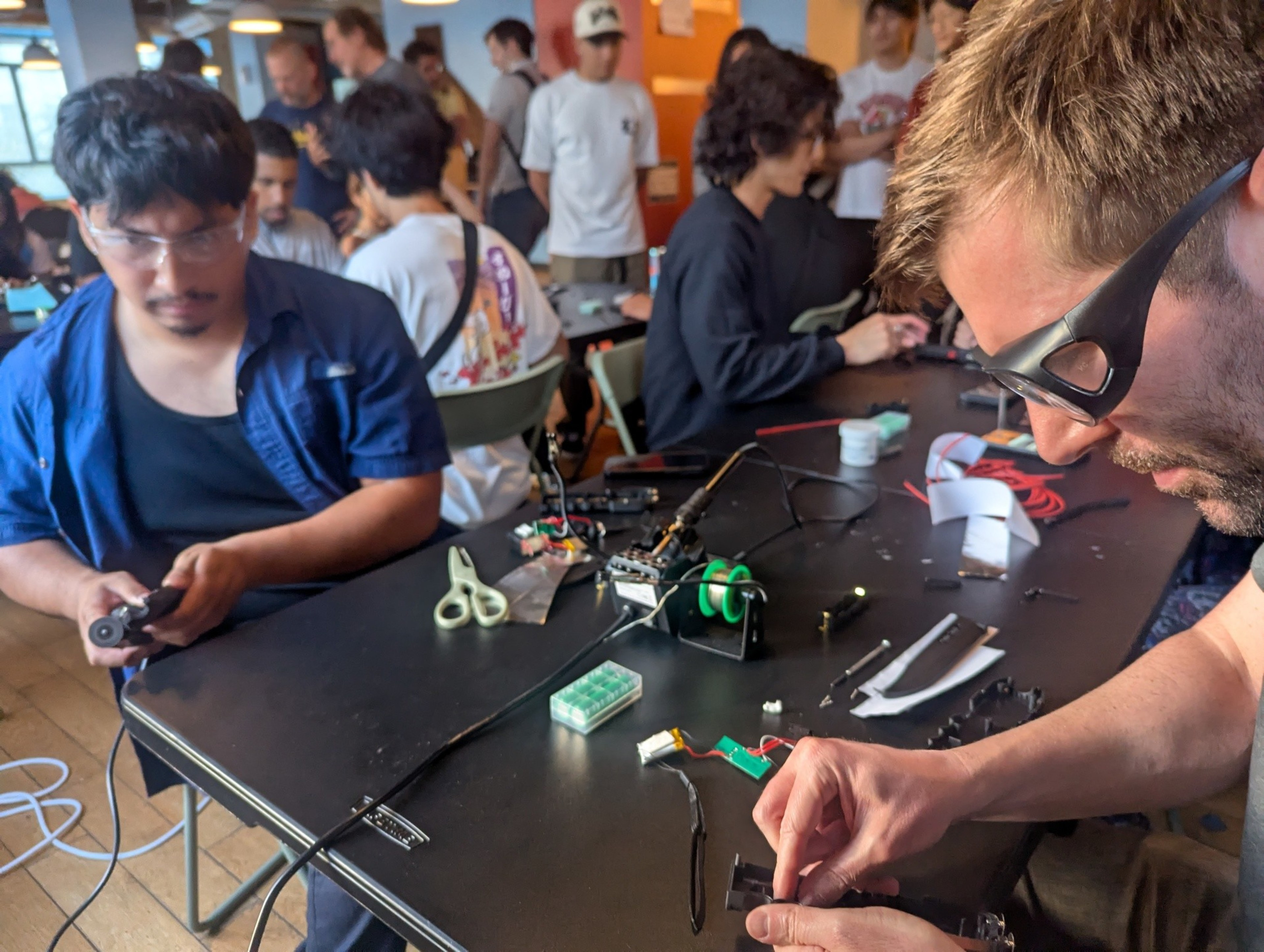

After the July event went viral, Roth planned an old-school build-your-own taser knife workshop, followed by another fight night. “People who saw Nicole fight on social were like, ‘Whoa, that’s insane,’” he said. Roth expected roughly 20 sign-ups but received 170, many from out of state. Two couples — one from Dallas, one from New York — flew in to build knives and fight each other.

“Such a funny date night,” he said. “It was electrifying.”

The class, held at Frontier Tower, ran long, as soldering and dremel skills varied, but the process was part of the initiation into taser knife fight culture, said Roth. “Like a Jedi, taser-knife fighters should make their own,” he said. “There’s a ton of honor and respect among people who compete this way.”

Jessica Jung, who works in an AI lab at gaming company Supercell, showed up just to watch but left dreaming about participating. It was thrilling, she said: the cyberpunk aesthetic, the crackling knives, the drama. “It’s exciting to be where people are bringing the future to life.”

Korzeniewski, who has founded Studio D3lphi, a robot fight club and research company, saw the makings of a larger research project. She considers taser knife duels and humanoid battles an opportunity “to measure how humans fight and how robots fight, and gather data in real time.”

Roth had another way of thinking about the phenomenon. “It’s very heady,” he said of knife-fighting with a taser. “If California is a body, San Francisco is the head. If you’re too much in your head, you need an excuse to get out.”