It’s a Friday morning at Immigration Court on Sansome Street in San Francisco, just a few minutes before the judge shows up, and attorney Diana Mariscal is trying her best not to scare anyone. But from the looks of it, she’s failing.

Standing amid the pews in the court gallery with more than a dozen people awaiting their hearings, Mariscal explains in Spanish that there’s a chance they will all be detained today. It’s the whole reason she’s there — but she doesn’t tell them that. Eyes widen and mouths hang open.

“We hope that this doesn’t happen,” Mariscal tells them. “But if it does, we can help you.”

Mariscal, a lawyer with La Raza Centro Legal (opens in new tab), is today’s “Attorney of the Day,” a program coordinating legal service providers across San Francisco to ensure that pro bono lawyers are at immigration court when there’s a high chance of detentions by Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Today’s hearing fits the bill. It’s at the smaller of the city’s two immigration court sites, where ICE has offices in the same building just a few stories up from the courtroom. In front of the other immigration courthouse several blocks away, protestors often harangue ICE officers as they usher handcuffed migrants into unmarked vehicles. Here at the smaller court on Sansome, it’s easier to detain people without public scrutiny.

Mariscal and her team have deemed this hearing high risk – it’s specifically for undocumented immigrants who’ve been in the country for fewer than two years. None of the immigrants going before the judge today has a lawyer. They are representing themselves — which statistically makes them far more likely to be detained and deported.

Packed into the court gallery, the undocumented listen in rapt silence as Mariscal speeds through the rest of her spiel, a speech she’s given several times to multiple groups of undocumented people this year.

She lays out the day’s worst case scenario: “If the government tries to dismiss your case,” she says, “this is part of a strategy ICE is using to deport people quickly. Ask for a chance to respond.”

She says that last part more than once. It’s critical.

Mariscal speaks in a cheery, confident tone, the way a nurse might talk to a patient about an inoculation they’re about to receive. It might hurt, but you’ll be fine.

The government’s strategy of moving to dismiss asylum cases as a prelude to ICE detention is relatively new, and totally counterintuitive to many migrants. Dismissal once meant that the government had deprioritized deporting someone. Essentially, they were home free. Now it means a lot more work for the attorneys of the day.

After Mariscal wraps up her talk, she and her team from La Raza Centro Legal fan out through the court gallery. They scooch next to people on crowded pews or kneel down on carpets, leaning in close to gather basic information from everyone here for their hearing. Full names, addresses, contact information for family members: all the basics the team will need if ICE detains them today.

These types of hearings were once routine opportunities for judges, asylum seekers, and lawyers to work out bureaucratic details before scheduling a final hearing date to determine someone’s eligibility to stay in the U.S. But since Donald Trump reassumed the presidency, ICE officers sometimes show up outside of these hearings, detaining undocumented people as they leave court. Mariscal and her coworkers have every reason to prepare their non-clients for the worst.

Just after 8:30 a.m., Judge Joseph Park’s face suddenly appears on a video screen. The first case of the day is a family with two young boys. After Park calls their names, the parents sit at a table set up to face a judge who isn’t physically in the room with them. They look to their side at the monitor with Park’s face on it, talking with him through an interpreter.

Respondents continue to trickle into the courtroom. Mariscal and her team catch them as they sit down, reiterating a quick and quietly whispered version of Mariscal’s welcome speech.

The family schedules their next court appearance without incident and leaves the courtroom, oblivious boys in tow. The next respondents to stand before the judge are a couple, Yeison and Yina. They’re both wearing black hoodies with the words “Dare to Dream” in white. Shortly after they’re called, but before they’ve had a chance to present their case for asylum, the attorney for the government moves to dismiss their case. The couple look shocked. Following the instructions Mariscal gave them at the beginning of the day, they request the chance to respond to the government’s motion in writing.

Yeison and Yina leave the well of the court and plop down at the back of the gallery. They look distraught. As swiftly as one can move in a courtroom, Mariscal slides next to Yina and outlines what will happen next. ICE officers are waiting just outside the courtroom doors to detain them, so they must act quickly.

ICE officers await Yeison and Yina in the hallway. Yeison slumps over his phone. He rapidly texts on WhatsApp. “Tengo mucho miedo” — “I’m so scared,” he writes to his brother.

Mariscal asks for whatever paperwork they’ve brought with them. Yina produces a folder full of dozens of pages of evidence she’d hoped to present to the judge, plus paperwork showing that Customs and Border Patrol paroled her because they didn’t deem her a threat. Using her phone, Mariscal photographs every document the couple has on hand.

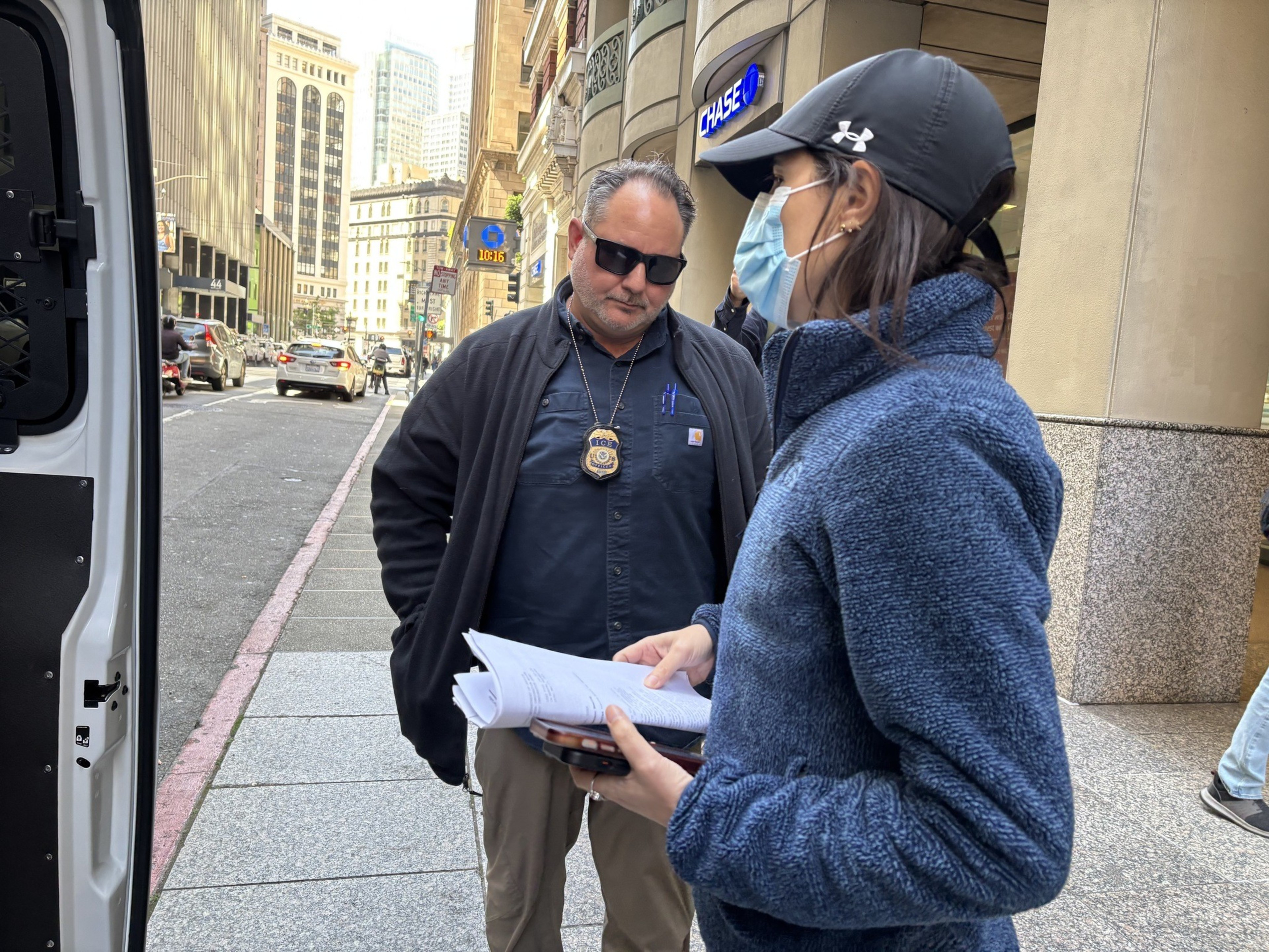

Meanwhile, PF González Montes De Oca, a lawyer in training who works with Mariscal, kneels before the couple and asks them to sign paperwork that will allow the team and a lawyer back at La Raza Centro Legal’s offices to file a habeas corpus petition on their behalf. There’s nothing the team can do to stop ICE from detaining Yeison and Yina once they leave the courtroom, but if it’s successful, the habeas petition can get them released from detention quickly.

ICE officers await Yeison and Yina in the hallway. But they won’t come inside the courtroom. While Yina talks to González Montes De Oca, passing her jewelry and other personal effects over for safekeeping, Yeison slumps over his phone. He rapidly texts on WhatsApp. “Tengo mucho miedo” — “I’m so scared,” he writes to his brother.

In an even-toned whisper, González Montes De Oca explains to the couple what they’re about to experience as they walk out the door. “Four or five face-masked ICE officers will put you in handcuffs,” González Montes De Oca says in Spanish. “But they’re not going to hit you.”

Yina looks determined. “Can we refuse to be taken?” she asks. González Montes De Oca answers no. Yina and Yeison quietly cry.

Over the next hour, a total of eight migrants have their cases dismissed by the government.

As the pews crowd with people realizing they’ll soon be taken by ICE, the courtroom fills with the soft sounds of whimpering and sniffles. The legal team moves quickly from migrant to migrant, collecting information, taking pictures, and bagging valuables.

After about an hour, in the middle of the hearing, Mariscal signals to everyone: It’s time. They have to step outside the courtroom, all together in a group, “because maybe one of them will get lucky and slip by ICE,” she later says.

Three people stand up from the pews and walk toward the back of the courtroom, Yeison and Yina among them. One of the lawyers holds the door open. In the hallway, half a dozen ICE officers stand in a semicircle, waiting for them.

As she approaches the threshold, Yina begins crying loudly. A man she doesn’t know, also walking toward his inevitable detention, puts his hand on her shoulder. He steps out into the hallway and is immediately grabbed by ICE officers, who quickly take him through another door mere feet away. Yina and Yeison hold hands as they walk out, holding onto each other until the last possible moment.

Unlike criminal court, there is no right to free legal help for respondents who cannot afford their own attorneys in immigration court. Private immigration attorneys in the Bay Area charge upward of $13,000, some up to $20,000. So most respondents end up appearing in immigration court without lawyers.

Working with an attorney greatly increases the likelihood that a respondent will win their immigration court case, allowing them to stay in the country. According to data (opens in new tab) from Transactional Record Access Clearinghouse, individuals with lawyers are five times more likely to win the right to stay in the U.S. than those without lawyers.

Access to legal aid varies greatly from court to court. In Miami, the busiest immigration court in the U.S., a little more than 10% (opens in new tab) of immigrants in court for the first time in 2024 had lawyers. In San Francisco’s court, a third of immigrants who showed up for their first hearing date in 2024 had attorneys.

Lawyers serve multiple purposes at immigration court. Aside from giving their clients a better chance at avoiding deportation, they also help the court function efficiently. They file paperwork properly, anticipate what a judge might ask for, and don’t waste time asking the kind of basic questions that an unrepresented respondent asks, such as which form indicates a change of address and where that should be filed. This function is especially important in an immigration court system severely taxed by a yearslong backlog of cases and a recent spate of mass immigration judge firings.

The Justice and Diversity Center, the nonprofit arm of the San Francisco Bar Association, organizes the Attorney of the Day program. It fills some of the gap by orienting unrepresented respondents to what they should expect in court during their hearing, and how to ask for things like more time to find legal representation.

Only a handful of similar programs exist throughout the nation. At most of the over 60 immigration courts in the U.S., respondents who show up without a lawyer are left to fend for themselves. In San Francisco, the city requires that 15 legal service organizations receiving money from the city provide lawyers to cover a certain number of Attorney of the Day slots. The program also maintains a list of more than 100 private attorneys who volunteer when they have time.

Still, there are only enough qualified attorneys participating in the program to cover about 30% of all immigration court hearings locally. The Justice and Diversity Center has reinforced its efforts with non-attorneys, including a court watcher program launched at the end of May. Court watchers are trained volunteers who cover at least some of the other 70% of hearings, and report if there’s an arrest so the program can dispatch a rapid response attorney.

The Attorney of the Day program once had mutually beneficial relationships at court, but that’s changed under Trump. “ We used to have a very good, close relationship with the chief immigration judge,” says Milli Atkinson, director of the Immigrant Legal Defense Program at the Justice and Diversity Center. “We could communicate with them about the needs of the program and the needs of the court and coordinate. It’s much harder to do that under this administration. They just fired the chief immigration judge, so we don’t even know who to reach out to.”

Born in Los Angeles to a family of Mexican descent, Mariscal, now 38, was inspired by her upbringing to become an immigration attorney. “I grew up with immigration issues all around me,” she says. Mariscal spent her early youth between LA and Mexico before her family moved to Oakland amid financial trouble. Nine of them lived with extended family in a studio apartment before her parents could afford their own place.

She wanted to go to law school after finishing college at UC Berkeley, but couldn’t afford it for nearly a decade. Mariscal’s husband is an immigrant from Aguascalientes, Mexico. Together they have a one year old daughter.

González Montes De Oca also got into immigration law for personal reasons. They grew up undocumented living in Los Angeles after their family brought them to the U.S. from Mexico at 8 years old. Trump was elected president for the first time the same year González Montes De Oca finished college. They began organizing legal clinics and know-your-rights presentations. Almost a decade later, they now have legal status.

Prior to President Trump reassuming power, judges, their clerks, and even lawyers for the Department of Homeland Security would work with the Attorney of the Day pro bono attorneys to make the court more efficient. Those days are over.

“ Before, you‘d see judges collaborating with the Attorneys of the Day, maybe saying like, ‘OK, how many unrepresented respondents have you had? I’ll call everyone else who’s represented so that you actually have time to consult with these folks,’” González Montes De Oca says. “ Now there’s like none of that collaboration.”

According to Mariscal and González Montes De Oca, immigration court clerks have recently begun to pressure the Attorneys of the Day to conclude all consultations with unrepresented respondents prior to the beginning of a hearing. That makes it impossible for them to consult with everyone in need of legal help — many respondents show up just minutes before court starts.

In the past, Attorneys of the Day would take respondents out of the courtroom and to another room set aside for legal consultations. But with ICE officers prowling the hallways, this practice now has become dangerous. “They’re really cutting us off at the knees,” says González Montes De Oca.

Even though the Attorney of the Day team and lawyers for the government oppose each other in court, in the past they’ve worked together to efficiently surmount the immigration court’s many procedural hurdles. Now, multiple immigration attorneys say that government lawyers no longer engage in basic pleasantries, let alone work together with opposing counsel to speed along proceedings.

In court this Friday, the government attorney refuses to even share her name with Mariscal. “We’re gonna run into each other again,” Mariscal says. “It’s very normal that you go up to someone and ask their name. Now it’s like, shut down.”

Some respondents react to the fact that they’re about to be detained by ICE with denial. One young man in the first group to leave the courtroom refuses to accept what Mariscal is telling him. “He thought there must’ve been a mistake,” she later says.

Mariscal has seen worse in her time as Attorney of the Day. ”There was one lady who couldn’t physically walk out the door,” Mariscal recalls. “She was just holding onto the doorframe, and we had to close the door and sit her back down and talk to her again, until there was really nothing we could do but walk with her outside.”

The Attorney of the Day team suggests that respondents who know they’re about to be detained leave the courtroom in groups. But some choose to go alone. Among those in court today is Saul, a young Colombian wearing a stylish leather jacket. After the government attorney moves to dismiss his case, he returns to the gallery with a confident smile and tears welling in his eyes. He consults with the legal team and sends a few texts. Then he asks aloud in a Spanish dripping with bravado, “We ready to go?”

Saul vigorously shakes the hands of a couple Attorney of the Day team members and walks out by himself. ICE officers immediately grab him.

A few minutes later, once every remaining respondent has been processed and prepared by Mariscal and her team, it’s time to escort the final batch of people into the hallway.

“Can I resist?” Diana, a young migrant, asks an attorney with the Justice and Diversity Center, who quickly shakes her head no. She suggests that Diana take a few deep breaths to ready herself for what’s to come.

Mariscal and other members of her team lead and follow the day’s last pair of respondents as they walk out of the courtroom and into the hallway. ICE officers swiftly detain one of them – but somehow they miss Diana. So she just keeps walking.

After she makes it past the officers, Diana puts her arm around La Raza Centro Legal case worker Dalia Blevins. The pair walk quickly down the hall toward the elevator. Diana leans her head against Blevin’s shoulder. The pair met less than two hours ago, but now they resemble loving sisters reunited after years apart.

They reach the elevator and press the down button. Before the elevator arrives, a pair of ICE officers catch up, half running and half shouting the name “Jennifer” over and over again.

“Is one of you Jennifer?” the shorter ICE officer says loudly, addressing them. He then turns to Blevins, dressed in a suit and looking the part of attorney. He gestures to Diana. “What’s her name? What’s her name?!”

“It’s not Jennifer,” Blevins replies.

“Well, then what is it?” he demands.

“I don’t have to tell you her name,” Blevins says.

The two ICE officers look at each other in confusion. “We’ve got a picture of her. Even if we have her name wrong, she’s on our list,” the shorter ICE officer says. He consults a piece of paper he’s holding. “Is her name Diana?”

Before anyone can respond, the attorney with the Justice and Diversity Center appears and says, “I’m her lawyer, do you have a warrant?”

“We do. She’s coming with us now,” the shorter ICE officer says.

The attorney insists on seeing the warrant. When the shorter ICE officer claims that he never said they had the warrant with them, the scene descends into a loud back and forth about who said what. The elevator comes and goes, and Diana holds tight to Blevins. The bickering continues until the taller ICE officer speaks up, asking for everyone to calm down and promising to go get the warrant.

“Can I resist?” Diana, a young migrant, asks an attorney with the Justice and Diversity Center, who quickly shakes her head no. She suggests that Diana take a few deep breaths to ready herself for what’s to come.

After he departs, the crowd stands by the elevator in awkward silence. The shorter ICE officer, who’d just been shouting at Diana and the legal team, begins to try to make small talk with them. To no one in particular, he casually remarks that he thinks the building is haunted. No one responds.

The legal team’s insistence on seeing a warrant is not simply obstinacy. There’s a real chance that ICE has confused Diana with someone else. Mariscal says that in the past, security guards in the building have told her she doesn’t “look like an attorney.” On this day at court, ICE officers approached to ask if she was on their list of people to be detained. “That happened to Blevins and myself,” Mariscal says. “Just because we’re brown attorneys.”

A few minutes later, the taller ICE officer returns with a warrant and hands it to the attorney with the Justice and Diversity Center. She looks it over and passes it around to the other members of the Attorney of the Day team. It’s legit. The ICE officers take Diana back down the hallway and into custody.

Afterward, as the legal team debriefs, the Justice and Diversity Center attorney sneers as she remembers the feeling of the warrant in her hand. “It was still warm,” she says. “They didn’t have it when they said they did. They had to run back to their office and print it out.”

While the drama unfolds at court, across town at the La Raza Centro Legal offices in the Mission, senior staff attorney Jordan Weiner is quickly writing a group habeas corpus petition that could get all of the day’s ICE detainees out of detention. Marsical and her team have texted her every photo of the new detainees’ immigration documents, like their notices to appear in court. She’s typing as fast as she can — every minute counts.

Weiner races to file the habeas petition before ICE moves the detainees to a detention center outside of the state. Weiner is able to represent detainees in California, but not in Texas or Arizona, where she’s not a member of the bar. Earlier this year, she filed one petition late, leaving a detainee stuck in a detention center in Southern California for three weeks. With luck, a sympathetic San Francisco federal judge will see the petition today and order the detainees’ immediate release.

While the government has been changing its tactics to increase detentions, so too have immigration attorneys. Habeas corpus petitions challenge the legality of imprisonment in federal court. Recently immigration lawyers filing habeas petitions claim that ICE doesn’t have the legal right to detain undocumented immigrants previously processed by Customs and Border Patrol, unless those immigrants have committed a crime or have been ordered deported in court. Essentially, they have the same rights of due process afforded to U.S. citizens.

The move is a kind of venue switch of its own. Unlike in immigration court, federal judges aren’t subject to the whims of the Trump administration’s policies. A preliminary federal court ruling on a habeas petition can free a detained migrant instantly.

As of June, Weiner had never filed a habeas petition by herself in her life. Now she’s filed them on behalf of dozens of people.

Trump’s mass deportation campaign means never-ending, urgent work for Weiner. Through much of the summer, she worked 75 hours per week. “ I‘m trying not to let people that I supervise know, because I don’t wanna set a bad example for them,” she says later. “ I get a lot of questions from the immigration lawyer community about how I’m doing this. And I wonder how much of the answer is just like, not having good work-life balance.”

So far, every one of Weiner’s habeas petitions have been successful. Every time she’s asked a federal judge to release a new ICE detainee, they’ve complied. And today is no different: At 11:54 a.m., Wiener submits the group habeas for every one of the eight detained during Mariscal’s roughly two and a half hour hearing.

By the evening, ICE releases all of them.

Saul, the 26-year-old who faced his ICE detention with swagger, came to the U.S. almost three years ago. A former member of the Colombian military, he fled his home country after members of the armed rebel group FARC showed up at his parents’ farm, dragged him outside of their home, and told him to leave immediately.

Since arriving in the U.S., Saul’s worked at a series of odd jobs before landing at his current one, a cook at a Japanese restaurant in the South Bay.

Prior to his day in immigration court, Saul was aware of Trump’s mass deportation efforts. He’d seen videos of ICE raids in southern California. But he wasn’t worried about his own court appearance. “I never thought that would happen in San Francisco,” Saul says in Spanish.

When the government moved to dismiss his case and the Attorney of the Day team told him he was going to be detained by ICE, the first person he contacted was a coworker at the restaurant who had become a maternal figure for him in the U.S. He wanted to make sure his shift would be covered.

“ICE is going to detain me,” he texted. “Tell the restaurant managers.” His bosses had given him the morning off for his court date, and expected him to work that evening.

In spite of his outward confidence, being detained by ICE shook him. “When they handcuffed me, I felt like the worst criminal in the world.” Saul says, “on the inside I was scared. I thought I was going to jail.”

While in ICE custody, Saul didn’t eat the frozen burrito or potato salad he was served. In part because the food looked bad, but also because the thought of being sent back to Colombia preoccupied him. “One has to accept they’ll do with you what they want, but I didn’t want to go back to my country,” he says. “I felt like the world was collapsing on me.”

Saul sat in ICE detention for 11 hours before Weiner’s habeas petition on his behalf was processed. He was released at 9 p.m. that night. While they were letting him go, ICE officers did not mention the pro bono legal team’s work or the habeas petition.

“They said to me, ‘You’re not in a gang, you don’t have any legal problems,’” Saul says. “‘You don’t have problems with the police. So we’re going to let you go.’”

Mariscal and González Montes De Oca say that they’d never seen so many undocumented people get detained by ICE at court on the same day. But their collective efforts along with lawyers from the SF Bar Association and Weiner’s fast paperwork resulted in the release of every single one of them. At first blush, their day at immigration court was an overwhelming success.

“We had a profound impact on their lives. And it was still insufficient,” attorney PF González Montes De Oca says. “There are so many people who aren’t even getting this. That’s something difficult to consistently think about and bear.”

But the work is triage, and these victories are temporary. The habeas ruling that freed these eight people from detention is only a preliminary reprieve. None of the habeas cases that Weiner has filed over the last few months has reached a final conclusion.

There’s a real chance that a higher court could issue a ruling invalidating the actions of San Francisco’s federal court, which thus far has been sympathetic to the plight of migrants detained by ICE. If this happens, everyone Mariscal helped could end up in detention again.

“We had a profound impact on their lives. And it was still insufficient,” González Montes De Oca says. “There are so many people who aren‘t even getting this. That’s something difficult to consistently think about and bear.”

The Attorney of the Day work is vital, but it is also additive. It taxes the lawyers that take it on. The more time Mariscal and other attorneys spend triaging for the newly detained, the less time they have to work on building winning asylum cases. “These aren’t our clients,” Mariscal says. “This is just additional work that we have that we’re taking on.”

Although La Raza Centro Legal isn’t taking on the asylum cases of anyone who they helped on their shift at court, the attorneys are continuing to help those immigrants stay out of ICE detention by litigating their habeas cases, as well as restraining orders to prevent ICE from redetaining them.

For Saul, the hearing was just the beginning, not the end. “I’m always scared right now,” he says. He still doesn’t have a lawyer. “I feel like I’m always walking a tightrope.”

But his praise for what the Attorney of the Day team has done for him is unqualified. “They were a blessing,” he says. “They were like angels who came to save us.”