When Liz Cahill woke Oct. 30, her phone was flooded with dozens of messages from people panicking that they’d been kicked out of her Facebook gifting group.

The Buy Nothing No Rules San Francisco group, which has more than 116,000 members, requires a lot of attention from Cahill and two other group administrators. But as she investigated the messages from users fretting about why they could no longer give away or receive second-hand items, it became clear that the situation was dire: The entire group — on which everything from weathered baby clothes to expensive electronics and, once, a pickup truck have been exchanged — had been shut down.

Buy Nothing may appear to be a casual grassroots movement, inspiring thousands of Facebook communities dedicated to neighbors giving and receiving free stuff. But to the people behind the Buy Nothing Project, the umbrella group (opens in new tab) that sparked it all, Cahill and others are copycats who stole their idea, their trademark, and, ironically, their chance to reel in revenue from the giveaways through the official Buy Nothing app. (opens in new tab)

Cahill’s Facebook group, which she runs with Lewis Baden and Aidan Grimshaw, had been removed due to an automated takedown request for trademark infringement. It was just one casualty in a mass elimination of groups (opens in new tab) whose names include “Buy Nothing” but haven’t registered with the official Buy Nothing Project.

The organization last month published a blog post explaining its rationale (opens in new tab) for the takedowns as protecting its “mission, the experience of our members, and the intellectual property we have built over the 13 years of growing this movement.”

Liesl Clark and Rebecca Rockefeller started Buy Nothing in 2013, and the idea quickly gained steam. They shepherded thousands of other groups into existence, laying out rules for how they should operate, but didn’t register (opens in new tab) the “Buy Nothing” and “Buy Nothing Project” trademarks until 2022. Around that time, they launched an app (opens in new tab) to free their movement from Facebook’s platform and explore ways to shift from a volunteer initiative to a venture for which they would be paid.

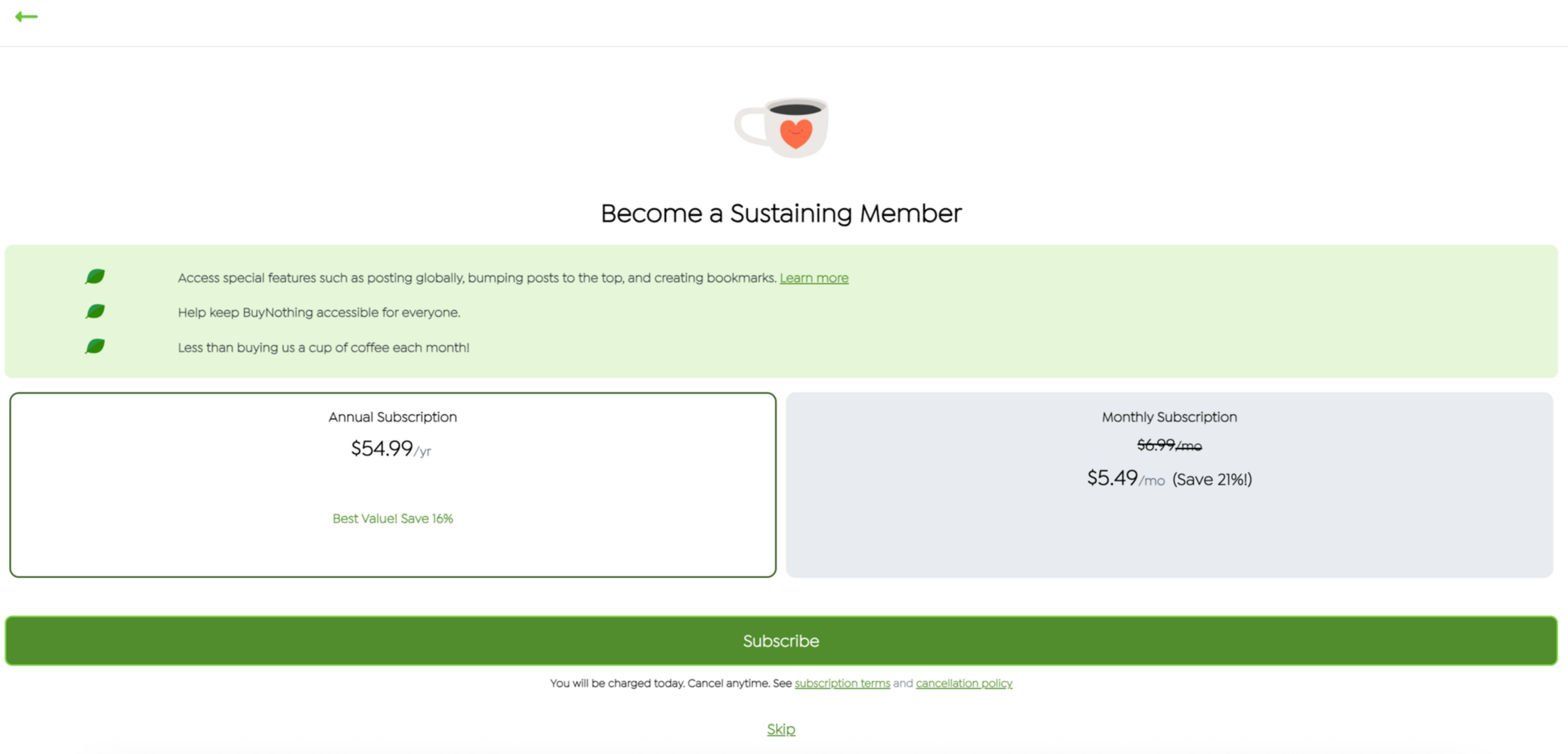

But the app — which prompts members to sign up for $54.99 a year, though they also have the option to join for free — struggled to attract users. Some dedicated followers were enraged at what they saw as an effort to make money that was in conflict with the project’s original mission, as documented in a 2023 Wired article. (opens in new tab)

Clark and Rockefeller didn’t respond to a request for comment.

To Cahill, Baden, and Grimshaw, the deletion of their group felt like an affront to the community. Like many other groups, they had splintered from the official Buy Nothing Project to avoid some of its rules (for example, they wanted to include all of San Francisco for giveaways, rather than making the group hyperlocal).

“We were all like, ‘Holy smokes, this is insane,’” Cahill said. Their group had recently become a hub for people to provide food (opens in new tab) and other resources to those who had lost SNAP benefits, so the timing felt particularly painful. “This shutting down of groups en masse just feels so morally, ethically wrong and against the ethos of the movement.”

Cahill and her fellow administrators contacted the Buy Nothing Project, as well as Facebook, in an effort to reverse the ban long enough for their group to change its name.

A Buy Nothing representative told The Standard its volunteers reach out to independent groups to “help them either align with our standards or rebrand if they prefer to operate on their own,” though Cahill and her partners insist they were not contacted before their group was taken down.

On Thursday, one week after the takedown, the group was restored online, and Cahill quickly changed the name to “Buy Not a Thing No Rules San Francisco (opens in new tab).”

Many of the dozens of other gifting groups in San Francisco have also proactively changed their names, removing direct references to “Buy Nothing” with tweaks like “Buy Absolutely Nothing,” “Gifting in the Bay Area,” or simply “BN.”

Cahill and company don’t know whether Buy Nothing or Facebook made the decision to temporarily reverse the ban on their group. Facebook didn’t respond to a request for comment.

But on Thursday, coinciding with the SF group’s reinstatement, the Buy Nothing Project updated its blog post (opens in new tab) to acknowledge that its recent removals “coincided with the rollback to federal SNAP benefits.” About 1% of the thousands of Buy Nothing groups on Facebook had been affected by the takedowns, the post added, though it didn’t mention whether it had reinstated groups to give them a chance to change their name.

Cahill and her partners believed that using the “Buy Nothing” name was licit, since the purpose of their community is to reuse and recycle, not reap profits.

“There’s a common misconception that trademark laws apply only when something is being sold,” said San Francisco attorney Rohit Chhabra. Courts have ruled that charitable or informational uses can violate trademark rules, so he’s not surprised that Facebook would “act conservatively” and honor Buy Nothing’s takedown requests. “Determinations about likelihood of confusion, fair use, or descriptiveness are judicial questions,” he added, so group owners would need to go to court if they wanted to argue that their name didn’t infringe on the trademark.

Cahill, Baden, and Grimshaw estimate that they collectively spend roughly three hours every day making sure that their spinoff group runs smoothly and is free of scams or inappropriate posts. The founders of Buy Nothing have said that they’ve spent up to eight hours a day working without pay.

To that end, Cahill doesn’t begrudge Buy Nothing for launching an app in an effort at financial stability for its founders. But she believes that taking down unregistered Facebook groups like hers is unconscionably ruthless.

Cahill is “still deeply shaken by the whole ordeal,” she said, and fears for other groups that may not have gotten a chance to change their name. Ultimately, she believes the movement’s idea and impact transcend the original brand.

“This has turned into this mission-oriented, circular-economy movement,” she said. “I don’t think anyone owns the idea of giving and receiving free stuff.”