When you visit a Bay Area coffee shop, it’s almost a foregone conclusion that you’ll be able to order some form of espresso on the menu, whether as a latte, a cappuccino, a macchiato or an americano.

Some 45 years ago, that was not the case. That’s when an Italian elevator repairman in Oakland named Carlo Di Ruocco—new to town and yearning for a traditional cup of espresso—lit on the idea to import espresso machines from Italy and sell them to local restaurants and cafes, who were wholly unfamiliar with the drink. By the mid-1980s, Di Ruocco had established a roastery called Mr. Espresso and began selling his Italian-style espresso beans to Bay Area dining destinations like Chez Panisse.

Since then, Mr. Espresso has built a reputation as the company that helped to popularize the drink itself. To mark the occasion, it’s opening its first ever brick-and-mortar shop, the Caffe by Mr. Espresso—slated for late May.

The Standard spoke to Di Ruocco’s son, Luigi, who, along with his brother John and sister Laurence, now helm the Oakland coffee roasters. He said his father—who hailed from Salerno, a seaside town on the Gulf of Salerno—had apprenticed for a coffee roaster who specialized in the Italian tradition of roasting by oak wood fire, something the elder Di Ruocco went on to pioneer in the Bay Area.

After a brief stint in Paris with his wife, Marie Françoise, Carlo Di Ruocco followed his brother Franco to the Bay Area after Franco enrolled at UC Berkeley. The couple settled in Alameda, where Carlo began tinkering with espresso machines in his garage.

Part of Mr. Espresso’s original business model was a remedy for the homesickness Di Ruocco felt for Salerno. In the 1970s, there were few places in the Bay Area outside of North Beach to enjoy a proper cup of espresso, served in its customary miniature mug. The Di Ruoccos relied on the long-gone Caffe Mediterraneum on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, which heralded itself as the “home of the latte” and famously provided a setting for a scene in the 1967 film The Graduate.

“By and large, most people in America had no idea what espresso was at that time,” Luigi said. “With only a couple of sips of coffee in the cup, it was probably a little strange if you didn’t have a proper introduction to it.”

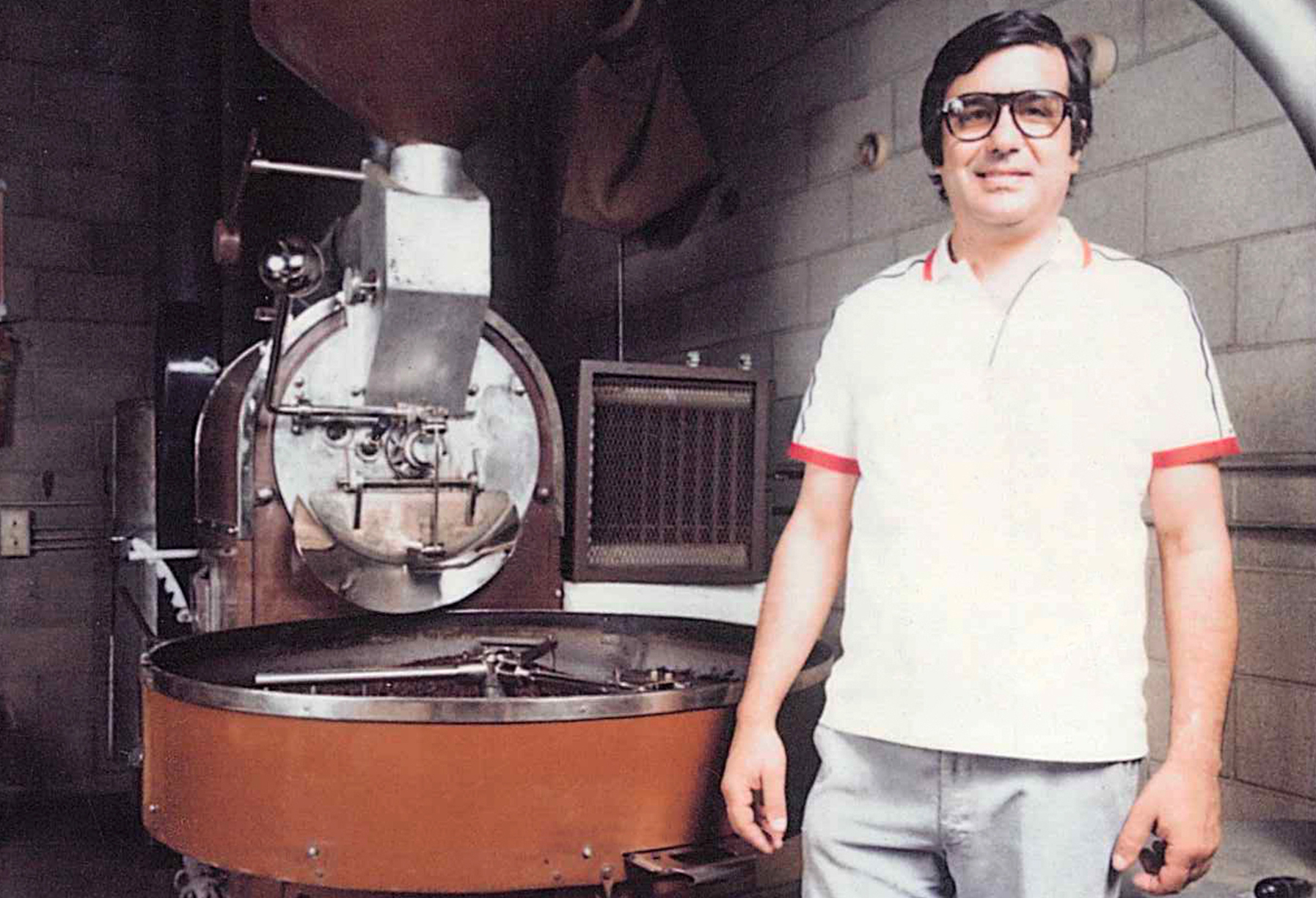

According to Luigi, his father’s mechanic’s training put him in the unique position to help introduce the espresso machine to the Bay. By 1978, because so many fine dining restaurants and cafes came to rely on this elevator repairman, he became a larger-than-life character and named his company Mr. Espresso after a nickname his neighbors had given him when he had begun roasting coffee at home.

Of course, Di Ruocco wasn’t the first to introduce local coffee drinkers to espresso. Apart from Caffe Med, Caffe Trieste debuted the tiny cups of coffee to North Beach in 1957. But by teaching restaurant owners to fish, so to speak, through his importation business, he helped put espresso on the map by proliferating Italian espresso machines and commercializing his espresso beans.

In 1982, Carlo made the natural transition to commercial small-batch roasting. One of Mr. Espresso’s earliest customers was Alice Waters, who began serving Carlo’s espresso at her highly influential farm-to-table restaurant in North Berkeley, Chez Panisse, in the mid-1980s.

At the same time, Carlo introduced espresso to Chez Panisse’s executive chef, Paul Bertolli, who went on to serve it at his Cal-Italian eatery, Oliveto, in North Oakland. Chef Bradley Ogden, former executive chef at the Campton Place Hotel in Union Square, also bought Di Ruocco’s machines, later bringing them to his acclaimed Lark Creek Inn in Larkspur.

In the decades since, of course, America is practically drowning in a sea of espresso, but Mr. Espresso’s roasting process still stands out—starting with its heat source. A typical American coffee roaster is fueled by gas. The roasters at Mr. Espresso contain a chamber beneath the drum that’s loaded with oak wood and set aflame at 1,000 degrees or higher.

Why does the Di Ruocco family stand by wood-fire roasting after all these years? Luigi explained that oak has a high moisture content that creates a more humid environment, which in turn roasts the coffee beans at a slower rate. That explains why the Oakland roaster’s flavor profile tends to be less acidic, fuller-bodied and sweeter—the ideal flavor profile for espresso.

Through the years, Luigi said his father stayed true to the Neapolitan style of espresso he grew up sipping—a medium dark roast that grows darker as you travel south along the Amalfi Coast. To this day, Mr. Espresso still imports Italian espresso machines, but they’re best-known locally for roasting single-origin espresso and blends.

Luigi said he worked at Mr. Espresso as a teenager, mostly handling coffee deliveries with his mother, but the business didn’t truly pique his interest until he graduated from college in 2001. Today, Luigi and his sister both have children, though it’s too soon to tell whether any members of the younger generation will take on the family business.

In 2007, Luigi launched his own chain of modern Italian cafes in San Francisco. Called Coffee Bar, the original triad of shops has since shrunken to two—one near Montgomery BART Station and the other near Chinatown. The Di Ruocco family will embark on the first official Mr. Espresso-branded cafe in about a month’s time.

“There was always an understanding that having a cafe helped to market and promote your brand, but the stars hadn’t aligned until now,” Luigi said.

First reported by East Bay Nosh, the Caffe by Mr. Espresso has a unique conceit. Rather than queue up and place your order with a barista at the counter, the shop emulates typical espresso purveyors in Italy, where someone at the door takes the customer’s order, the customer brings their receipt to the standing bar, at which point a barista pulls an espresso shot.

“The idea is that you’re never waiting in line—more efficient, less bottle-necking,” he said.

The cafe, a sprawling white space with a sleek wooden bar, will also serve premade sandwiches and salads, as well as pastries from The French Spot bakery in Lower Nob Hill.

Luigi explained that his family resolved to debut the espresso bar a half mile from their roastery in the city the company has called home since it was founded.

“We’re still proud to be operating in Oakland after all these years,” he said.