While much of the city is caught up in a doom loop, there’s another part of San Francisco that’s in a boom loop—its parks.

The Standard toured the site of what will be the largest waterfront park on the southern side of the city with a group of park experts to discuss how to best develop public recreation areas in an equitable way—and the first impressions are dramatic.

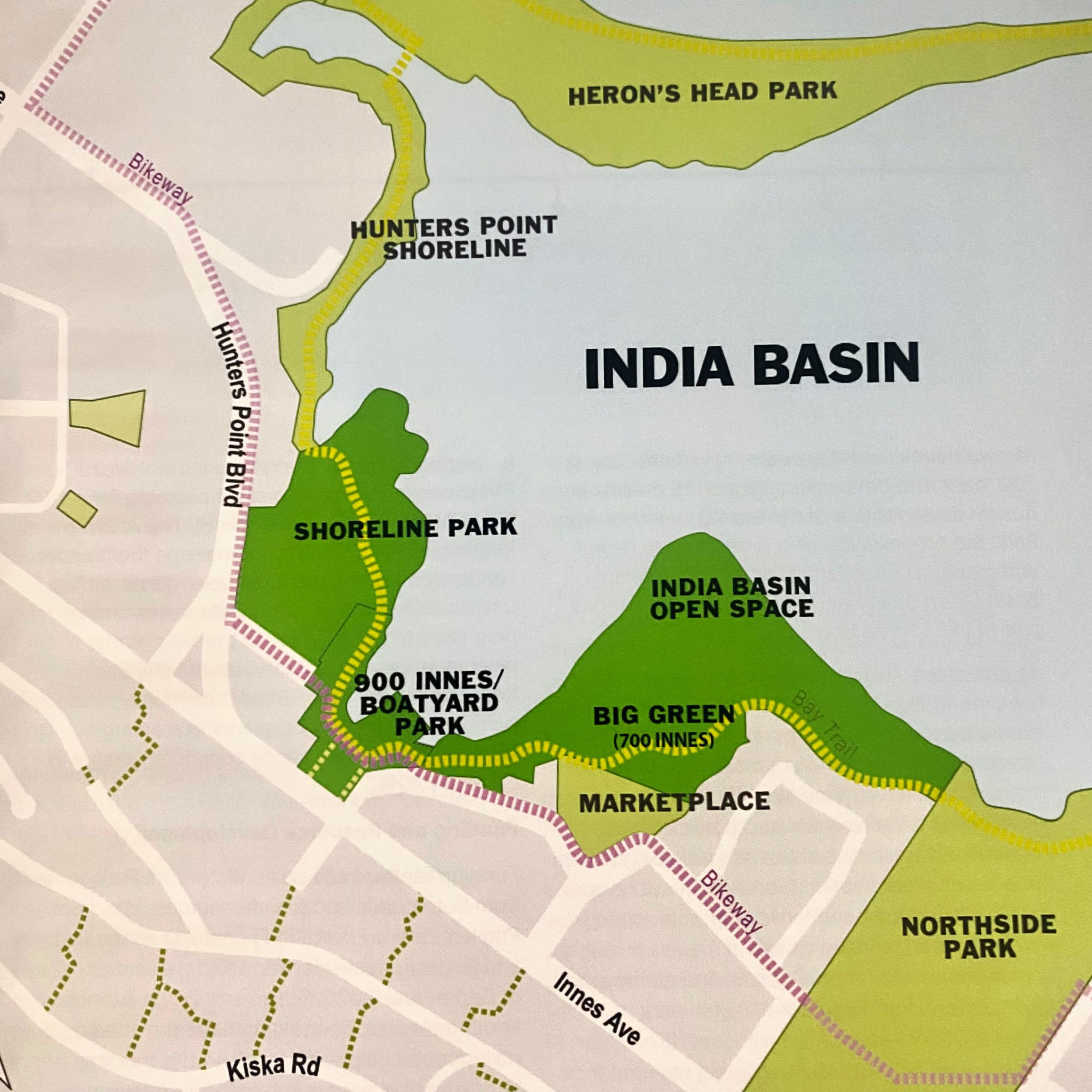

When fully completed in 2026, the India Basin Waterfront Park Project (opens in new tab) will open up 1.7 miles of continuous open space—the last bit of undeveloped waterfront in San Francisco. The project began with the acquisition of 900 Innes Ave. in India Basin and will transform into a 10-acre legacy park that closes a critical gap in the San Francisco Bay Trail.

But the most exciting new park areas of India Basin will open in 2024: After completing cleanup of decades of heavy industrial use, pollution and neglect, construction is well underway on a new waterfront destination at 900 Innes, complete with a new boathouse, a recreational dock for fishing and kayaking, a bikeway and two public piers.

“It’s been a good era for parks,” said Phil Ginsburg, general manager of the San Francisco Recreation and Park Department, which was recently ranked seventh best in the nation and has completed many new parks and renovations over the past year. “But this project is the most ambitious, unique, challenging and important.”

Setting the Bar for Equitable Development

Though India Basin Waterfront Park happens to be the exact same length as Crissy Field, there’s a key difference between the two parks.

“Crissy Field was built for others. This park is being built for the community,” Ginsburg said of India Basin, which is in the heart of the Bayview.

From the start, San Francisco’s India Basin Waterfront Project created an Equitable Development Plan to avoid the displacement of current residents and ensure the community needs are put first.

“This is a community with high crime issues just trying to make ends meet,” said Jackie Flin, executive director of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, Rec and Park’s key partner in the India Basin Project. “They don’t think of a park as for them.”

Flin’s essential role in the project’s development will help to change all that. She’s having ongoing conversations with local residents about what they want from their park—not once, but every step along the way.

Based on feedback from local residents, the major development at 900 Innes/Boatyard Park will include oversized porch swings to look out on the water, a food pavilion with rotating aspirational restaurateurs, basketball courts, trails, restrooms and a pier decorated with a mural by Bayview artist Raylene Gorum (opens in new tab) titled “Lady Bayview.”

It is this cutting-edge approach to park development that inspired a group of some 40 visitors to visit India Basin on Monday. The group—a majority of them out-of-towners—came to study how San Francisco is incorporating “off-park” components, such as workforce development, economic opportunities and arts-and-culture input into a recreation space for a historically disadvantaged community.

The tour and meeting to explore best practices for equitable park development was organized by the High Line Network, a nonprofit organization created after the development of the highly popular New York City park unintentionally caused what is arguably the most rapid gentrification ever in the city (opens in new tab).

Though the city received top marks from the Trust for Public Land (opens in new tab) study, SF’s lowest score was on equity—which came in at 63 points out of 100—but the city is facing that challenge head-on, as San Francisco emerges as a national leader in park development.

SF’s legacy of systemic racism and inequities baked in over generations is on full display in the Bayview community, which has seen much of its waterfront inaccessible and behind chain-link fences as the property of public utilities. It was the filming location for a scene from Last Black Man in San Francisco. In the scene, Jimmie Fails and his friends illegally enter India Basin by scaling fences and breaking into green space that’s not supposed to be theirs to dream about their uncertain futures.

“The tourist map ends before Bayview,” Flin said. “But not for long,” Ginsburg chimed in.

Ginsburg says the India Basin park’s community is 40% Black, with a higher unemployment rate, higher incidence of asthma and lower household income, with 47% of the area’s residents in public housing compared with an average of 6% across SF. The community is also in the 97th percentile of being more likely to have cardiovascular disease—making access to recreation, fresh air and outdoor space all the more essential.

“We want to make sure the park impacts them in a positive way,” said Ginsburg, who imagines the city’s bayfront parks as a necklace of jewels with the India Basin Waterfront Parks as the central pendant, providing a crucial connection to create a seamless waterfront experience for visitors.

Serving the Local Community

The $200 million required for the first two phases of the project includes $125 million of public funding and $75 million of private funding, with the public monies almost entirely secured, according to Ginsburg. To maintain focus on the community, private donors will not see their names inscribed on the park’s features—instead, the donors can pick from a list of heroes the local residents generated.

The park will be staffed by members of the community through a variety of employment apprenticeship programs. Concession operators also be from the Bayview.

The design chosen for the park was the only one to include stairways that lead from the public and affordable housing directly into the park as well as public access to the water and its piers. The area has been historically Black since the 1950s, but there is also a significant Chinese shrimping industry that couldn’t legally access the water for fishing. Given that drowning is the second leading cause of death for Black youth, according to Ginsburg, swimming lessons for the community will also be a component of the recreation activities.

Because polluting industries were concentrated in the area—south of India Basin is the decommissioned Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Superfund site that environmental advocates like Marie Harrison lobbied to clean up—it makes the turnaround for the park all the more spectacular. The necessary remediation was finished last year, and the completion of the next phase of the project will require the removal of a decommissioned Pacific Gas Electric facility.

“We put the stuff here that no one else wanted,” Ginsburg said, referring to the sewage dumps, freeways and PG&E power facilities—some of which still need to be relocated. “But [the location is] every bit as spectacular.”