Just a few blocks from San Francisco City Hall, the aroma of an international feast filled La Cocina’s Municipal Marketplace on a sunny spring afternoon as a team of chefs plated dishes from Algeria, El Salvador, Mexico, Nepal and the Deep South.

Judging by the delicious food alone, all was going according to plan at the women-led marketplace, which was established at great expense with taxpayer money and private donations in San Francisco’s struggling Tenderloin neighborhood.

Back in 2018, when planning began for the Municipal Marketplace at Hyde Street and Golden Gate Avenue, it inspired glowing write-ups in high-profile media outlets and lofty statements from local politicians. The project would not only bring affordable global cuisine to a neighborhood beset by poverty, drug use and violence, proponents predicted, but it would also serve as a hub for La Cocina (opens in new tab), an 18-year-old nonprofit culinary incubator program that supports BIPOC and immigrant chefs working to open their own brick-and-mortar businesses in the Bay Area.

But these days, the dining hall and its colorful parklet are often more than half empty. On a recent Wednesday visit, the open-air seating on Golden Gate Avenue was occupied by four idle smokers rather than a crowd of diners. A pair of security guards shuffled between the entryway and the sidewalk.

With its vividly painted exterior and remarkable culinary offerings, the marketplace appears to be a positive presence in a building that formerly was a defunct post office. Yet, the lasting impacts of the pandemic, a looming recession and the spiraling fentanyl crisis have continued to plague the Tenderloin.

Many of the chefs, baristas and other service workers who earn a living at the food hall say they feel increasingly overwhelmed by the pressure of generating business in the economically depressed neighborhood and the human suffering they regularly encounter on the job.

Mounir Bahloul and his wife, Wafa, operate Kayma Eatery, an Algerian food stall in the marketplace. Though Bahloul said he has a good working relationship with La Cocina, he’s frustrated by how slow business has been.

“No one is making it at the marketplace,” Bahloul said. “The traffic is not there.”

Activation Gone Awry

La Cocina’s Municipal Marketplace was made possible by $2.2 million from the city, $750,000 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and more than $2 million from philanthropic foundations and individual donations. When it was first developed, the 7,000-square-foot food hall attracted not only local attention but also coverage in national outlets like Forbes (opens in new tab).

The marketplace’s champions—including Mayor London Breed, who praised the food hall as a “first-of-its-kind initiative”—predicted it would draw lunch and dinner crowds from nearby office towers and Civic Center. That foot traffic would, in turn, have positive trickle-down effects on the neighborhood by disrupting the violence associated with its open-air drug market and boosting sales at nearby stores.

But four years later, a Covid-driven Downtown office worker exodus has hollowed out the potential daytime clientele.

Mara Blitzer, director of special projects at the mayor’s community development office, explained that when the city granted La Cocina a below-market-rate lease to operate the marketplace beginning in 2021, the arrangement was designed to give the city time to raise funds for an affordable housing project slated to be built in its place—and to provide La Cocina’s chefs with adequate runway to launch brick-and-mortar restaurants elsewhere. However, none of the original chefs incubating their concepts has graduated from the marketplace.

“The businesses are not thriving as much as we expected because the market has changed so dramatically,” Blitzer said.

The Mayor’s Office said it has allocated resources to nonprofit Urban Alchemy so it could assign its “street ambassadors” to the block, and La Cocina employs two security guards to monitor the marketplace during the day. Yet several chefs say the neighborhood’s challenging conditions continue to drive away customers and put pressure on their fledgling businesses.

Faced with the difficult task of activating a square block of the Tenderloin, many people working the marketplace say they feel the burden of fixing this neighborhood has unfairly fallen on them and question the efficacy of this temporary community development project.

Affordable and Untenable

La Cocina’s deputy director, Leticia Landa, said her organization’s hopes for the marketplace have not matched up with reality.

“When we spent millions to build the marketplace, we were 100% excited by the community we were surrounded by, because it’s one of the more affordable places in the city to live,” she said. “Our other target market was the thousands of office workers. That’s definitely not the case now, and every business in the Downtown core of San Francisco is feeling it.”

Pawan Rana, a server working at the food hall, succinctly described the typically sparse afternoon crowd.

“It’s not so good,” he said.

Bahloul told The Standard he feels that his family and the other business owners in the marketplace are still dealing with the aftereffects of the pandemic.

“Nothing is going the way it’s supposed to,” he said. “I can’t make a profit.”

He said he feels that La Cocina asks chefs to pay more money—$500 per month in base rent plus 5% of gross sales, according to a tenant agreement shared with The Standard—than they realistically can.

According to Landa, La Cocina is feeling the financial pressure of its marketplace as well.

“We are in no way covering our costs,” she said. “People are just not eating out as much.”

Jay Foster, who managed the marketplace from summer 2020 until last winter, agreed with Bahloul. He said it was difficult for chefs to drum up enough business during the day and that drawing patrons after sundown proved to be a nonstarter.

“Being there is very limiting,” Foster said. “There’s only really a lunch crowd.”

Landa told The Standard that when La Cocina first submitted a proposal to develop the marketplace, her staff had anticipated a steady flow of lunch and dinner traffic, so they designed a bar to accommodate nighttime diners. Recently, La Cocina has hosted trivia nights and pop-up dinners, which Landa said usually attract around 100 guests.

“But we need that to grow fivefold in order for this to make sense,” she said.

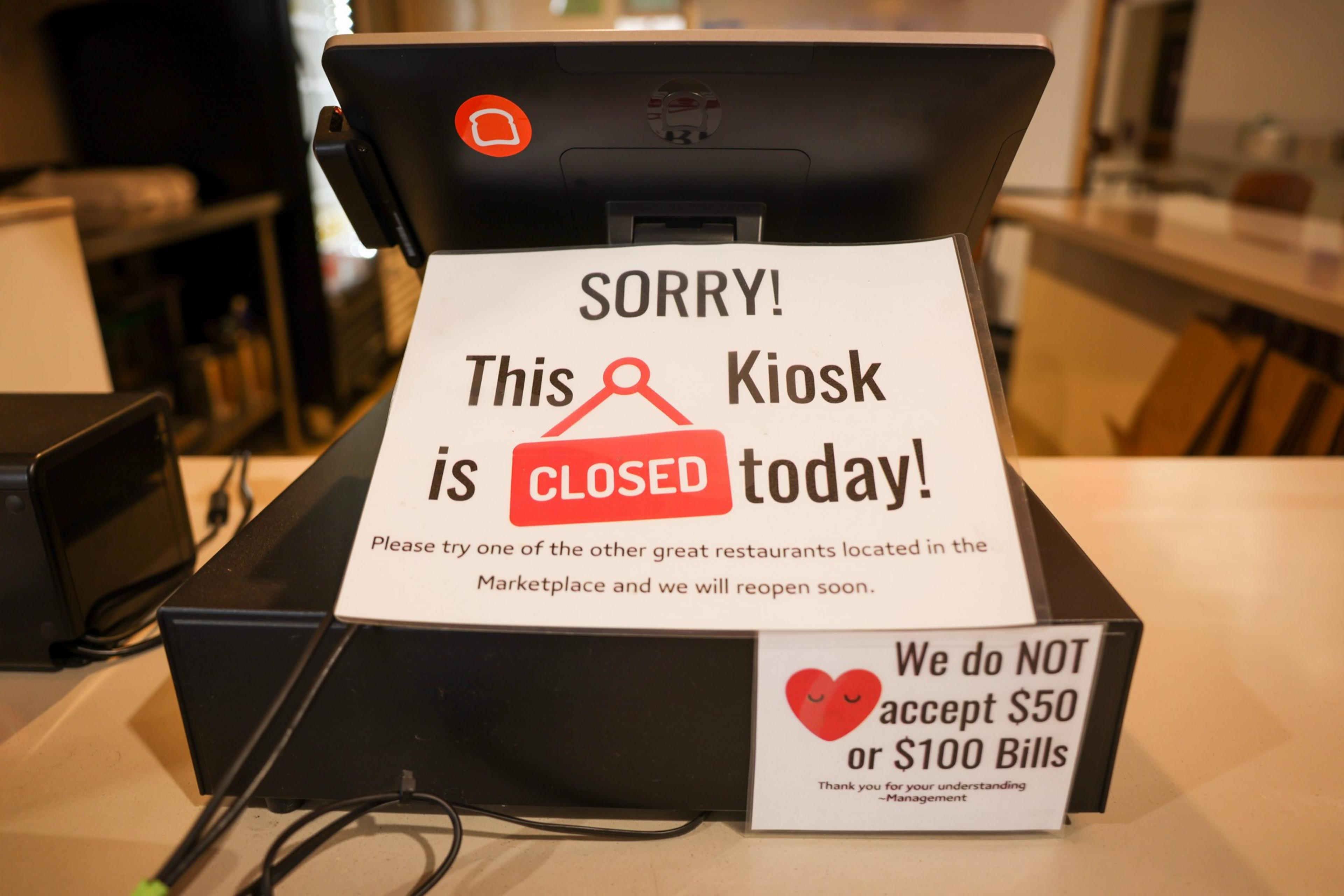

On a typical evening, Landa said only one or two kiosks remain open for dinner.

“The expense of staying open isn’t worth it,” she said. “There’s just not enough people in there.”

Bahloul noted that the daily “rush” only lasts from 11 a.m. to 2:30 p.m., and the marketplace is closed on weekends. Since many people don’t feel safe visiting the neighborhood after dark, dinner is not a viable path to profitability.

“No one wants to hang out in the Tenderloin,” he said. “Tourists stumble upon it and follow their GPS thinking it’ll get better, but it doesn’t.”

“It’s a great concept, but people are afraid to come down here,” said Damian Morffet, who manages security at the marketplace. He said that minutes earlier, he cleared the corner of people using fentanyl—a task he’s been faced with every day over the three years he’s worked at the marketplace.

Tragedy and Trauma

On Sept. 1, 2022, during dinner service at the marketplace, chef Estrella Gonzalez said she had a feeling something was wrong. While working behind the counter at her Salvadoran food stall, Estrellita’s Snacks, she realized a man had been in the restroom for about three hours.

Gonzalez said she alerted La Cocina’s security team, who accessed the restroom and found that the man was unconscious. Gonzalez said the paramedics spent about half an hour with the man before pulling him out of the bathroom. She was later told by a security guard that he had died from an overdose.

“It was very bad to experience,” she told her son Angel, who translated for The Standard. “We had to tell the customers that were waiting for their orders that we had an emergency and needed to close the building.”

Gonzalez joined La Cocina in 2019 and told The Standard she hopes to open her own brick-and-mortar restaurant after her five-year contract is up.

“La Cocina has not mentioned what will happen after,” she said. “At the moment, we are limited because of the shared space, but we stay excited about the future because the people of San Francisco always look to support us.”

Landa said the man’s death and similar incidents have catalyzed a number of changes to the marketplace’s safety policies. La Cocina has limited access to the building, so now there’s one entrance and exit that’s staffed by a security guard at all times. Landa said her team has hosted Narcan trainings to reverse overdoses before they become fatal. Still, she said it’s difficult to create an open and inclusive space while taking safety considerations seriously.

“We want to balance welcoming everyone and be a community space and mitigate risk associated with drug use,” she said. “We’re doing our best, which is not to say that we’re doing it perfectly.”

Urban Alchemy hosts a pop-up tent down the block from the marketplace, and Landa said she feels that while the nonprofit’s presence in the Tenderloin is helpful, its street ambassadors aren’t assigned to stay into the evenings, when drug-related violence tends to foment on the block.

“It’s not their fault, but I do wish we had more coverage,” she said. “But this isn’t just a La Cocina issue.”

The Standard spoke to Landa after Whole Foods abruptly closed its nearby Eighth Street store, citing safety concerns. Landa said it’s disheartening to see a corporate grocery store pull up roots in an already under-resourced area of San Francisco.

“Now there’s this whole group of people who are afraid or unwilling to engage with difficult parts of the community, when it’s so important that people show up for these kinds of spaces and businesses,” she said.

None of the chefs have left the marketplace yet, but Landa told The Standard that chef Tiffany Carter from Creole bodega Boug Cali and chef Bini Pradhan from Nepalese eatery Bini’s Kitchen are focused on building their businesses in other locations. Neither kiosk was open during The Standard’s most recent visit.

The Future Outlook

The marketplace building is still on track to be razed to make way for affordable housing, but Blitzer explained that if the city doesn’t have the funds lined up by the end of 2025, it would consider extending the agreement with La Cocina. If not, she said the city plans to give La Cocina about a year’s notice to vacate. She said there could be some footprint of the former marketplace, particularly if the community advocates for it, but it’s not guaranteed.

“There’s no chance a food hall could afford a building of that size,” Blitzer said. “But I’m brokenhearted about the pandemic with regards to this particular project because it is a fantastic concept.”

The pandemic undoubtedly had a major impact on the faltering marketplace, but its overall trajectory reveals the pitfalls of temporary community development projects. Sarello Buyco, the co-founder of Fluid Cooperative Cafe—a trans-owned coffee shop that operates as a pop-up at the marketplace—shared his perspective.

“Older rich white folks want to beautify this neighborhood,” he said. “But the neighborhood is beautiful. It just needs more resources, community and accessibility.”

Acknowledging that the marketplace is still a work in progress, Landa said La Cocina plans to stay attuned to the needs of its community in order to determine whether to keep the project going in a new iteration once the lease is up.

“One of the things I’ve realized after working for 15 years in nonprofits is that sometimes the best plans are thrown out the window when circumstances change,” she said.

Honey Mahogany, a social worker, drag performer and chair of the San Francisco Democratic County Central Committee who ran for District 6 Supervisor in 2022, recognizes the tension underlying this particular project. On one hand, she said La Cocina’s model has great potential, but on another, it’s not a panacea for the Tenderloin.

“It creates a sense of activity and prevents folks from conducting illicit activities right outside the door,” she said. “It helps people out of poverty, but that’s one individual at a time. The marketplace in and of itself cannot solve all the issues of the Tenderloin.”

Mahogany explained that future housing developments pose a unique challenge in a city like San Francisco.

“Sometimes those lots can sit empty for up to a decade,” she said. “They can attract a lot of quality-of-life issues and illicit behavior that really hurt the neighborhood. Any sort of activation that turns them from an empty shell to a place that’s full of life is always going to be a positive.”

She said that people should continue to take the Tenderloin into account when developing food halls and other community resources.

“Just because the Tenderloin and other neighborhoods are poor, or have become run down over time, or have been neglected by the city, doesn’t mean they have to stay that way,” she said.