As an EDM mix of Britney Spears’ “Toxic” blasted on Sunday night, Charles Oppenheimer, grandson of the father of the nuclear bomb, jumped around a packed dance floor in SoMa, wearing a glittery green jacket and a T-shirt printed with a giant white atom. It was his 50th birthday, and he was celebrating at the Nuclear Rave, sponsored by SF Climate Week.

Dancing alongside Oppenheimer were around 350 young people, some of whom had no opinions on nuclear power whatsoever and had come for the Atomic Sunrise cocktails they’d seen on Instagram.

The party was the brainchild of Oppenheimer’s friend Ryan Pickering, 37, an energy policy researcher and nuclear energy consultant for Confidential, a consulting firm. Dressed in neon shoes and a windbreaker emblazoned with the name of California’s only nuclear power plant, Diablo Canyon (which generates 9% (opens in new tab) of the state’s energy), Pickering had dropped $10,000 on the rave. “This is the best money I ever spent,” he said.

The point? To spread the good word about nuclear power to young people and get them fired up about California’s recent legislative push (opens in new tab) to approve small modular nuclear reactors, a bill that excludes large-scale fission reactors, considered the gold standard for reliable nuclear power. “SMRs won’t change the needle on clean energy,” he said. He passed out a one-page “zine” at the door, to educate attendees.

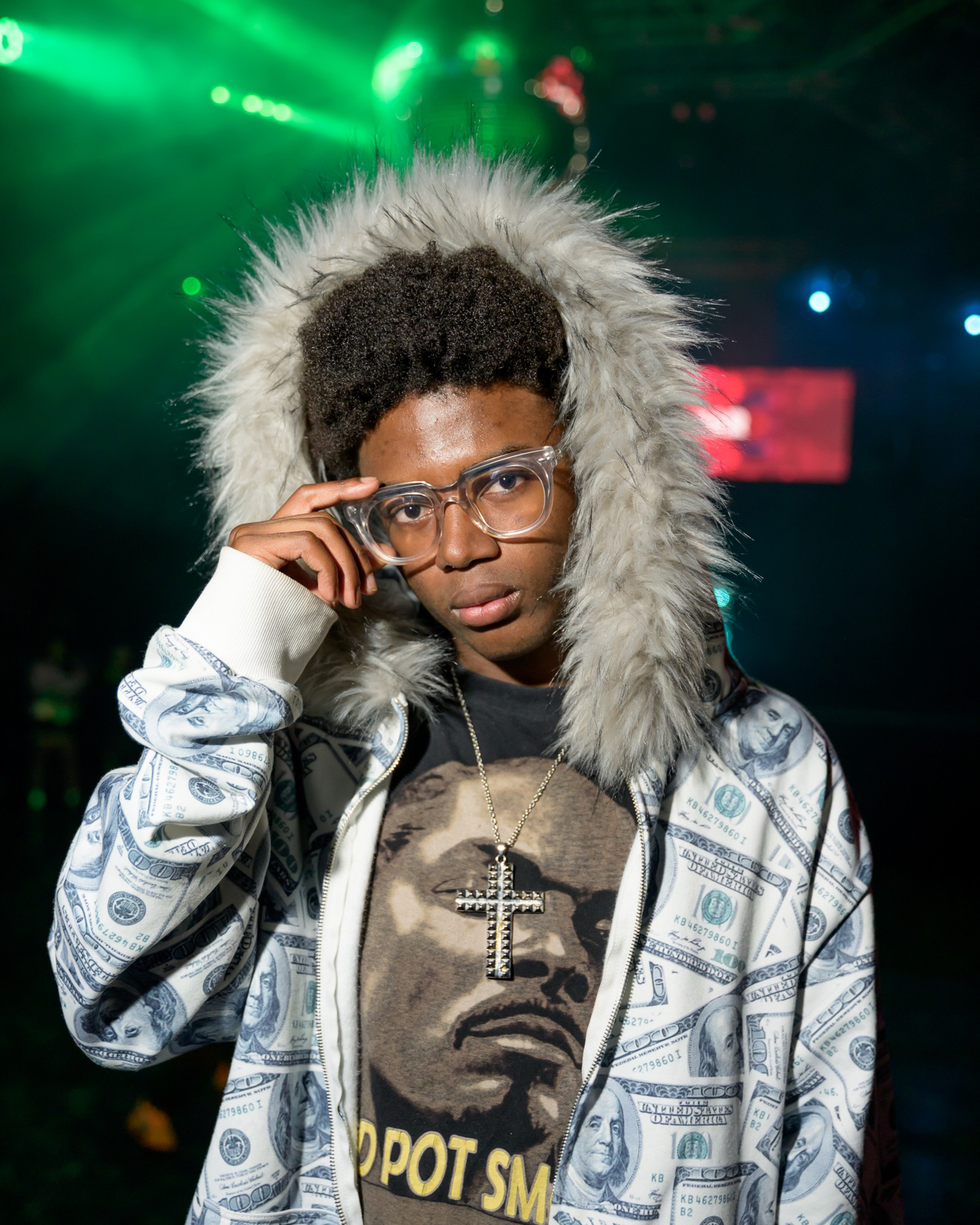

| Source: Niki Williams for the SF Standard

“People should be way less afraid of nuclear energy,” said Oppenheimer, the San Francisco-based founder of the Oppenheimer Project, a nonprofit focused on reframing nuclear power from a doomsday device to a sustainable energy solution. “It’s only bad if you make weapons out of it. It’s good if you can make energy out of this.”

The rave marked something of an about-face for the Bay Area, which has had a strong anti-nuclear stance (opens in new tab) through the Cold War era and beyond and was once a hub of the “no nukes” movement.

But with fuel costs surging, energy needs rising, and climate change causing ever more havoc, a new breed of activists is looking at nuclear — which accounts for 20% of U.S. power generated (opens in new tab) — as a source of clean energy. More than a decade since the most recent nuclear disaster — in Fukushima, Japan — worries that had fueled restrictions and bans are being reconsidered.

| Source: Niki Williams for the SF Standard

The United States has joined 24 other nations in pledging (opens in new tab) to triple nuclear energy capacity by 2050. And for many in the tech industry, nuclear is increasingly seen (opens in new tab)as a necessity to power the AI boom. Amazon, Google (opens in new tab), and Microsoft (opens in new tab) announced separate nuclear energy deals in October. As the writer Elizabeth Kolbert put it recently (opens in new tab), “Fourteen years after Fukushima, fission, for better or worse, is back in fashion.”

In San Francisco, where protesters marched against nuclear power in the ’80s, their kids are now dancing to support it. Grant Mills, a 25-year-old grad student in the nuclear engineering program at Berkeley, helped Pickering promote the rave. Sipping a Cobalt Core cocktail, named for a radioactive isotope, he expounded on the virtues of nuclear energy. “In an ideal world, nuclear power would be treated at the same level as all other energy sources,” he said.

In 2023, Mills founded the Berkeley NiCE Club, which stands for “Nuclear is Clean Energy,” responding to the demand to study and discuss the topic on campus. In fact, UC Berkeley is the only California college to offer nuclear engineering as an undergrad major. (opens in new tab)A chemical engineering student at the rave said nuclear students are referred to on campus as “the nukies.”

Unlike some tech-adjacent SF “raves” that are more like networking events, the Nuclear Rave felt like an actual party, filled with sweat and shouts and dancing. Many of the most excited ravers were NiCe members, dressed casually in cargo pants or Doctor Doom tees. When the LED visuals flashed “#legalize nuclear,” people raised their arms and whooped. At times, the smoke machine, thumping bass, and red LEDs gave the dance floor an apocalyptic feel — very on theme.

Stella Merims, a 19-year-old Berkeley double major in rhetoric and linguistics, with a minor in creative writing, played a set at the party under the DJ name Lot Lizard, part of the Fuzz Noise (opens in new tab) DJ collective. She said she is open to nuclear, with reservations. She finds it unsettling that the recent boom in interest comes from the growing energy demands of AI companies. “As a humanities major, AI is greatly negatively affecting my life, and I’m very worried,” she said. “But there isn’t a way to de-growth it, so we need to find a more sustainable way to [power it].”

Dressed in their rave finest – a striped Bebe dress, a matching bra and pants, and black fluffy boots – Lydia Fife, 21, a movie theater employee, and her friend Maya Williams, a 19-year-old jobseeker, said they came for the dance, not the agenda. They heard about it through Instagram, said Williams, who thought it sounded random. “I honestly know nothing about nuclear power. I’m completely uneducated,” she said.

But Fife has concerns. She said she’d seen the film “Oppenheimer,” and it gave her chills. “I’m definitely scared that someone could do irreversible damage,” she said, noting J. Robert Oppenheimer, grandfather of the event’s organizer. “Nuclear shouldn’t exist. … Like, it’s too powerful.”

That wasn’t exactly the takeaway Pickering was aiming for. His goal is to get California to overturn its 1976 moratorium on building new nuclear (opens in new tab) power plants until a permanent waste solution is approved.

“[There] is a conspiracy against nuclear,” he said. “The adults have blown it, [and] the kids deserve to know.”

A rave probably won’t change policy, nor will it remove nuclear power as the “black sheep” of the energy world, as one Climate Week panel referred to it.

But it might change the vibe. “Kids like to rave,” said Oppenheimer. “Will it change how they feel about nuclear energy? I don’t know.”