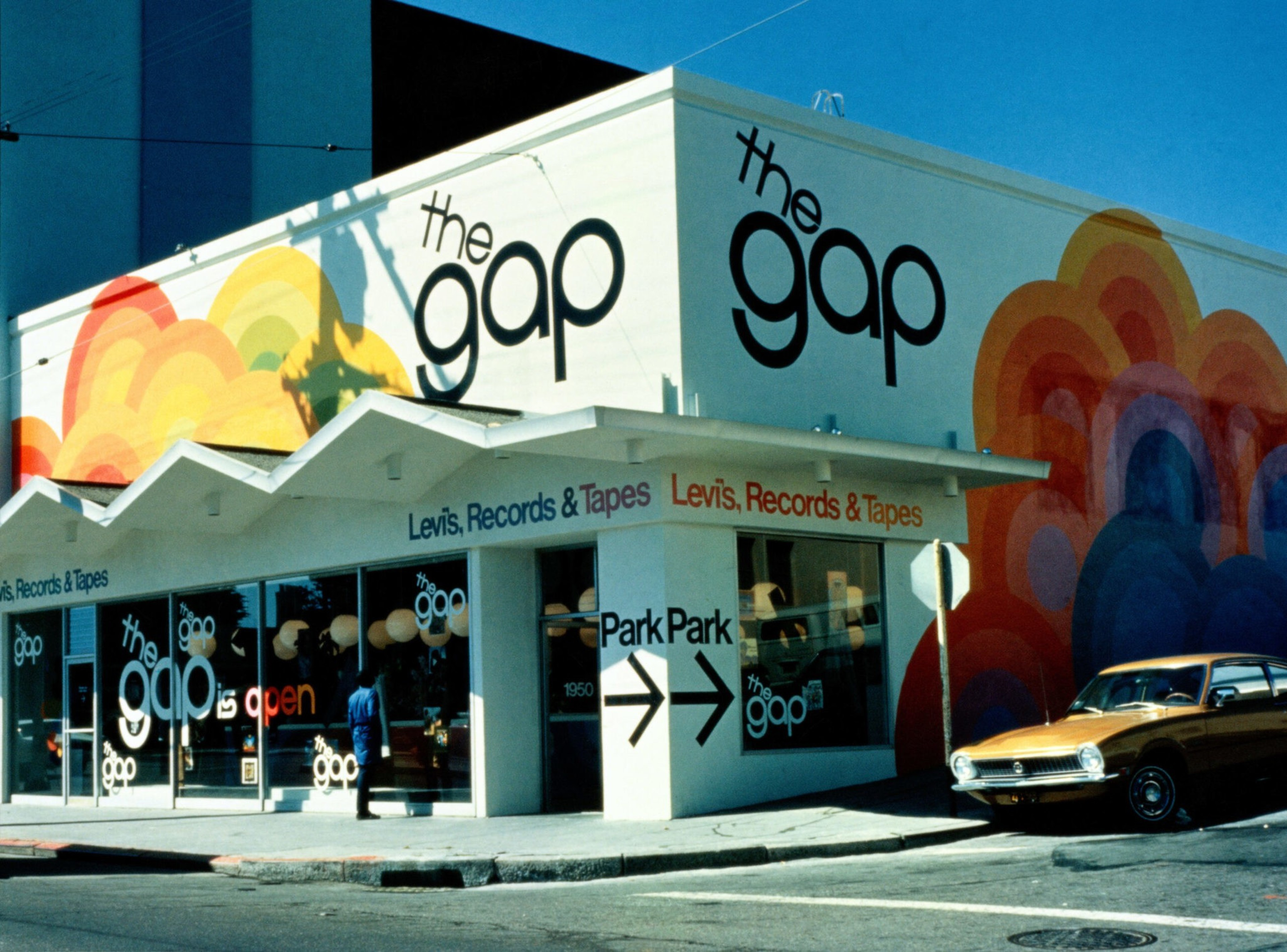

The first ever Gap didn’t carry Gap clothes. It peddled Levi’s, LPs and the idea that shopping at the store would keep you young and cool.

The location, which Don and Doris Fisher opened in 1969 on Ocean Avenue in Ingleside, occupied a storefront in the old El Rey Theatre, designed by accomplished San Francisco architect Timothy Pfleuger. The groovy multicolored concentric circles of the brand’s first logo were meant to replicate the records spinning inside.

Today, the space remains vacant. So does the store at Powell and Market streets, which had served as the brand’s flagship until it shuttered in 2020 along with the Gap stores in Embarcadero Center and Stonestown Galleria.

Only the Chestnut Street store and a recently opened “laboratory” retail Gap attached to the company’s headquarters at 2 Folsom St. remain. While the company hypes the laboratory spaces (opens in new tab)—which include Gap, Inc.-owned brands Athleta, Old Navy and Banana Republic—they are in office space the company already owns rather than a heavily trafficked retail area.

Executive Chairman Bob Martin is serving as interim CEO of Gap, Inc. after the company booted CEO Sonia Syngal in July; she had been brought in after four years of leading the Old Navy brand. In September, Ye, formerly known as Kanye West, severed his already rocky partnership with the Gap brand (though that might be just as well for the company in light of Ye’s recent comments (opens in new tab)). A few days later, Gap, Inc., laid off 500 corporate employees.

In all fairness, Gap is facing struggles that are common to many brick-and-mortar retailers, who were coping with the rise of online shopping even before the pandemic closed stores and sent even more people to the internet for their retail needs.

“The Gap is going through what a lot of retail is going through right now, which is trying to find the right sizing between physical and digital,” said Ari Lightman, professor of digital media and marketing at Carnegie Mellon University. “Gap just couldn’t make the pivot quickly enough.”

But there’s more to the story, too. At a time in consumer culture when selling a story matters more than ever, the veteran purveyor of casual separates can’t decide what it wants to be: online retailer, mall stalwart, urban chic or discount bin. It had a long run as a mainstream fashion staple and ubiquitous pop-culture touchstone—serving as fodder for a popular Saturday Night Live (opens in new tab) sketch (opens in new tab) and making prominent cameos in everything from Reality Bites to Stranger Things—but the pioneering San Francisco brand is finding it can’t run on the fumes of khaki nostalgia alone.

The biggest mall owner in the country, Simon Property Group, has more than double the number of Gap Factory discount stores than there are Gaps, and the group is suing Gap (opens in new tab)—one of its largest tenants—over unpaid rent. Gap’s share price has fallen more than 50% this year alone.

Gap, by all appearances, is falling apart at the seams.

“They don’t really have anything in their armory that says, ‘Look, you know, here’s the weapons we plan to use to grow the business,’” said Neil Saunders, a retail data analyst for GlobalData. Gap, Inc., and the Fisher family declined to comment for this story.

The Roots of San Francisco Cool

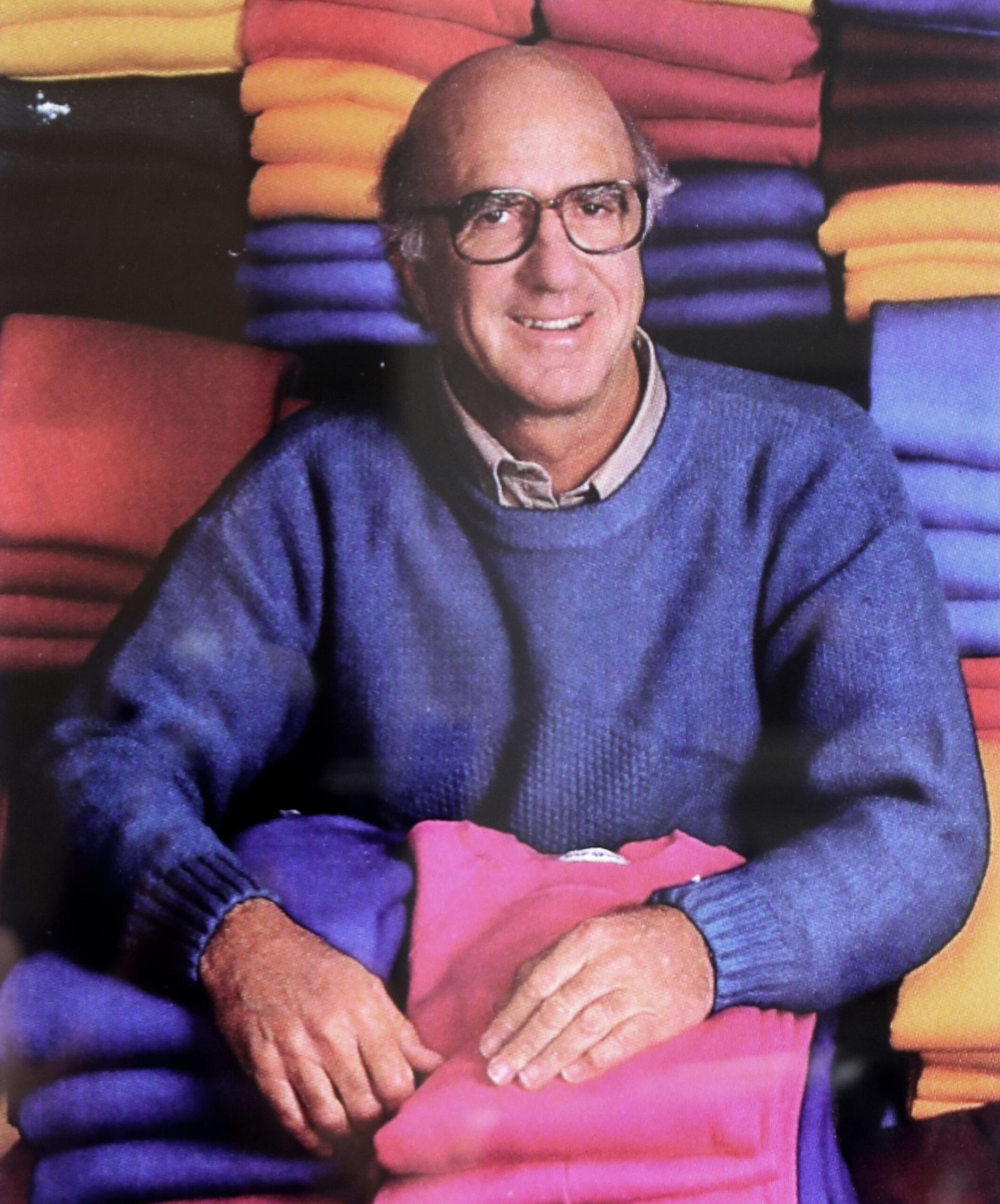

Don and Doris Fisher—who would later become well-known San Francisco philanthropists with their major donations to SFMOMA and other organizations—opened the original Gap store in 1969 as a side project to their real estate business.

Don had the idea for the store after he couldn’t find Levi’s in his size; Doris came up with the name. Meant to imply “the generation gap,” it soon became a phenomenon in its own right with the store’s famous tagline and jingle: “Fall into the Gap.”

One year later, Gap had five locations in California. Five years after that, it had 186 stores across the United States.

Gap, Inc. went public in 1976, and its umbrella of brands have a long association with Northern California.

Gap, Inc., acquired Mill Valley-based Banana Republic in 1983, and it launched the first Old Navy store in Colma in 1994. After acquiring Athleta in 2008, it opened the brand’s first brick-and-mortar store in 2011 on Fillmore Street in San Francisco. Gap, Inc., headquarters remain at 2 Folsom St. in a 15-story tower that includes a terrace overlooking the Bay Bridge with jaw-dropping views.

“It’s part of the heritage of San Francisco,” said Saunders.

Central to Gap’s appeal was the visual aesthetic of its stores. Decades before Steve Jobs introduced the minimalist Apple Store or Marie Kondo built an empire on organization, the Gap was proving the appeal of clean, uncluttered spaces and neatly organized clothes. Don Fisher had the idea to use cubicle shelves along the walls instead of traditional racks and tables, which made sizes easy to sort and find.

“They really knew what they were doing,” said Alexandra Lange, author of Meet Me by the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall. “That very clean look — and the piles of colored sweaters and T-shirts — it made what were very simple clothes extremely appealing.”

A recent trip to the Gap on Chestnut Street demonstrates how far it has strayed from these roots.

Giant construction bags stand in the middle of the floor, Ye’s line of Yeezy sweatshirts and T-shirts piled in an impossible-to-sort heap. “It’s supposed to look messy,” one of the clerks explained. “So you feel like a kid.”

Clothes hanging on the walls had visible creases, crumpled from being in boxes. Jeans and separates hung on racks—but so did floral rayon. The store didn’t have a story.

Dead Malls, or Dead Brand?

Mickey Drexler became the Gap division’s president in 1983 and CEO of Gap, Inc., in 1995, executing a hugely successful transition from hip boutique chain where one could buy Levi’s to a mass-market private label. The khaki craze supported a rapid expansion of the brand, with many stores opening in close proximity to each other in malls and shopping centers.

“Peak mall is peak Gap,” said Lange. “The mall and the Gap eventually overexpanded.”

With Don’s brother Bob, who worked in construction, helping build out the locations, expansion kicked into high gear with the Fisher family’s deep property experience.

“I’d already done pretty well in real estate,” Don Fisher writes in his autobiography and business chronicle Falling Into the Gap. “But what did that have to do with retail?”

Yet according to Mark A. Cohen, director of retail studies at Columbia University, the company expanded much too fast.

“Even though it was the Don and Bob show opening stores everywhere, he [Drexler] knew damn well they were diluting the brand equity of the Gap,” said Cohen, who also worked for Gap as a company manager from 1977-79. “He was the CEO, and he should have stopped it. But he didn’t.” Drexler could not be reached for comment.

The shopping mall subsequently went into decline in the early aughts. While there were once 1,500-2,000 malls across the U.S., the number is now around 800, according to Lange. Gap, as one of the mall’s biggest tenants, suffered, too.

But the stores might not be such a liability for Gap if the brand gave a reason for people to come inside.

Across the way from the Chestnut Street Gap store, Marine Layer accepts old T-shirts for recycling—you get $5 off a new tee when you drop off your old one. A few doors down, Madewell offers a jean recycling program, encouraging people to bring in used denim, as well as one-on-one styling.

Gap has failed to re-imagine its costly stores as part of a community. “You could reap a lot more benefit out of it than simply somebody going to pick up a pair of jeans,” said Lightman.

The Fisher Fingerprints

Don Fisher died in 2009, but the family remains the largest stockholder (opens in new tab) in the company and Don Fisher’s sons Robert and William Fisher serve on the board of directors, as does Doris Fisher as an honorary member. John Fisher, the third and youngest son, previously worked with the company and is now the owner of the Oakland Athletics baseball team.

“The Fisher family is still very involved,” Saunders said. “And they’re the common ingredient throughout Gap’s decline.”

Don Fisher’s version of the company’s culture in Falling Into the Gap emphasizes fast pace and quick turnover: “The Gap is definitely an exciting, high-energy, high-speed, high-result company with demands that eliminate those unsuited for the pace,” Fisher wrote.

But critics say Gap’s company culture today is stultified. “It’s a culture that doesn’t really seem to favor innovation,” Saunders said. “It seems to talk in riddles most of the time and not set out very clear strategies.”

A May 2022 earnings call transcript (opens in new tab) seems to prove his point: “When spring product finally began to arrive in March, and it will maybe continue to experience softness, we conducted a deep diagnostic of the business, and it became apparent we also had product acceptance issues,” said Syngal.

The Carousel of CEOs

After the many successes of Mickey Drexler—who left the company in 2002 to helm J. Crew and has since cofounded the clothing line Alex Mill with his son—Gap, Inc. has yet to find the right leadership.

Paul Pressler from Walt Disney Parks came on as CEO after Drexler’s departure. Then came Glenn Murphy, the CEO of a drugstore chain, who cleaned up the balance sheet but also did not know how to run an apparel business, according to Cohen. Subsequent CEO Art Peck also proved unable to restore momentum.

“Without leadership, you got nothing,” said Cohen. It’s ironic that the retailer that once represented the entirety of Gap’s merchandise—Levi’s—is faring better than Gap itself by capturing a niche market and not trying to be everything to everyone all at once.

“Levi’s has a phenomenal innovation and data science team. They have customization,” Lightman said, noting that even though it was born and bred in San Francisco, the crucible of internet innovation, “Gap was a laggard when it came to technology.”

Lolita Marcaida, an employee at the Chestnut Street Gap, started working for the company at the flagship store 21 years ago. She wears all Gap and loves the brand but acknowledges the ups and downs. “I’ve seen a lot of change over the years with how they run the company,” she said.

Historically, Gap delivered an idea. It sold the timeless appeal of khakis. It sold pocket tees thanks to sharp black-and-white photographs by Annie Leibovitz and Herb Ritts. It sold folding—those neat piles of shirts in the cluttered chaos of a mall.

What is Gap selling now?

Maybe it’s not too late for Gap to reinvent itself, or go back to doing what it did best—a store with only jeans and records sounds like it would fit right in on the Valencia Street of today.

In the Chestnut Street Gap, a young store clerk named Crystal Lepe, whose first ever jean jacket came from the brand, works alongside Betty Agnos, an 82-year-old shopper who appreciates the clothing as “affordable and modern, a good all-around store for all people.”

The funk hip-hop group Winston Surfshirt is blasting, and for a fleeting moment, this San Franciscan imagines there’s still a way for Gap to stitch itself back together.