Janice Li’s re-election is shaping up to be an easy one: she’s running unopposed to keep her BART board seat (opens in new tab), representing part of San Francisco in the regional transit authority.

The real challenge she faces has less to do with her campaign than in getting her Chinese name to appear on the ballot.

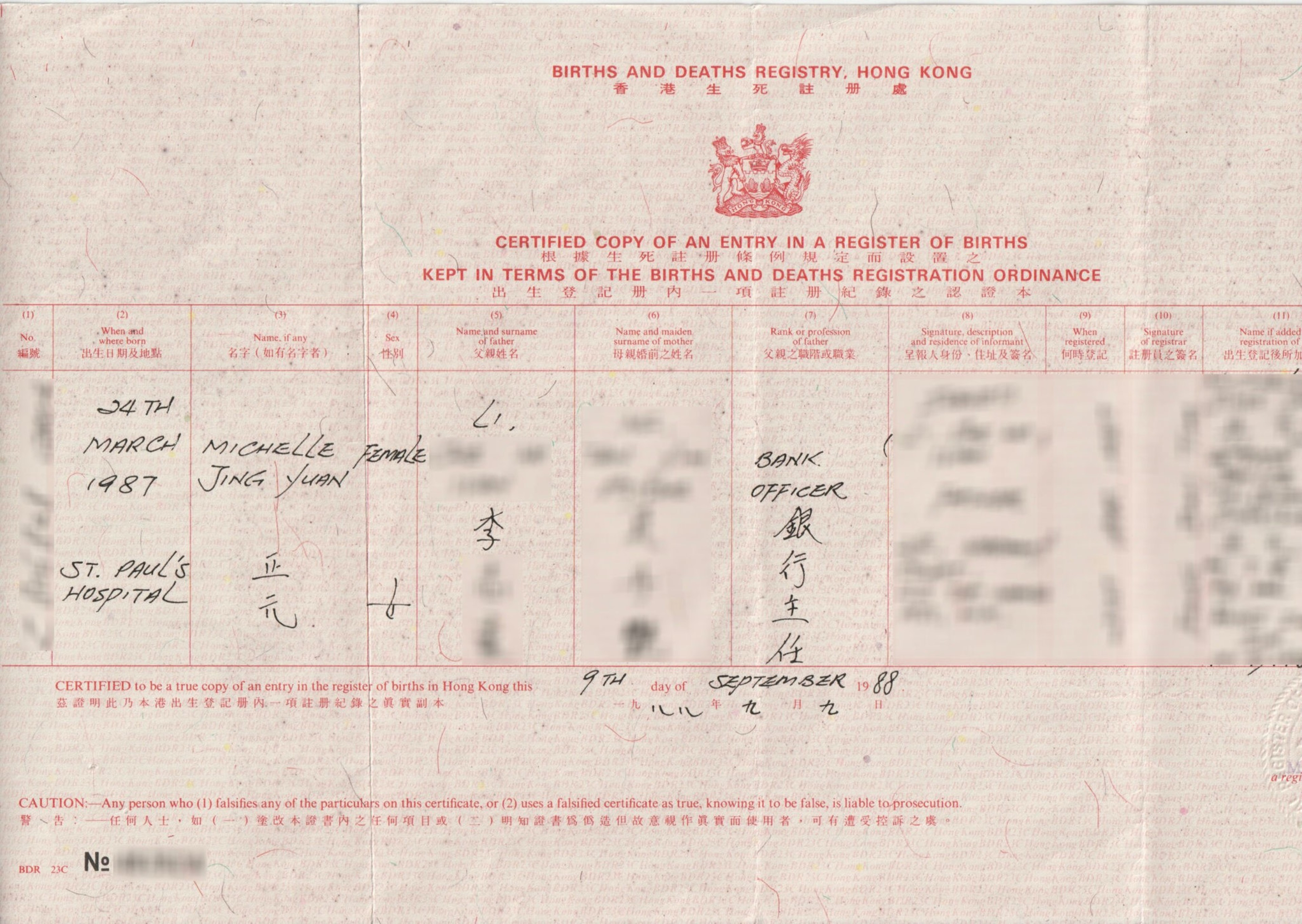

It started at the San Francisco Department of Elections—“I triple-checked all of the paperwork I needed to bring,” Li recounts—and turned into an intercontinental saga, one that had Li unearth the original birth certificate from her native Hong Kong.

To Li, it was important for her Chinese heritage to show through, regardless of whether her political race was competitive. Some Chinese voters may not know any candidates at all, and just vote based on name alone. They might wonder, Li said, “Does it sound Asian? Does it sound ethnically one thing or another?”

About 184,000 Chinese people live in San Francisco, or 21% of the city’s population, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Of that population, 118,000 are foreign-born and a large share of them speak Cantonese and Mandarin.

Not all can vote, of course. But their large presence gives them considerable sway over local politics.

Because of the city’s robust Chinese-speaking population, San Francisco ballots are, by default, bilingual in English and Chinese. That means every candidate’s name—whether they’re of Chinese ancestry or not—appears in English and Chinese, too.

With Asian American identity politics playing heavily into local politics, it’s become a city tradition for candidates to get a Chinese name on the ballot.

Years ago, the city used to let candidates pick their own Chinese names, which led to local figures adopting ballot monikers that translated to, in State Sen. Scott Weiner’s case, for example, something to the effect of “bold, majestic, charitable and tall. (opens in new tab)” Otherwise, the Department of Elections has hired a contractor to provide direct transliterations.

On the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, only two supes are Chinese Americans born with a Chinese name—but their nine non-Chinese colleagues each have a Chinese name of their own on the ballot.

Supervisor Aaron Peskin’s, for example, is listed as 佩斯金. Supervisor Catherine Stefani appears as 司嘉怡. Mayor London Breed’s Chinese name is also a direct transliteration.

For pretty much everyone in San Francisco politics—from District Attorney Brooke Jenkins, Public Defender Mano Raju, Treasurer Jose Cisneros and Assessor-Recorder Joaquin Torres, to the local school district and city college board members—having a Chinese name is a matter of course.

One might think the process would be straightforward for a candidate of Chinese ancestry. In Li’s case, however, it was a little less so.

Rules of the Name

In 2019, Assemblymember Evan Low, D-Campbell, who’s also Chinese American, authored AB 57 (opens in new tab) to regulate the Chinese translation on the ballot. AB 57, which passed into law, states that, with the exception of being born with the name or using it for at least two years, a candidate can only use a Chinese name on the ballot based on transliteration.

Unlike four years ago, when Li filed to run for re-election this time, she knew she had to prove her birth name. The rule sent Li on a hunt for the birth certificate issued in 1987 by the Birth and Deaths Registry under British colonial rule in Hong Kong.

Thankfully, she had it on hand after her family helped dig it up to prove that she was indeed born with the name 李正元, Jing Yuan Li, and had every right to present herself that way to voters.

“I use it, it’s what my parents called me,” Li said, “which is very different from someone with the ability to create a name that makes them look powerful on a ballot.”

Apparently, there’s more than one way to prove one’s right to a Chinese name in San Francisco.

In local races, the city’s Department of Elections has rules (opens in new tab) that slightly differ from those spelled out under Low’s AB 57. John Arntz, who helms the department, said they accept many sources to verify the Chinese names: “newspaper articles, videos from news outlets mentioning a candidate and even previous campaign flyers and related materials.”

In 2019, then-supervisor candidate Dean Preston requested his Chinese name to be 潘正義, which means Justice Pan, and got rejected (opens in new tab) by the Department of Elections because the name came off as giving a positive spin, which is considered unfair to other contenders. Even so, Preston won the election and has gone by Justice Pan on the ballot and in the Chinese press ever since.

Because he’s used it for a while and it’s been widely publicized, San Francisco election officials grandfathered him in, and let him use it on the 2020 ballot.

Arntz insisted that AB 57 doesn’t apply to San Francisco local races because the local election code already has guidance on Chinese names without the two-year requirement. However, Low’s office stated that “AB 57 applies to any jurisdiction if they currently provide a translation of the candidates’ name.”

The City Attorney’s Office tells The Standard that it’s currently reviewing AB 57 and its impact on local races.

Li said the two-year-usage requirement might make it hard for non-Chinese political newcomers to establish Chinese names compared to established elected officials. But she supports the state law imposing it after seeing the power of her birth certificate proving her own identity.

“Some people are criticizing me for either being a fake Asian or not really representing Chinese people,” Li said. “But the truth is that I was born in Hong Kong, and I am ethnically Chinese.”