Gallery of 5 photos

the slideshow

Strolling down Shotwell Street in the Mission, Reggie Lichtner’s house is impossible to miss.

The front yard of the otherwise modest Victorian sports dozens of large, hand-made wooden figures, an eclectic festival of bright colors and sharp angles. Some are whimsical, some are political, but all were crafted with his kids in mind.

Lichtner, 59, has created hundreds of sculptures over the past three years—all while immigration paperwork and COVID-19 travel restrictions kept him separated from his wife and children. The art, Lichtner says, kept him sane during the years apart.

The dad of two has lived at the home on Shotwell Street twice in his life: First, during young adulthood, when his only dream was to “make it” as a musician, and next when he returned to San Francisco in 2018 to take care of his ailing father.

In between, Lichtner had been building houses—and a family—in Panama. It’s there that he met his wife, Iris, and had two kids, Lily and Kyle.

When Lichtner went to San Francisco to look after his father, the plan was for Iris and the kids to join shortly thereafter. Lichtner and the children are U.S. citizens, so the family assumed Iris’ visa would take just a few months to process.

It didn’t work out that way.

Instead, immigration bureaucracy–and later the pandemic–kept the family apart for almost three years.

“COVID-19 was an afterthought,” Lichtner said. “What stressed me out was: ‘Are they ever even going to let my family into America?’ I realized—my kids were growing up without me.”

Gallery of 1 photos

the slideshow

To distract himself, Lichtner poured his soul into renovating the old San Francisco-style home.

By the end of the first year apart, the outdoor deck was expanded, the kids’ rooms had lofts and the house was in great shape. But Lichtner realized he needed to stay busy to “keep out of trouble.”

So he built himself a place to create in the backyard and told himself: “You have permission to do shit art. You’re gonna do shit art. But do it with a sense of wonder.”

And do it, he said to himself, for your kids. Much of Lichtner’s work reflects his longing for his family. He credits art for enabling him to process his separation from his family, Trump’s presidency and the murder of George Floyd.

With the woodworking skills of a carpenter and the creative mind of a musician, Lichtner also went from lonely caretaker to neighborhood icon in those three years, with local artists noticing his work as it poured out of the house and into the yard.

Renée DeCarlo, who owns The Drawing Room gallery on 23rd and Mission streets, said she brought her art students by Lichtner’s house regularly, before ever meeting him, to view and discuss “history in the making.”

DeCarlo had assumed the works were created by various artists due to the varied nature of Lichtner’s sculptures. She described his practice of public art display to her students as “incredibly courageous.”

When Lichtner accidentally stumbled into DeCarlo’s gallery during an exhibition opening, she says she literally jumped with joy upon discovering he’d single-handedly created the sculpture garden on Shotwell Street.

“I think it’s humbling to meet people like that, who have so much [talent] to give and share,” she said.

Lichtner’s art is worked into the earth it grows from: The natural landscape is necessary for many of the pieces. Working with wood, Lichtner says, grounds his art—both literally and figuratively.

The art doesn’t stop once you reach the front door of the two-story home. Every square inch of the interior is filled with Lichtner’s pieces. They crawl up the walls of the bedrooms and spill into the backyard.

Though the inspiration behind some of Lichtner’s sculptures might be rated ‘R’ by more conservative parents—like the swirly, trippy piece titled “Orgy” above the kitchen sink—most of the works available for public viewing are something from a kid’s whimsical imaginary world.

“I try to be edgy,” Lichtner says. The artist is consistently “trying to find the line right before something goes over into ugly or not working. There’s a point right before, where it’s kind of alive.”

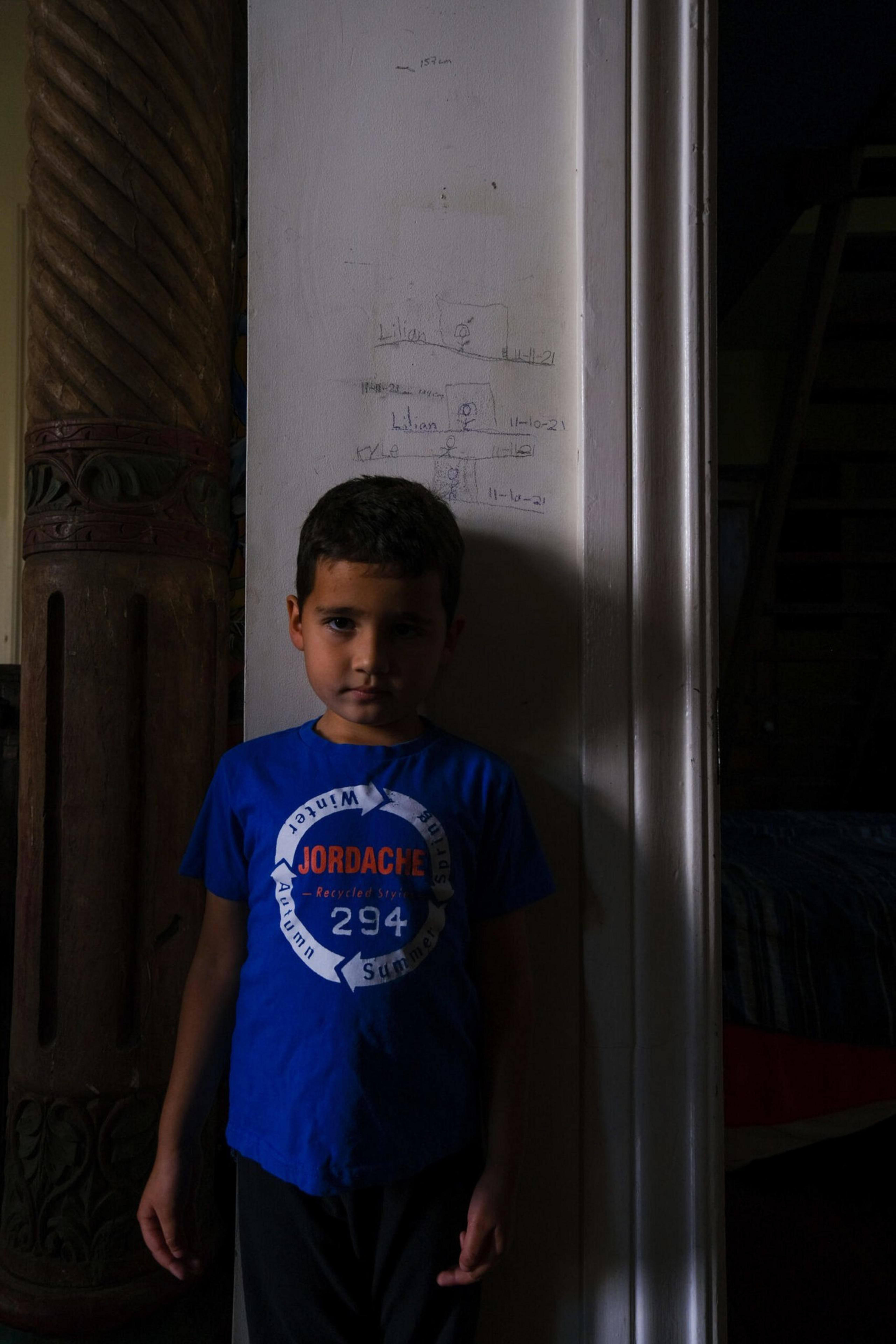

Today Lichtner’s family is back together again. Iris’ visa was granted in 2021.

They traveled for two full days in May of 2021 to get to San Francisco from the small Panamanian town where the kids had lived their entire young lives. The family arrived in the dark in a taxi—exhausted but thrilled—and woke up to a garden of 10-foot-tall sculptures and a house full of Lichtner’s hopes, fears and dreams.

Nowadays, Lichtner doesn’t just create art for his children—but also with them. Outside, he shares his workshop with his kids, building and crafting together like no time has passed.

Lily, 7, says she wants to be an artist when she grows up, just like her father. Kyle, 5, says he’s still figuring it out. Lichtner, too, is still figuring it out—how to be a family after so many days apart and how to help his wife and children adapt to a new home and country.

Though the drama of the past few years has made Lichtner doubtful of “The American Dream,” he still spends most of his days building his family’s personal dreamland, right at home in San Francisco.