A San Francisco sheriff’s deputy who was reinstated after the city attempted to fire him three times was the city’s highest-paid employee last fiscal year, making over $726,000—including regular compensation and years of back pay.

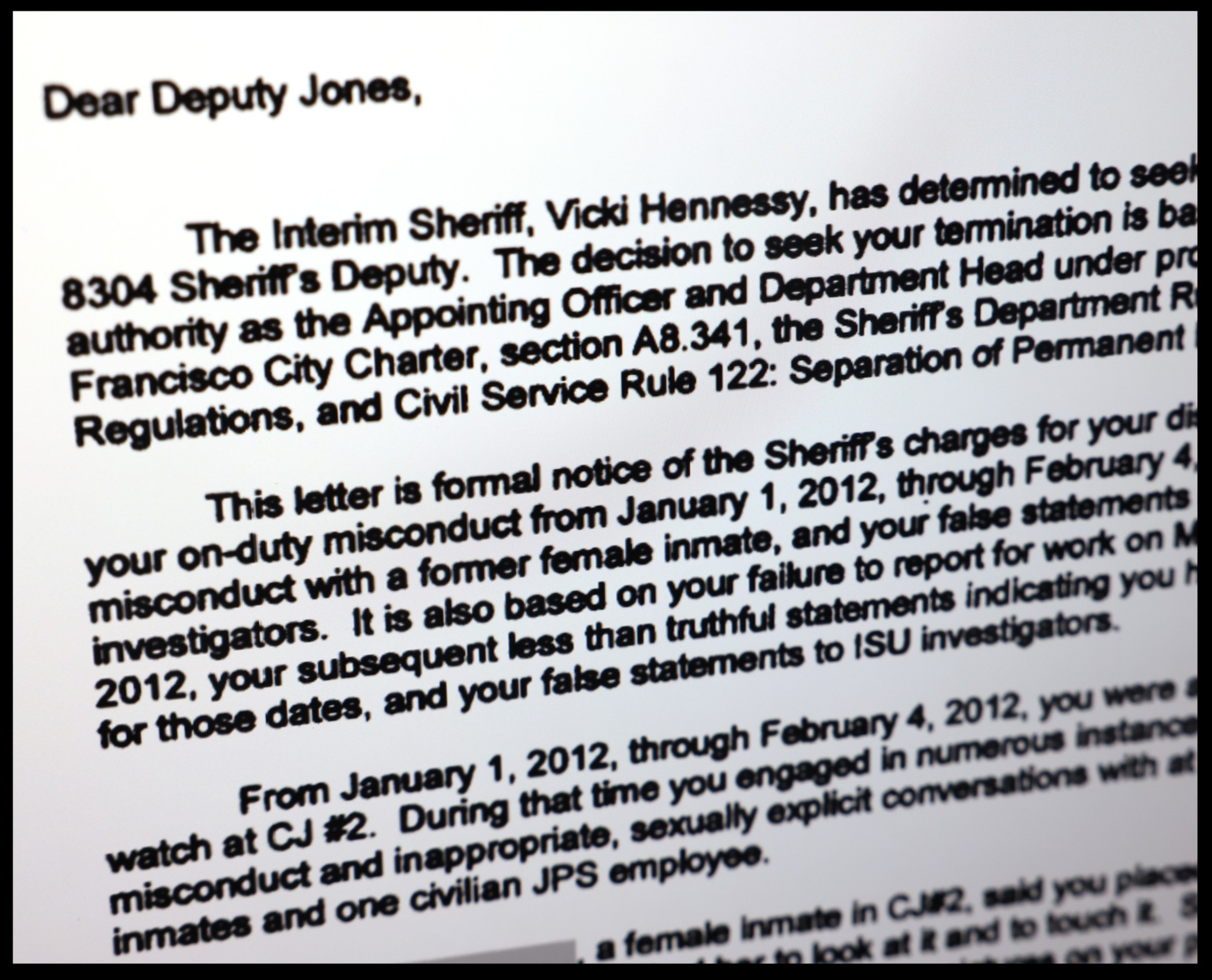

Douglas Jones initially received two termination letters in 2012 and 2013 after multiple female inmates and an employee in the jail accused him of repeated sexual misconduct, including asking female inmates to touch his penis, making sexual remarks while watching inmates shower and sharing naked pictures of himself and others.

After both of those termination letters, the department reached a settlement to reduce Jones’ firings to a suspension and reinstate him. But after a third firing for reasons the department refused to disclose, former Sheriff Vicki Hennessy disputed an arbitrator’s decision to reduce the discipline. That led to a lengthy court battle in which Jones won his job back along with $705,721 in total back pay and 854 accrued vacation hours for time that he wasn’t working between 2015 and 2020.

The annual base salary for a deputy sheriff in San Francisco ranges between $84,448 and $130,936, according to the department’s website (opens in new tab).

The saga of Jones’ firing and eventual reinstatement illustrates how third-party arbitrators can supersede a department’s decision to terminate an employee and win them back pay at great taxpayer expense, even in cases with serious allegations. According to some law enforcement experts, that process can also result in placing problematic employees back in positions of power.

Jones’ attorney, Harry Stern, told The Standard in an email that the charges against Jones were disproved and that he was the victim of a number of retaliatory information leaks.

In a letter to the department in 2012, Stern argued that the sexual misconduct allegations against his client were orchestrated by a group of inmates with ulterior motives. In subsequent emails, Stern said that the 2015 firing had put Jones in dire financial straits, forcing him to borrow money to support his family.

Jones is the son of Zula Jones, a former member of the city’s Human Rights Commission who pleaded no contest to bribery charges in 2019 (opens in new tab). The Sheriff’s Department declined to answer questions about Douglas Jones’ current role in the city’s jail. The San Francisco Deputy Sheriffs’ Association also declined to comment on the case.

People who worked with Jones told The Standard they were appalled by his reinstatement.

“It’s the good ol’ boys club. They do bad things, and then they back each other up,” said Toni Tombari, a former forensic therapist (opens in new tab) in San Francisco’s jail. “There’s not only no repercussions or consequences, but oftentimes, there’s some type of reward.”

Abuse of Power?

Tombari said Jones worked security at the front door when she worked at the jail. She accused him of making inappropriate comments about her body.

Tombari left her job in San Francisco’s jails in 2012, saying she was disturbed by power dynamics that enable the exploitation of inmates.

“This is not some isolated incident,” Tombari said. “These things happen all the time, and the deputies rely on abusing their power.”

Tombari said that her colleagues complained Jones had sent them naked pictures and sexually harassed them, echoing the allegations detailed in a 2012 document seeking Jones’ dismissal.

In that document, then-interim Sheriff Hennessy said Jones’ alleged actions constituted criminal conduct and caused embarrassment for the department.

The document describes a slew of testimonies made against Jones by inmates, who contended that he preyed on women in the shower, asked them to touch his genitals and touched a female inmate’s breasts without her consent.

As he awaited a hearing on the 2012 termination letter, Jones allegedly violated an order not to contact any victims or witnesses in the case, leading then-Sheriff Ross Mirkarimi to serve him with another termination letter in 2013.

That case was settled through a six-month suspension without pay, following a 30-day suspension that Jones served for undisclosed reasons in 2011.

But then in 2015, Hennessy fired Jones a third time for reasons that haven’t been released to the public.

Some of the city’s other top-paid employees last fiscal year included: Kurt Braitberg, the managing director of the city’s retirement system; Sheriff’s Lieutenant Ronald Terry; and Department of Public Health Director Grant Colfax. Braitberg was the second highest-paid employee in the city after Jones, collecting $707,505. Meanwhile, Terry made $678,933, and Colfax collected $646,768.

Legal Saga

After Jones was fired in 2015, an independent arbitrator reduced his discipline to a written reprimand and ordered that he be reinstated and reimbursed for lost wages and salary.

Hennessy, the sheriff at the time, rejected the appeal and cited a clause in the department’s collective bargaining agreement that allowed her to ignore the arbitrator’s opinion.

Jones, represented by the sheriff’s union, argued that the allegations were untrue and sued the Sheriff’s Department for violating labor laws by dismissing the opinion of the arbitrator.

Hennessy argued the department’s collective bargaining agreement gave her authority beyond the decision of the arbitrator. But the department hadn’t cited that agreement when it initially fired Jones—a policy discrepancy that led to his successful appeal of the department’s decision in court.

Jones officially rejoined the department as a deputy in November 2020.

John Alden, a longtime Bay Area law enforcement watchdog, told The Standard that the case illustrates how arbitrators can make the wrong decision because they’re overly committed to finding a compromise. Alden said he found it notable that Sheriffs Mirkarimi and Hennessy, who were often on opposite sides of issues, had both tried to fire Jones.

“Arbitrators are literally there to resolve disputes; they’re not necessarily experts about misconduct,” Alden said. “Someone who doesn’t even work for San Francisco gets to make a decision that puts a sheriff’s deputy back to work? How’s the public supposed to feel about that?”

One inmate alleged that Jones met with her outside of jail after she was released and took her to a gun range. At one point, she alleged, Jones asked her where he could buy crack cocaine, according to the termination document.

Margo Frasier, a former Texas sheriff and current criminal justice consultant, said the discrepancy between the department’s decision and the arbitrator’s decision demonstrates the risks of involving a third party in disciplinary cases.

Third-party arbitrators are used as a way to protect employees from being excessively disciplined, Frasier said. But they aren’t required to be trained legal experts and often feel compelled to reduce disciplinary action.

“Two sheriffs felt that they were correct in terminating this guy,” she said. “How can you in good faith put him back in contact with inmates?”