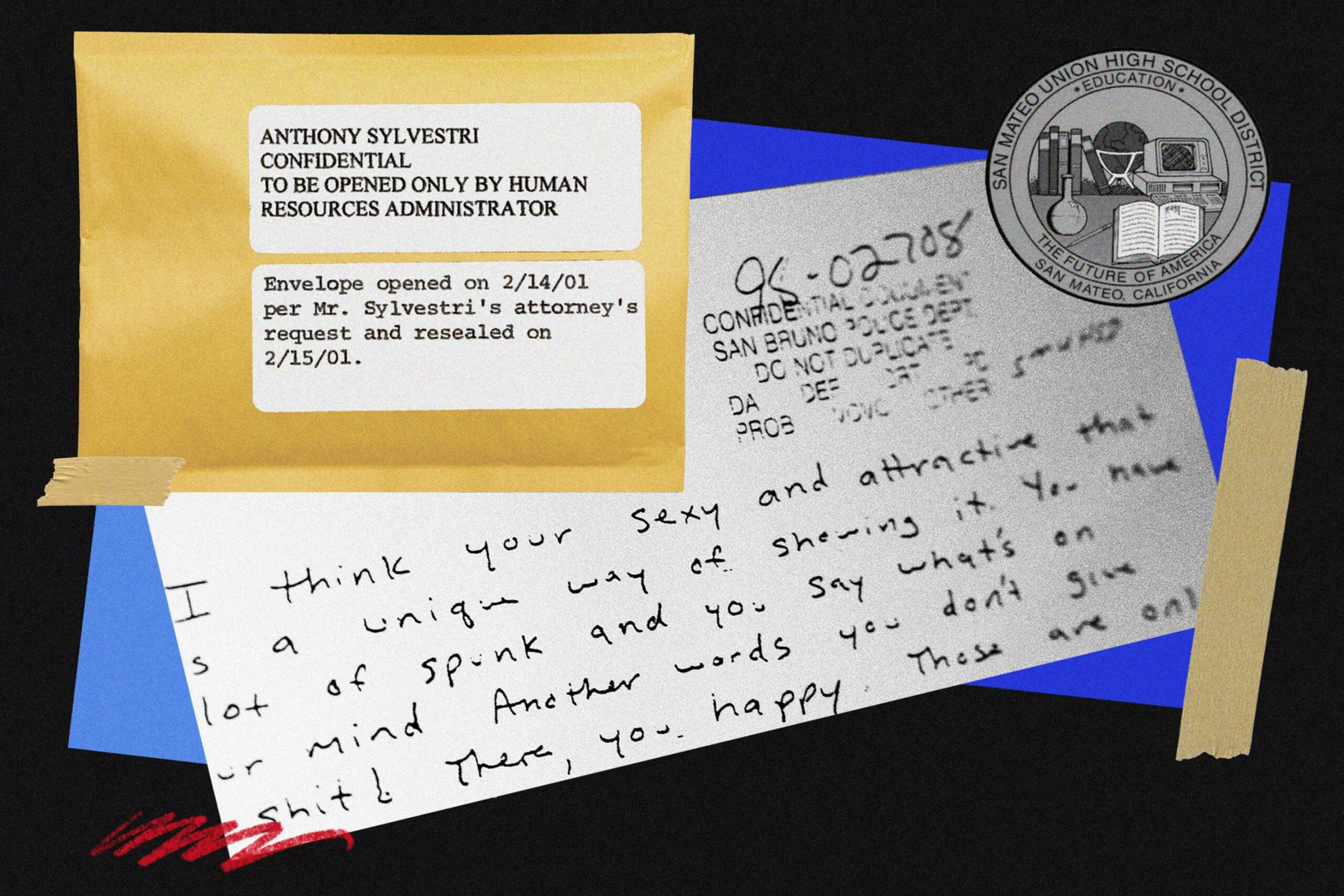

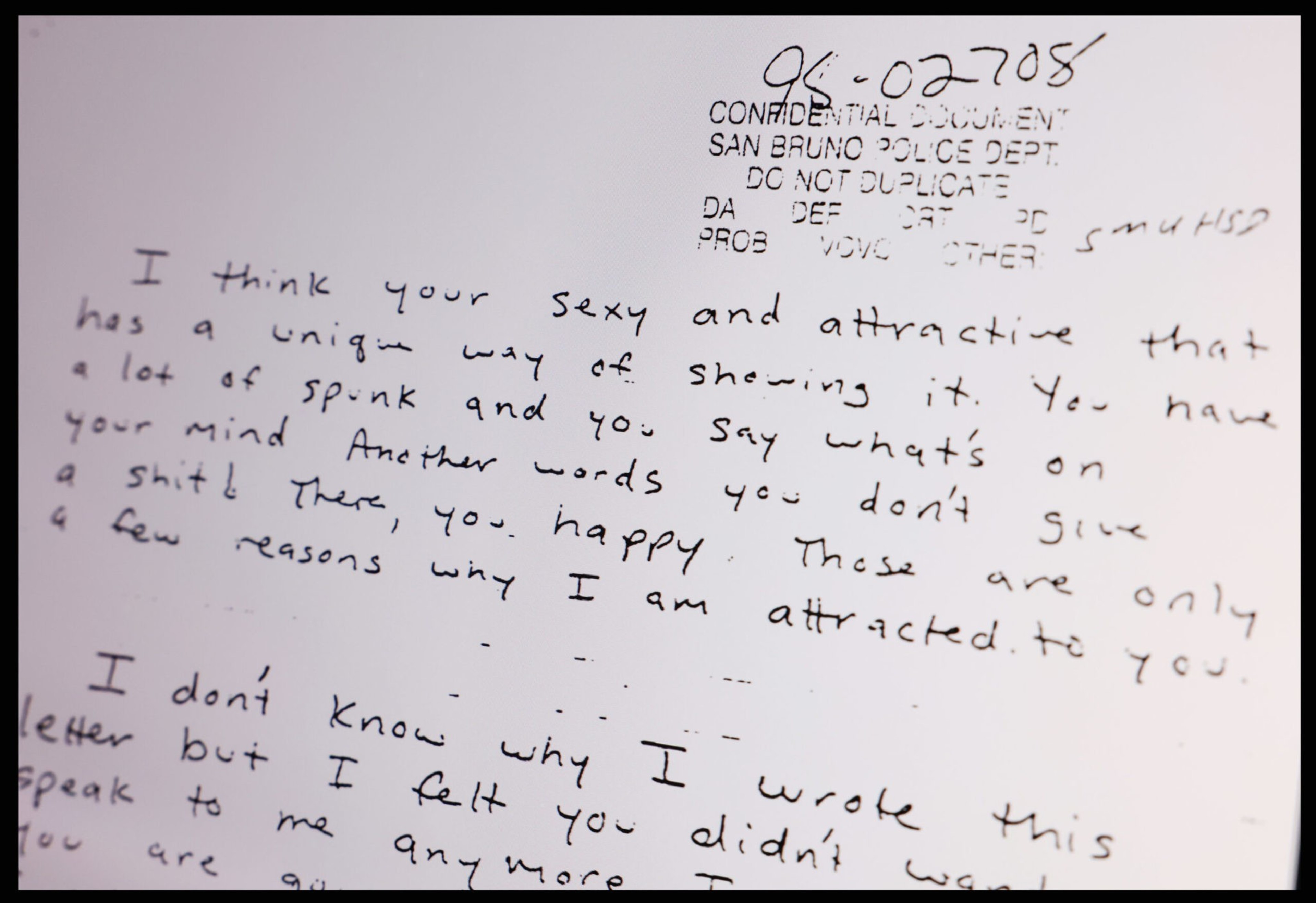

As police investigated explosive rumors about a Bay Area educator allegedly having sex with several students in 1998, they were handed a letter in which he described a student as “sexy and attractive.”

“I’ve told you how I feel about you and you know what I like,” physical education teacher Anthony Sylvestri wrote to a student at Capuchino High School in San Bruno. “I may tease you a little bit and you tease me sometimes but I think that’s alright.”

The letter built upon other evidence that police and administrators compiled as they investigated whether Sylvestri had been inappropriate with girls at the school. They heard allegations that he had peppered several students with personal phone calls, kissed the girl he wrote the letter to, and made multiple comments to girls about the size of their breasts, their weight and their overall appearances.

San Bruno police, in their report to the district attorney at the time, said no crime had been committed, that rumors he had sex with 12 students were just rumors, and that those interactions that Sylvestri did have with girls had been “agreed upon by both parties.” Sylvestri was allowed to resign and receive a semester’s pay, and the administration agreed not to tell inquiring potential employers why he had left the San Mateo County school.

In 1999, Sylvestri was hired by Aptos Middle School in San Francisco. There, two decades later, administrators would hear claims from students that he made them uncomfortable by calling them pet names, leering at them and touching them for no clear reason.

During the course of the San Francisco school district’s investigation into allegations against Sylvestri, a former Capuchino student submitted a declaration that the teacher had kissed her on the mouth and groped her breasts and body at least three times during her senior year, The Standard reported.

In 2019, after two investigations by San Francisco school officials, Sylvestri was ultimately allowed to resign from Aptos in lieu of facing disciplinary hearings.

In total, it took four rounds of student complaints and administrative investigations, in two school districts, over 20 years, for Sylvestri to finally lose his teaching credential in 2021.

There was no evidence he was ever charged in related criminal cases. Sylvestri did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Sylvestri was one of 19 employees accused of sexual misconduct whom San Francisco schools have allowed to sign resignation agreements since 2017, The Standard revealed last month.

Despite dramatic changes in law and policy since 1998, consultants, attorneys and advocates who specialize in sexual misconduct against students told The Standard that these anachronistic attitudes and behaviors persist in today’s public school systems and law enforcement agencies.

They said that school administrators sometimes remain protective of teachers, can be loath to find students credible and are at times eager to protect themselves from damaging publicity.

Commenting on the handling of Sylvestri’s cases, Laura Palumbo, spokesperson for the National Sexual Violence Resource Center said, “If you told me they were from the past year, that would be believable to me.”

Sandra Hodgin, a consultant to schools and law firms on student harassment issues, reviewed the San Bruno police and school records at The Standard’s request.

“Looking at this 1990s case, and cases today, the cases are so similar to what I see on a regular basis,” she said of the documents, which were obtained through a public records request.

‘Skepticism Throughout’

Police and the school district in San Bruno concluded that most of the students’ claims about Sylvestri in the 1990s were not true. They found that some rumors were partially motivated by conflicts between girls at the school who may have considered the teacher, then in his late 20s, to be cute. And students’ stories shifted at times.

However, documents related to the San Bruno investigation into allegations in 1998, and another previous San Bruno school investigation into rumors about Sylvestri in 1996, suggest that the school officials and police may also have overlooked or downplayed serious warning signs.

In 1996, school officials found Sylvestri had made calls to four girls and attempted to meet up with them outside of school. They concluded that Sylvestri “had used some poor judgment, but no improprieties had taken place.”

School officials “warned him that any social contact or suggestive behavior towards students was totally unacceptable, and that he must go out of his way to prevent rumors from getting started,” according to a letter from the school’s principal to the assistant district superintendent.

Sylvestri denied any improprieties with female students and agreed to be more careful in the future, the letter noted.

Two years later, during the second investigation, the police got involved. In their 1998 report, they wrote that Sylvestri admitted to kissing a girl, but “only in a friendly way.”

Even after police received the letter, which Sylvestri later admitted to writing, they concluded that it “did not have any sexual content.”

Neither the San Mateo Union High School District nor the San Bruno Police Department responded to requests for comment.

“That skepticism that’s throughout this file, of the girls saying there were 12 students he slept with—I think today, we’re far less skeptical. We’ve seen quite a history of predatory teachers and other school employees,” Brett Sokolow, a Los Angeles consultant who advises schools on anti-harassment policies, said, speaking generally. “There’s a skepticism that means you’re not going to take the investigation as far as you might otherwise, [that] if we pursue this it would ruin the reputation of a valuable member of our community.”

Experts say that even after the sexual assault convictions of Bill Cosby and Harvey Weinstein and the rise of the #MeToo movement, schools still have a long way to go.

Emma Grasso Levine, a manager with the nonprofit Advocates for Youth, still sees institutions prioritizing liability and reputation over the concerns and wellbeing of students who have experienced sexual harassment and assault. That includes victim-blaming, minimizing allegations and failing to consider power dynamics.

“It makes it easier for adults to minimize or hide the fact,” she said, “as opposed to engaging in a meaningful accountability process.”

There have been substantial changes in the law since 1998, as California statutes have been amended to address sexual harassment of children. The federal Department of Education began issuing revised guidelines on preventing sexual harassment during that time period.

And today, “we know what targeting and grooming look like. I think there’s far more willingness to believe the rumors, to believe students. We have more sophisticated investigations,” said Sokolow.

Notwithstanding, Billie-Jo Grant, a member of the board of directors of Stop Educator Sexual Abuse, Misconduct and Exploitation, said some administrators’ attitudes lag behind the times.

“Many still believe it will never happen on their campus,” she said.