Two dozen of San Francisco’s top YIMBYs gathered in a spacious Bernal Heights backyard in September to discuss the movement founder’s latest venture: a $1 million cash reserve to take San Francisco to court should it stymie any new housing projects.

YIMBY founder Sonja Trauss, who led a group discussion about the annals of housing policy while soothing her newborn baby, likened the Sue San Francisco Fund to a denial-of-service (DoS) attack on the city, referring to a type of cyber strike that paralyzes its target by blitzing it with an overwhelming number of requests.

“The denial-of-service portion is because we could send threatening letters for every single missed housing deadline,” Trauss said, describing the money as ready-to-go ammunition to sue San Francisco over housing deadlock.

The crowd of mostly male tech workers—the “hoodie caucus (opens in new tab),” in the words of one industry observer—rippled with excitement. This was a problem that could be solved with software and automation, which was squarely in their domain.

“We could make it so that every time the city does something out of compliance, we automatically generate a lawsuit letter, kind of like DoNotPay,” offered one sandals-clad engineer, referring to a website that calls itself “the world’s first robot lawyer.”

For the rest of the evening, the group nerded out on one arcane housing acronym to the next. The mood was celebratory.

YIMBYs—the “yes in my backyard” housing boosters—have reason to be optimistic.

To borrow a phrase from tech, their cause has been in hyper-growth mode. In about a decade, Trauss went from a lone dissenter facing off against neighborhood activists in San Francisco Planning Commission meetings to the figurehead for a sprawling movement with 140 groups in 29 states (opens in new tab) that goes toe-to-toe with local politicians and homeowners over housing construction.

But on their home turf, YIMBYs have watched their goals slip seemingly further and further out of reach. Last year, the city authorized 43% fewer units (opens in new tab) than its 10-year average. The Board of Supervisors has recently thwarted projects like a high-rise on an empty parking lot, drawing protests. In comparison, California as a whole has nearly tripled the number of annual housing permits issued in the last decade, according to the Census Bureau.

The San Francisco YIMBYs—many of whom are tech founders who got rich from thinking big—are fed up with incrementalism.

Forget trudging to City Hall to kiss politicians’ rings or sparring with neighborhood activists at planning meetings. YIMBYs and developers now believe that public support for housing, wealthy donors and state backing have created a perfect storm that will allow the building process to circumvent San Francisco city government entirely.

First up is Proposition D on the November ballot, where San Francisco voters will decide whether to streamline the construction of certain apartment projects, both affordable and market-rate. YIMBYs and their allies gathered signatures for the measure after the Board of Supervisors twice prevented Mayor London Breed’s attempt to get it passed. In a testament to their political might, the campaign has raised over $2.3 million (opens in new tab) so far.

Birth of a Movement—and Its Critics

Nowadays, San Francisco may be better known for its tech companies than political activism. But it was the city’s tech boom that laid the groundwork for what has become an unusually successful activist movement.

A YIMBY writ large is a person who believes that rising rents, homelessness and inequality could be solved if cities allow for denser housing. The San Francisco of the past decade—when rising rents collided with fewer homes getting built—catalyzed the yes-in-my-backyard movement.

In the eyes of many locals, the skyrocketing startup sector was to blame for the housing crisis: Techies were clogging their neighborhoods, driving up rents and turning the city into a gentrifying playground for the rich. Protestors vomited on a Yahoo corporate shuttle (opens in new tab), as graffiti reading “Die techie scum” sprouted in the Mission District. Many believed that the housing market had become so out of whack that there was no way new market-rate housing could be affordable.

Ten years ago, Trauss was new to the Bay Area and struggling to afford rent. But she saw the housing issues differently.

She had just come from St. Louis and Philadelphia, two places that didn’t have enough jobs, and she had seen what too few jobs did to a city.

“It was just so unbelievable for people to be like, ‘Our big civic issue is too many jobs,’” she said. “The problem was too little housing.”

The real culprit, she said? It was NIMBYs—an acronym for “not in my backyard,” or neighbors who oppose housing construction—often the loudest voices in the room when city officials decided whether to approve new housing projects, according to Trauss.

So in 2014, Trauss decided to take a day off work to go to San Francisco City Hall to counteract the NIMBYs, according to Golden Gates, a book documenting the rise of YIMBY. A few months later, she convinced a group of fellow millennials to speak in favor of housing developments, garnering coverage in the likes of The San Francisco Examiner, Vox and Bloomberg. By the year’s end, Yelp CEO Jeremy Stoppelman gave Trauss $10,000, enabling her to quit her teaching job to become a full-time activist.

Over the next several years, Trauss’ activism evolved from City Hall gadfly-ism into real political clout. Laura Foote, a political organizer, joined forces with Trauss and assembled a foot army that helped then-Supervisor Scott Wiener get elected to the state Senate.

Foote said a lot of the movement’s organizational success revolved around fostering a community who clearly understood the organization’s goals, and then empowering them through a decentralized management structure. For example, the organization has 35 volunteer leads who don’t need approval from an official employee to carry out important tasks like sending out newsletters.

But there were major bumps in the road. In 2018, the YIMBYs ran a failed ballot initiative (opens in new tab) to streamline certain types of construction. Trauss ran to represent the SoMa district on the Board of Supervisors and got trounced by Matt Haney, who was then firmly aligned with the city’s progressive political faction. Once equating a lack of desire to build housing in the Mission to xenophobia, Trauss herself really pissed people off.

Since then, political winds have shifted dramatically: As San Francisco’s Downtown emptied out during Covid, the anti-tech narrative lost steam.

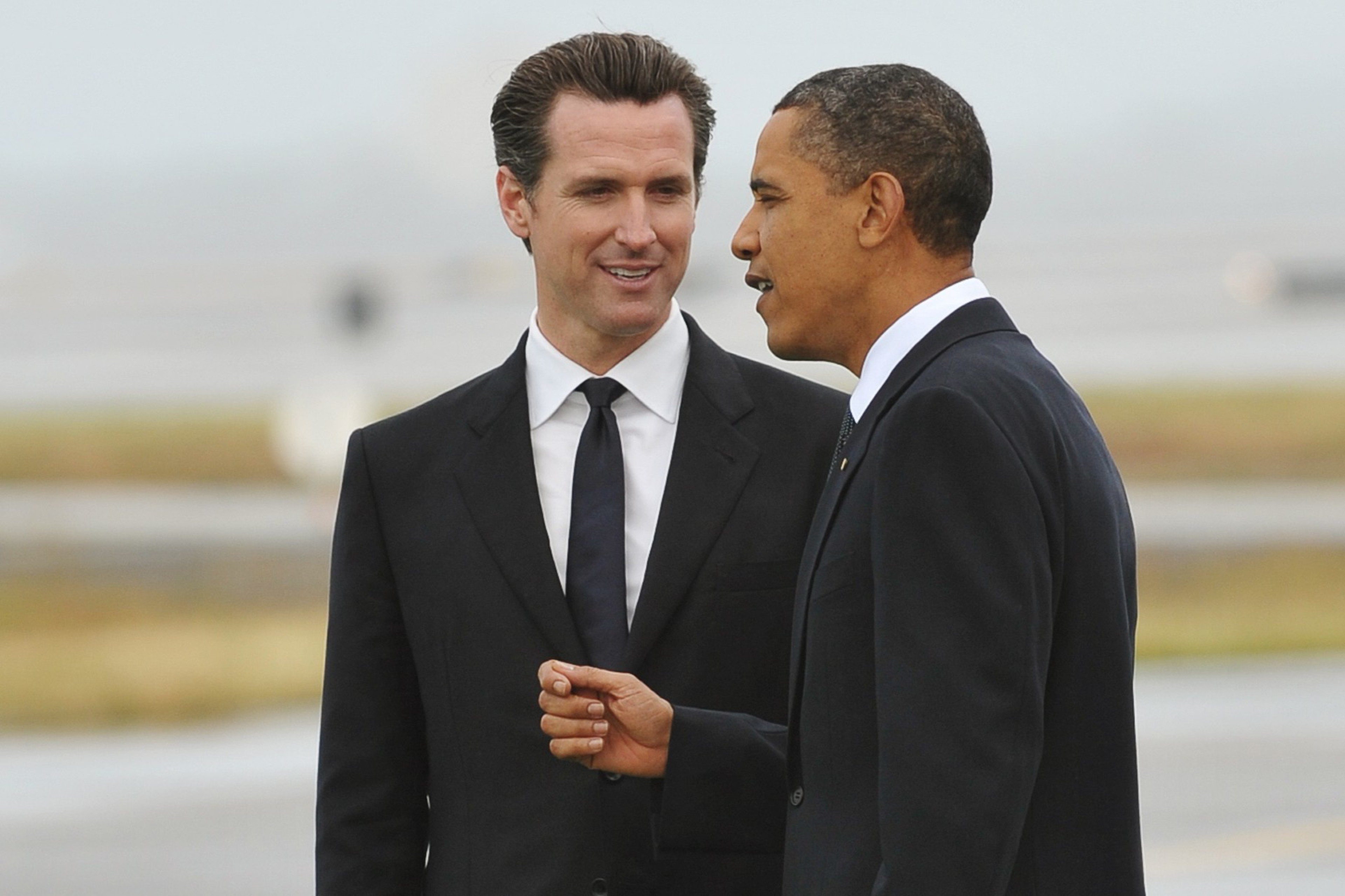

Today, politicians ranging from Gov. Gavin Newsom and former President Barack Obama to current President Joe Biden have made more housing a key initiative. And the movement succeeded in turning “NIMBY” into a derogatory term for selfish homeowners—often in wealthy communities—who don’t want new buildings, let alone people, in their backyards.

New pro-housing groups are forming at a strong clip, according to a recent Brookings Institute study (opens in new tab). Of the 140 identified, 24 were in the Bay Area—the biggest and oldest of which is San Francisco-based YIMBY Action, with 10 full-time staff, nearly 2,500 dues-paying members and many more non-dues-paying members. Another group, the statewide California YIMBY, boasts 15 full-time staffers and 80,000 members after only five years in existence. California YIMBY has sponsored 17 statewide bills, which have been key in weakening local officials’ ability to block construction.

Stymied in San Francisco

Despite the momentum in recent years, San Francisco’s politicians have failed to authorize more housing.

A year ago, San Francisco politicians rejected a 495-unit high-rise in SoMa that was to be built on a parking lot, citing shadows and concern about gentrification. Weeks before that, the same politicians unanimously rejected a 316-unit development in the Tenderloin—a project that was previously authorized by the Planning Department—over concerns that it would become a “tech dorm” (opens in new tab) instead of family housing.

Critics of the YIMBY movement say that they aren’t opposed to building housing, it’s that they believe the government needs to focus on getting below-market-rate housing built.

“It’s a fantasy that somehow more supply will start driving the price of housing down,” said Joseph Smooke, who in 2015 architected a failed ballot initiative to halt the construction of market-rate housing in the Mission, citing gentrification and displacement. “Could we embark on an accountable system for creating housing for people without relying on the market? Probably.”

Critics also contend that YIMBYism is just a convenient way for the real estate industry to rebrand itself. Walk into any local YIMBY meeting, and the majority of attendees will be people who can afford luxury condos: white, male tech workers.

“It’s beyond absurd that YIMBY—the very folks who are fine with demolishing people’s homes, evicting people and minimizing affordable housing mandates in our City—would accuse me of being ‘anti-housing’ … [YIMBYism] is not pro-housing, it is pro-developer, plain and simple,” said Supervisor Dean Preston, who regularly squabbles with YIMBYs on Twitter. He staunchly defends his housing record, citing his two decades as an eviction defense attorney and support of affordable housing.

Bigger, Bolder Plans

The YIMBYs have all but given up on arguing their side in Planning Commission meetings, instead setting their sights on bigger plans.

Among their current targets is a statute in the annals of California housing law, re-surfaced on Twitter (opens in new tab) by the UC Davis law professor Chris Elmendorf in 2019.

Called the “builder’s remedy,” the statute kicks in when cities don’t have a state-approved housing plan to accommodate projected population growth. At that point, cities are powerless to stop certain types of construction.

Before this year, utilization of the builder’s remedy had only been attempted once, in 1991, Elmendorf said. But as state housing targets ramp up, a Santa Monica developer recently submitted a plan to build 4,500 units using the builder’s remedy, (opens in new tab) which would be more housing than Santa Monica has built in the past decade. (A “stunned” Santa Monica councilmember called the plan “beyond the pale.” (opens in new tab))

San Francisco YIMBYs are already strategizing around the obscure law. If the city misses a key February deadline to get its housing plan, called the Housing Element, approved by the state, local developers may have a window early next year to bypass city government in one fell swoop.

“All we need is for a billionaire like Sam Altman to propose building a 100-story tower on his Russian Hill property and create 100 new affordable units,” said Barak Gila, a software developer whose side passion is YIMBY activism.

Builders increasingly don’t feel the need to play ball with city officials, Elmendorf said.

“There are now a variety of ways in which a developer does not need to rely on their close and possibly corrupt relations to build housing,” he said. “I’m hearing this anecdotally from lawyers who are saying they are starting to see developers who are moving towards ‘I’m going to stand on my rights’ and are comfortable going head-to-head with hostile city councils.”

NIMBY to YIMBY Pipeline

Ironically, it might be the case that soon YIMBYs won’t even need to circumvent local politicians. For up-and-coming politicians, running on a pro-housing platform is starting to look like table stakes.

Earlier this year, former Supervisor Matt Haney—who had opposed various housing initiatives earlier on—adopted a pro-housing stance to trounce his opponent in a race for an open state Assembly seat. The candidates shared virtually identical platforms except on housing, and many credited that for his victory (opens in new tab).

In the upcoming November election, candidates for city supervisor are beginning to follow suit. Sunset District representative Gordon Mar, who has been one of the loudest opponents of YIMBY legislation (opens in new tab) in the past, says his views have evolved. He pushed back against opposition to a 100% affordable (opens in new tab) building proposal in his district, and sought the local YIMBY endorsement (opens in new tab) for his campaign.

“I agree with the goal that they have, but I feel that their analysis is overly simplistic, especially the belief that continuing to overproduce luxury condos in San Francisco will somehow result in the housing that’s needed for families, essential workers and seniors,” he said.

Meanwhile in SoMa, where most of the city’s new housing is built, the top two candidates are competing to out-YIMBY each other.

For the YIMBYs, San Francisco’s housing gridlock had a silver lining attached, though: It gave their movement something to organize around.

“It makes people mad,” Trauss said. “It’s radicalizing, especially when San Francisco NIMBYs are unashamed and bold and making bad arguments.”