Oakland politicians have a simple playbook: When crime is rising, they wave it off (opens in new tab) as a broader state or national trend or blame it (opens in new tab) on the previous administration; when crime goes down, they take full credit (opens in new tab). Then they close with a virtuous spiel about violence prevention and policing alternatives as the future of a more just public safety system.

However, this playbook is not grounded in data about our streets or law enforcement. Oakland’s elected officials cherry-pick incomplete data (opens in new tab) that suit their political objectives, and much of the public accepts their spin at face value.

If the electeds did take a deep look, they’d find that the data were full of issues (opens in new tab) that could impair correct interpretation, because data gathering, management and curation are difficult and systemically underfunded. (opens in new tab)

Instead, they base public safety policy on political expediency, which in recent years has disrupted and dismantled the resources needed for fair and just policing.

Take the Oakland Police Department’s crime reporting system, which is more than 20 years old. It’s so degraded that the department can no longer use it to track investigation documents centrally. Instead, employees use Microsoft Word, save files on desktop folders and share them by email.

That system is supposed to automatically transfer uniform crime reporting data to the state for its annual crime compilation (opens in new tab). But that too is broken. The state recently released 2023 data (opens in new tab) showing 11,169 aggravated assaults in Oakland — a 3.4-fold increase over 2022. But OPD’s own report shows about 3,500 aggravated assaults (opens in new tab) in 2023. The state data are flawed because of an unresolved bug in transmission discovered a month ago.

Police sources say OPD is beta-testing a $12 million computer-aided dispatch system for 911 operations, funded by a state grant. The new system has a records module, but police can’t use it because it won’t communicate with the myriad of archaic OPD data and reporting systems required by local, federal and state oversight policies.

As record-keeping gets worse, it invokes a downward spiral. Trust plummets as a skeptical public demands transparency but does not get it. OPD is inundated with more than 10,000 public records requests (opens in new tab) each year, fulfilled by the same overtaxed workers — primarily the investigative staff of about 40 officers and administrators (excluding the homicide division), who are also tackling a caseload of more than 40,000 crimes (opens in new tab).

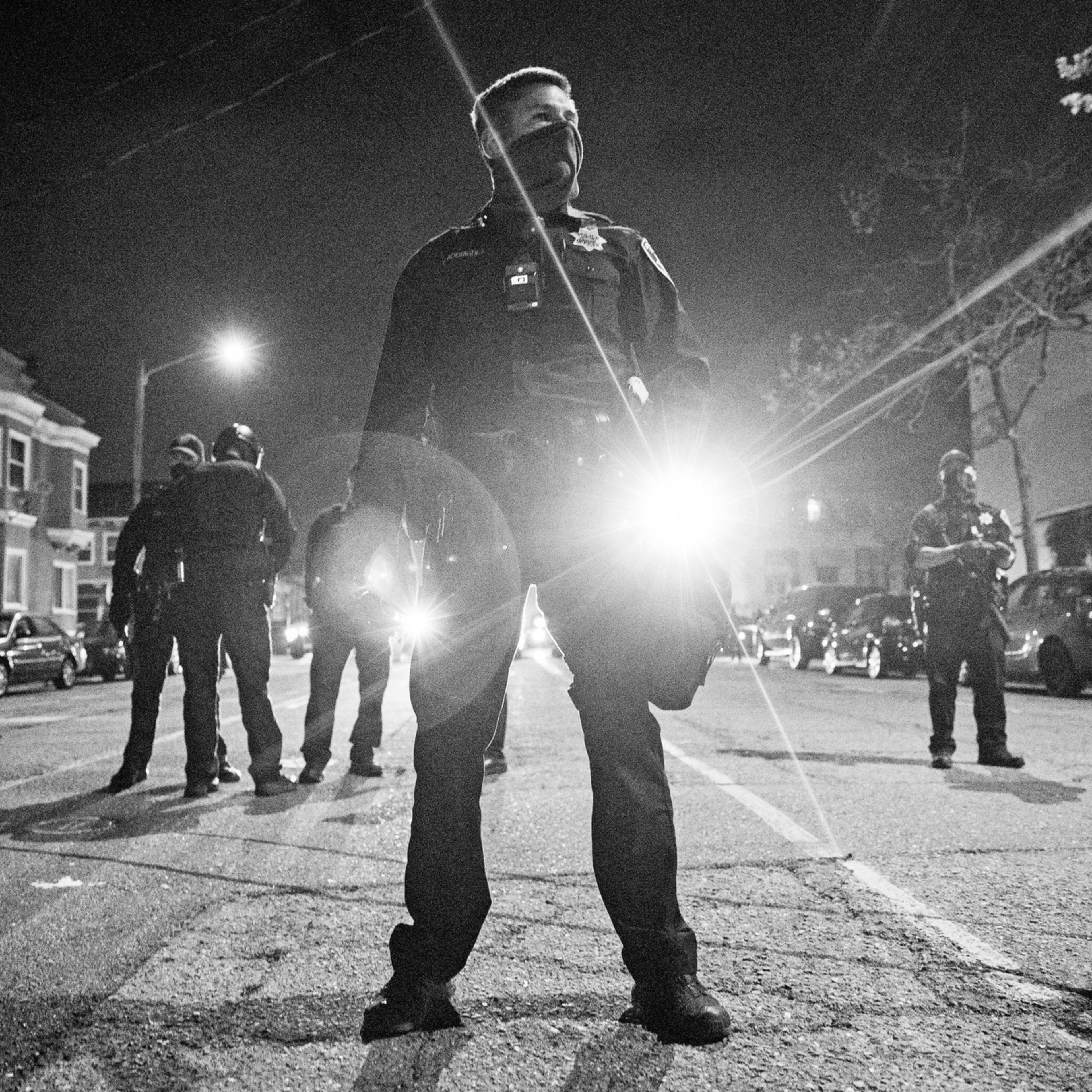

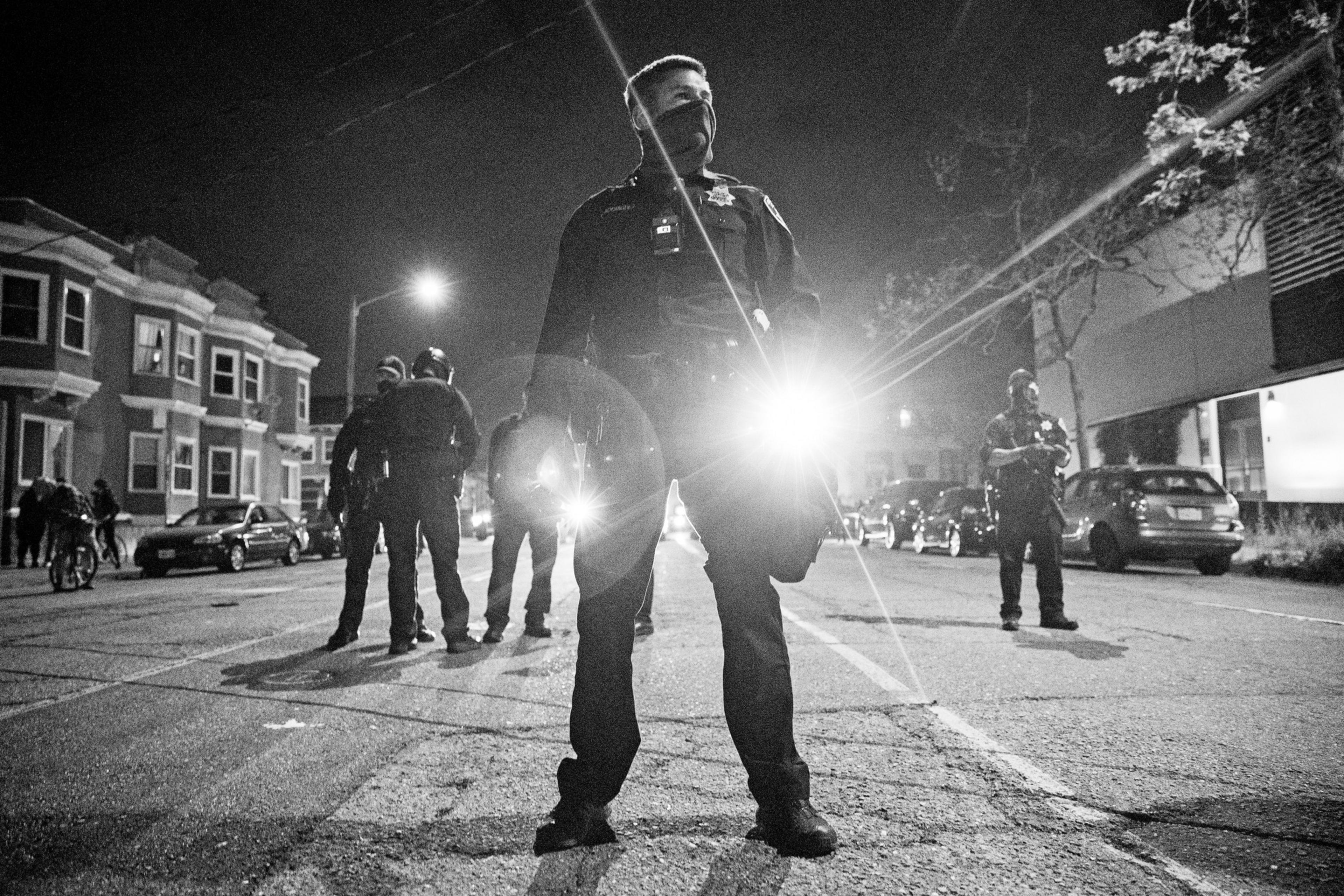

Poor records and technology infrastructure are just the tip of the iceberg. In the past decade, policy changes and decisions have upended policing in Oakland. These include reducing police stops (opens in new tab) by about 80%, limiting criminal pursuits, intensifying oversight, limiting crowd control (opens in new tab) and closing (opens in new tab) the jail. In parallel, the city reduced police staffing to the minimum required by law (opens in new tab) and may go further.

We’ve made these changes like an uncontrolled clinical trial, using Oakland residents as guinea pigs — except this “trial” has no principled design, no measurement of outcomes and no guardrails to ensure the experiment does not harm. In 2020, a small but prescient group of individuals foresaw this; they implored (opens in new tab) the Reimagining Public Safety Task Force not to replace proven policing methods without proving that alternatives will work.

It’s clear the experiment is not working. The state of lawlessness is so severe that Oakland has become a destination for crime tourism.

Adding to the pain, OPD has been under a federal monitor’s control for more than two decades — the longest federal oversight of any police department in the country (opens in new tab). Its 50-plus requirements have fundamentally reshaped operations. Officers are constantly scrutinized by the monitor, an investigator general, a police commission, a review agency, a media machine, a public primed to expect misconduct and those who may profit from maintaining the public perception of misconduct.

The department was about three months from ending its oversight when Mayor Sheng Thao fired Chief LeRonne Armstrong (opens in new tab) in February 2023. Subsequently, an independent arbiter cleared the chief of wrongdoing, (opens in new tab) but the oversight continues.

Many in the city believe in hopeful theories about police and criminal justice reform — theories based on nice-sounding labels like “violence prevention” and “police alternatives” or on shame-inducing phrases like “mass incarceration” and “police militarization.” But these are words, not data, evidence or rigor.

Oakland’s Department of Violence Prevention (previously called “Oakland Unite”) has produced only one report (opens in new tab) on its efficacy in its 20-year history. It showed that the department’s practices didn’t reduce arrests or victimization of program participants. Yet the city has generously expanded its funding (opens in new tab) since then, without any demand for performance accountability (opens in new tab).

Supporters argue that these alternative policing programs better serve the communities most hurt by the criminal justice system. But this disregards the impact of unchecked crime on those same communities. Analyses in 2013 (opens in new tab) and 2017 (opens in new tab) found that 67% to 78% of Oakland’s homicide victims are Black. The city’s surveys (opens in new tab) show that Black residents, those most severely affected by crime, prioritize policing and police data transparency more than any other demographic.

Certainly, deep, inscrutable sociological factors contributing to crime deserve to be addressed with public action. But those factors aren’t unique to Oakland, where the crime problem is much worse than that of nearly any other U.S. city, because we don’t enforce the law.

It’s a choice we made. We voted for the leaders and ballot measures that facilitated gaps in law enforcement for criminals to exploit.

We can have a safer Oakland, but we have to choose it.

Tim Gardner is a biomedical engineer and life science executive who co-founded Oakland Report (opens in new tab), which provides critical analysis of governance.